How Digital Nomadism is Disrupting Nation-States

How the Internet is disrupting nation-states, part 1/X

Note: this is part 1 of a series on how the Internet and globalization are disrupting nation-states.

Here are the fourteen articles in the series:

How the Internet makes Governments Impotent to Tackle Bottlenecks

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 1 of 2

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 2 of 2

Digital Shadows: How the Internet Empowers Anonymity and Challenges Governments

How the Internet prevents governments from enforcing their laws

Where it hurts most: how the Internet makes it harder for governments to collect taxes

The Web of Fraud: How the Internet Exposes Nation-States' Weaknesses

Having established universal historical principles in the previous two articles, we are now starting a series of articles on the major disruptions that the Internet (and modern means of transport) are causing to nation-states.

Later on, we'll use these historical principles and disruptions as the basis for a broad prediction of the behavior that nation-states will adopt, or are already adopting, to defend themselves.

So let’s start, shall we ?

Modern nation-states were created with an underlying principle that was never really thought through, because until very recently in history it was a given:

The immobility of their population

Indeed, until very recently, the overwhelming majority of the population travelled very little : a person with luggage travelling on foot walked around 75 to 100 kilometers (46 to 62 miles) a week, a traveller on horseback with light luggage could travel 200 to 300 kilometers (124 to 186 miles) a week , during the good season: winter was often impassable.

By stagecoach, Paris-Lyon around 1760 took 5 or 6 days, on one of France's best routes (today it takes 2 hours by TGV, the French high-speed train), Paris-Marseille took at least 9 days (3h10 today by TGV), Paris-Strasbourg 6 days (1h45 by TGV) and Paris-Bordeaux 8 days1 (with part of the route on a boat, 2h10 by TGV).

In the US, in 1786 it took up to 6 days to travel by stage from Boston to New York2 (while today it takes about 4 hours and 18 minutes by Amtrak train). In 1858, it took around 25 days to travel from Saint Louis, Missouri to San Francisco, California, by express stagecoach service3 (today it takes around 6 hours by air - with a stopover flight).

That's how long we could travel in the best conditions.

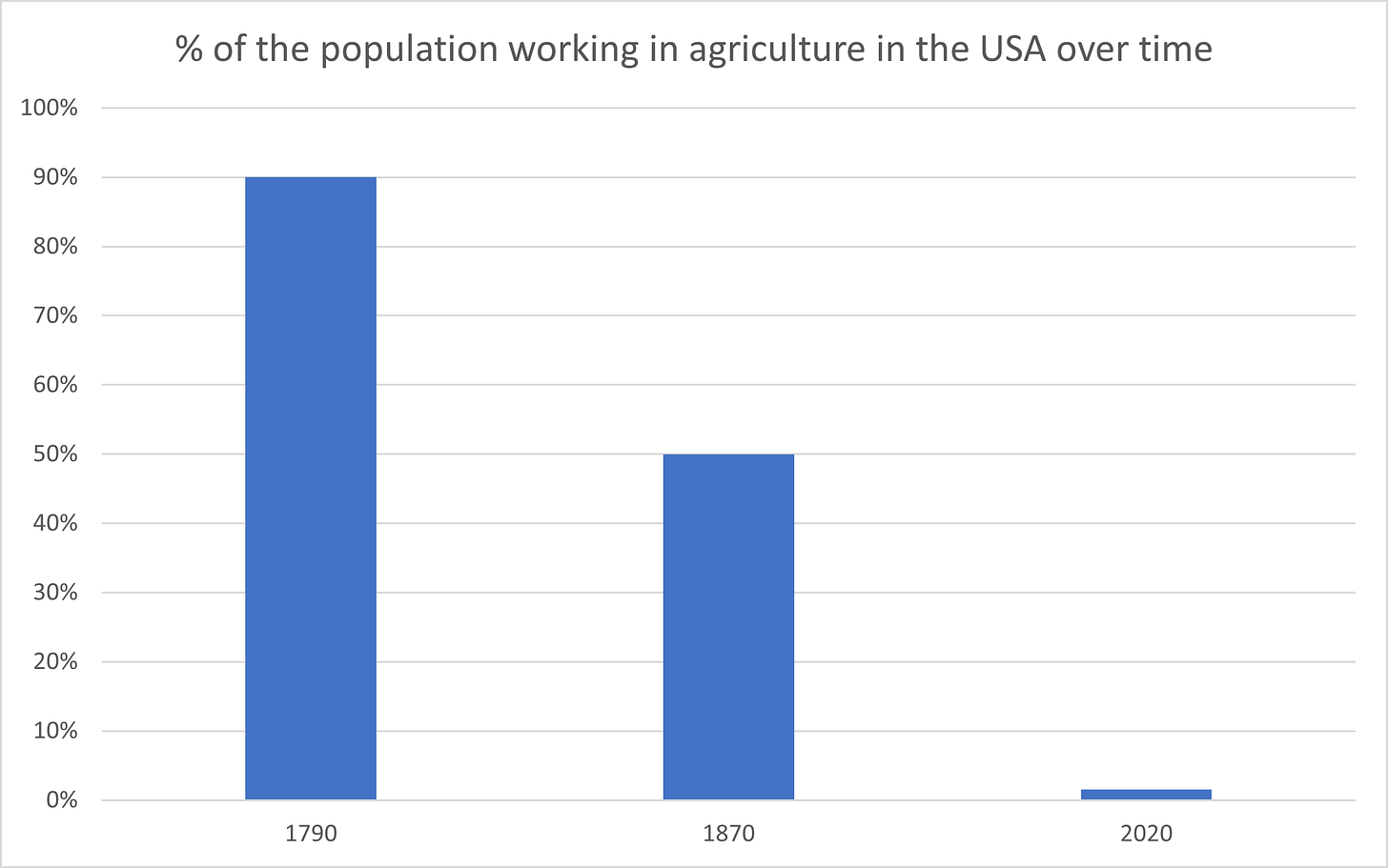

And the overwhelming majority of people were farmers, and attached to their land: in the USA alone, 90% of the population worked in this sector in 1790... compared with 50% in 1870, and less than 2% today4 . In 1856, when the industrial revolution was already well underway, half the population worked in agriculture in France and Belgium5 .

In those days, most farmers went to the nearest town fair perhaps once a year, a trip lasting one or two days at most.

This had many implications:

Governments knew that it was difficult for people to settle elsewhere, that they were tied to the land in one way or another.

Even if really difficult conditions could make them leave, there was a huge friction: you had to abandon most of your possessions, and make a long, difficult, dangerous and exhausting journey, to an unknown destination that had no guarantee of being any better.

Even the very rich weren't necessarily very mobile, as much of their wealth was tied up in land, which was difficult to administer from a distance.

For entrepreneurs, to do business in a country, you had to live in that country:

The company's employees absolutely had to be in this country.6

Virtually all the company's customers came from the same country

Communications were limited:

Local news circulated faster than distant news, fostering a strong local cultural identity.

The exchange of knowledge and ideas was also restricted, limiting technological advances and cultural innovations to specific regions.

National and regional identities were stronger:

Lack of mobility meant that individuals interacted mainly with people from the same region or country, reinforcing local identities and cultures.

Immobilism has also contributed to stronger national ideologies and stronger feelings of belonging to a homeland.

The tyranny of location

In short, almost everyone was subject to the tyranny of location: where you lived largely determined where you did your job or business, who you worked with, the laws that governed you, what was your particular national allegiance, and the level of taxes you had to pay.

Since then, of course, modern means of transport have made the world much more accessible, and today's means of communication enable ideas to be exchanged at the speed of light on a global scale.

This is already very disruptive for nation-states, but there is a recent trend in history that is even more disruptive...

How remote work disrupts this foundation

COVID has accelerated many trends in the use of digital tools and the societal changes they create.

The most obvious is remote work :

The number of job vacancies offering remote or hybrid working stabilizes at a new norm mid-2023 of 3 to 5 times higher than before COVID in the 5 English-speaking Western countries7

The increase in the number of people teleworking in the USA rose by 1.5% from 2013 to early 2020, just before the pandemic. The increase between the pre-pandemic level and 2021/2022 was 23%, after the containment peak had passed.8

Is this a temporary effect due to COVID, which will soon return to its previous level? We can estimate this by comparing it with e-commerce, which has also seen a huge boost, out of necessity. It is now back on its pre-pandemic trend, while remote working is 5x higher.

7.9% of 39,021 employees surveyed in 34 countries declared in April and May 2023 that they worked completely remotely. 25.6% work at least partially remotely9 .

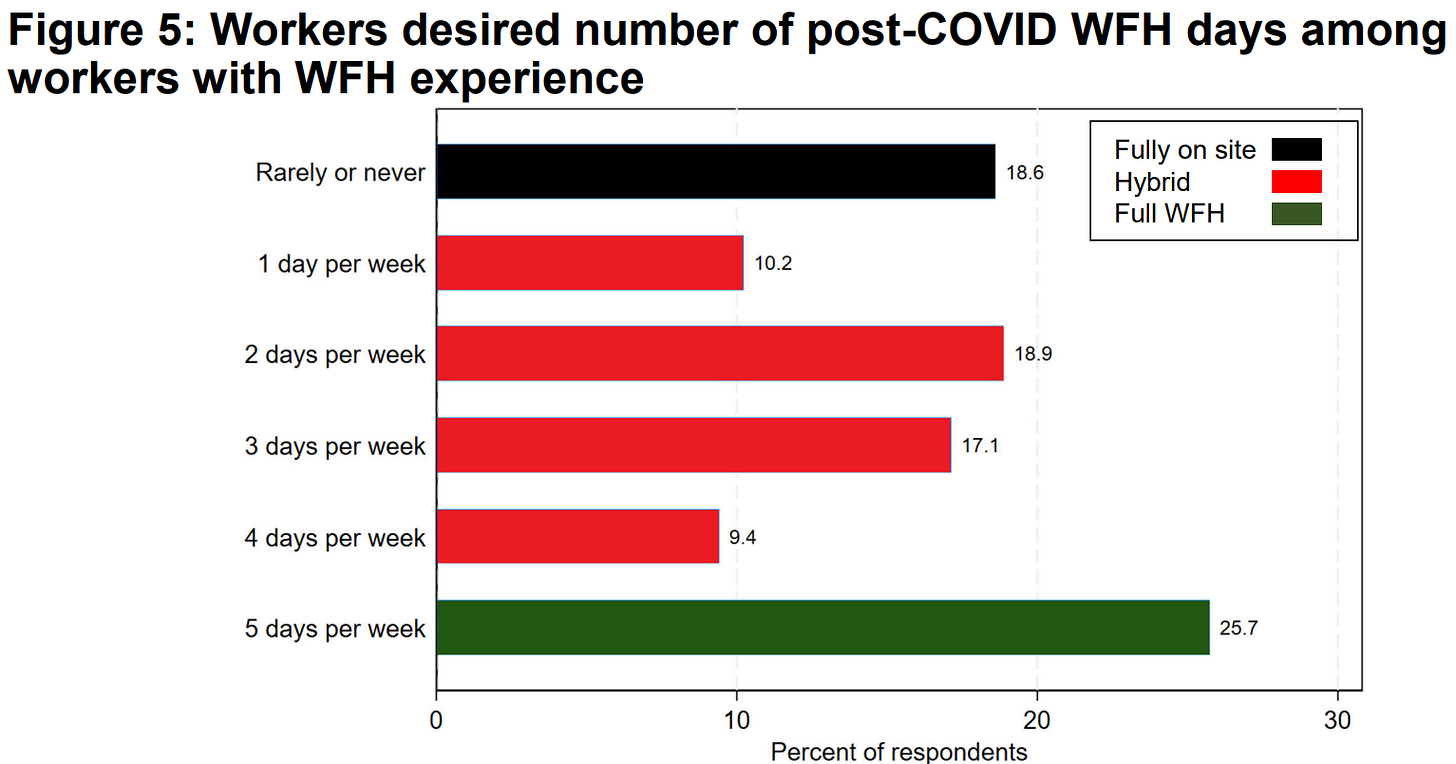

25.7% of 19,248 employees surveyed in April and May 2023 who experienced remote work during COVID say they would like to continue working completely remotely after COVID, the most popular response by far10 . This is followed by :

Rarely or never: 18.6%

Hybrid remote working: 55.6%, of which :

1 to 2 days a week: 10.2

2 days a week: 18.9%

3 days a week: 17.1

4 days a week: 9.4

So once they've had a taste of it, the vast majority of people prefer remote working, at least in part.

This includes highly sought-after talents, for whom companies are prepared to bend over backwards: they are obliged to accommodate their desires, because if they don't, it's the companies who will, who will get the skills from these talents.

This opens up a Pandora's box of possibilities for others, who will find it easier to apply for at least hybrid remote working, if only because of social pressure: "If Michael can work remotely, why can't I?”.

In short, remote working is here to stay.

The blind spot about remote work

And yet, when we talk about telecommuting and the possibility of doing a job completely remotely, most people think "great, I'll finally be able to go and live in the countryside, or in that little corner of the country that appeals to me, instead of that big polluted city".

A clear disruption for big cities

Of course, this is already very disruptive for nation-states as such: as there are fewer reasons to live in cities, and to have large offices in cities, this will reduce the real estate value of both offices and residences, make some public transport disproportionate to the new needs, and also make city shops less dynamic.

For example, it was estimated in early 2023 that San Francisco, one of the cities most affected by telecommuting11 , had 25 million square feet of commercial space vacant, that workers were spending around $3,567 less per year each on entertainment, dining and shopping near their workplace, for a loss of annual spending for San Francisco's entire residential and suburban workforce that could reach $2.9 billion12, the main reason cited being a 34.7% reduction in its on-site workforce13.

But an even bigger disruption is on the way

But most don't take into account a factor that is profoundly disruptive for nation-states: if you can do a job completely remotely, you no longer need to be in the country where your company is located.

If you can do a job completely remotely, you no longer need

to be in the country where your company is located.

This means that teleworkers can freely choose where to live, from hundreds of different jurisdictions.

And even if you have to stay close to the time zone where your company is located, for example because you have a lot of meetings or phone calls to make, it still opens up huge opportunities for choice.

If you need to stay within a time zone of plus or minus 3 hours from your company's country:

If your business is in France or Western Europe, this allows you to choose where to live from 99 different jurisdictions, including, as a European citizen, the 27 EU countries for which there is little or no paperwork to set up.

If your business is on the East Coast of the USA or Canada, then you can live in 37 different jurisdictions, not counting the internal jurisdictions represented by the American, Mexican and Brazilian states and the Canadian provinces (116).

If your business is on the West Coast of the USA, then you can live in 12 jurisdictions14.

This varies according to the range of time zones you're prepared to accept, and where you live.

Imagine being able to choose between dozens of different jurisdictions, not only for their quality of life and the language you can learn or improve, but also for the taxes you pay.

Imagine that anyone working entirely on a computer today has no obligation to be physically present wherever the company is located.

This suddenly gives the middle classes concerned the same flexibility to change jurisdiction that the richest have enjoyed for decades.

Imagine if just a small fraction of these people decided to move to another country, in particular to one where life is cheaper and taxes more lenient.

You're going to say, "Okay, but to be able to do that, you have to work completely remotely, and people who work completely remotely represent a minority today, so it's not that disruptive, is it?"

Great point!

You see, in every country, the richest and most mobile segments of the population contribute disproportionately to taxes: for example, in the USA, the richest 10% pay 73.7% of total federal taxes15 , in Canada, the richest 20% pay 64.4% of income tax,16 in Great Britain, the top 10% of taxpayers contribute 60.3% of income tax revenue17 , and in France, 10.76% of tax households pay 70.42% of income tax18.

And that's not counting corporation tax and taxes generated by jobs (for those who are entrepreneurs, probably many in this bracket), and VAT or sales taxes (the richer you are, the more you tend to spend and therefore pay VAT/sales taxes).

Pareto's law being what it is, these results are likely to be found in a good number of countries.

All it takes is for a small proportion of a country's wealthiest 10% to decide to move abroad, and the country's finances become seriously unbalanced.

What's more, it is estimated19 that, on average in EU countries, up to a third of jobs can be done completely remotely, rising to 37% in the USA - with these jobs accounting for 45% of total wages, given that they involve higher-than-average earners.

One study20 estimates the loss of income for Great Britain at £3.8 billion in income tax and £2.7 billion in social security contributions (a total loss of £6.5 billion in annual income, an optimistic scenario which assumes that only 10% of employees who can work remotely will move abroad), or £9.6 billion loss of income tax and £6.7 billion loss of social security contributions (total annual loss of £16.3 billion, with 25% going abroad) or £19 billion loss of income tax and £13 billion loss of social security contributions (total annual loss of £32 billion, with half going abroad).

And this estimate does not take into account the indirect loss linked to all the expenses these people will no longer make in their country of origin, and the other direct or indirect taxes they would have paid, such as VAT.

Can you see how profoundly disruptive this is for nation-states?

The growing number of visas for digital nomads (and the tax breaks that go with them)

And that's not all: more and more states have noticed the growing number of traveling remote workers - also known as Digital Nomads - and have set up specific schemes to attract them, often combining an easy-to-obtain visa with very attractive tax benefits.

In fact, at the time of writing, 46 countries offer a visa that is generally very easy to obtain, and - often - with advantageous tax conditions to attract entrepreneurs and employees who have been geographically liberated

by the Internet, and a further 12 countries have declared that they will be introducing this type of visa in the near future21 .

Here are a few examples:

In the Caribbean

Do you dream of spending some time on a tropical island paradise? Many countries in this region welcome you with open arms and offer highly advantageous tax conditions, including :

Antigua: digital nomad visa for 24 months

Income to prove: $50,000 per year

Taxes: 0% in most situations of a digital nomad. If you run your business from Antigua, 25% corporation tax, no income tax.

Grenada: digital nomad visa entitles you to live there for 12 months, renewable.

Proven income: $37,000 per year

Taxes: 0%.

In the European Union

(note that if you are already a citizen of an EU country, you don't need a visa to live in one of these countries. But you can often take advantage of the tax benefits outlined below):

Portugal: D7 visa valid for 1 year, renewable every year for 5 years, after which you are eligible for permanent residence.

Income to prove: €600 per month

Taxes: you can take advantage of NHR (Non Habitual Resident) status, which gives you 0% tax on income from outside Portugal, and 20% tax on certain income from within Portugal.

Spain: digital nomad visa valid for 12 months and renewable

Income to prove: twice the minimum wage, i.e., at the time of writing, €2,100 per month.

Taxes: reduced tax rate of 15% for the first four years, provided income is less than €600,000 a year

Croatia: digital nomad visa valid for one year, renewable 6 months after departure.

Income to prove: €2,232 per month, +10% per family member/partner

Taxes: 0%.

Czech Republic: digital nomad visa valid for one year, renewable

Income to prove: just €5,587 in the bank per person

Taxes: €70 per month

In the Americas

Costa Rica: 2-year visa for digital nomads

Income to prove: $2,500 per month, or put $60,000 in a Costa Rican bank

Taxes: 0%.

Ecuador: 2-year visa for digital nomads

Income to prove: $1275 per month

Taxes: 0%.

Mexico: temporary resident visa valid for one year, renewable for a further 3 years.

Income to prove: $1,620 per month, or $27,000 in a bank account

Taxes: 0% in most situations (unless more than 50% of your income comes from customers located in Mexico).

In Africa

Mauritius: another tropical paradise, easily accessible with their 1-year renewable visa for digital nomads.

Income to prove: $1,500 per month

Taxes: 0% if you spend less than 6 months a year in the country for all income not deposited in a Mauritian bank account. 15% corporation tax, and 15% income tax otherwise.

Seychelles: another tropical paradise island, offering a very easy-to-obtain visa (everything is done online), valid for 12 months and renewable.

Income to prove: unspecified, except that it must be regular

Taxes: 0%.

In Asia & the Middle East

Malaysia: digital nomad visa valid for 12 months and renewable 1 time

Income to prove: $24,000 per year

Tax: 0% in most cases (30% for income from work done for clients or companies in Malaysia)

Dubai: one-year renewable visa for digital nomads

Income to prove: €5,000 per month

Taxes: 0% in most situations for a digital nomad. If you run your business from Dubai, 9% corporation tax, no income tax.

I could have gone on like this for a long time: I've just made a small selection, focusing on countries offering easy visas and little or no taxation.

Because yes, often, as a digital nomad living in one of these countries, you pay less tax than a long-term resident or citizen of that country! We'll talk more about this schizophrenia and what causes it later in future articles.

It should be noted, however, that if you're American, it's a lot less straightforward because, as we saw in The FATCA disaster, you have the incredible good fortune to be a citizen of one of the very few countries in the world that taxes people on their citizenship (the other is Eritrea): wherever you go, you're going to have to declare your income to the IRS, and pay taxes on sums earned in excess of the “Foreign Earned Income Exclusion” which, at the time of writing, is any sum earned in excess of $112,000. Note that if your income is below or close to this amount, you can still take advantage of the tax breaks offered here. Obviously, you should consult a lawyer before doing anything :)

Note, however, that Americans can still make the most of their mobility, firstly by choosing freely among all the states in which to live (and the latest data show a clear trend for affluent people to move from high-tax states like California or New York to states with no local taxes, like Florida or Texas), or by moving to "quantum" territories, i.e. both in the USA without being in it, like Puerto Rico22.

This comes from the 1st principle we saw in “10 Principles of History for predicting the future”, “The power of governments is based on the immobility of their subjects”. As the mobility of the population increases, more and more countries will be tempted to introduce these kinds of restrictions, as we saw in “A Tax on your Nationality : can your country pull it off ?”

As you can see from this far-from-exhaustive list, you have access to some incredible, dreamlike countries, often offering a mix of exoticism, white-sand beaches, delicious food, historic sites and extremely low taxes.

Note also that it's not at all compulsory to use these digital nomad visas: if you want to stay longer in the country, you can quite happily obtain a more traditional visa - for example, many countries offer long-term residency to entrepreneurs who set up a business locally, and as I've already noted, EU citizens can go and live in any of the 27 EU countries without any paperwork.

Now, why would the person who works completely remotely choose to stay in his big, polluted, grey-sky city, or even in a beautiful corner of his own country, but overtaxed compared to an incredible, enticing and very lightly taxed part of the world?

What is the rational choice in this situation?

Can you see how profoundly disruptive this is for nation-states?

Depending on when you read this list, much of the information may no longer be up to date23 - the aim is just to give you an idea of the intensity of the competition, which has only just begun.

Yes, this is just the beginning: the competition is set to intensify. The 1st country to have introduced such a visa was Estonia, in August 2020, and three years later it's almost 50 countries doing so, a quarter of the world's countries.

In three years.

And the number of digital nomads is only increasing: although it's difficult to estimate because most digital nomads don't inform their country of their situation, in the USA alone, their estimated number has risen from 7.3 million in 2019 to 16.9 million in 202224 , and worldwide it's estimated at 35 million in 202325 .

Some projections (probably very optimistic!) put their number at one billion by 203526 .

In any case, one thing is clear: the trend is intensifying.

Here are a few case studies to illustrate the reality of the phenomenon... and the fact that it affects many professions

And this phenomenon affects many professions and many strata of society. To convince you, let me share a few concrete case studies: I've met all the people I'm going to tell you about here - with the exception of one, who is a public figure - although I've sometimes changed the names for confidentiality reasons.

1st case study: How Brian negotiated a completely remote job from the outset to move to Dubai

Brian is a Canadian I met by chance at a dance class in Dubai. The partner he'd come with, hearing that I was a completely geographically free web entrepreneur, connected us immediately and said we should have a chat.

And she was right: Brian's case is very interesting, and shows what more and more intelligent people are doing.

Brian is a logistics manager, a profession in which he can easily find work all over the world. After living in Canada and France, he was looking to travel a little more, and settle somewhere a little less tax-happy.

He came across an advertisement for a Greek boat delivery company, offering exactly the kind of job he wanted.

Problem: the company was considering a job with a traditional physical presence. But on further investigation, Brian discovered that the company required this prerequisite more out of tradition than obligation.

In fact, Brian could do all his work remotely.

And rather than being an employee, he had a brilliant idea: obtain Digital Nomad's visa in Dubai, and bill the Greek company from there.

It was a win-win deal: he found himself living in a very cool city, one of the best air hubs in the world, with a lot of flexibility to travel, and a tax rate of exactly 0.0%27 . His Greek company saves all employer contributions on his salary.

Of course, in return, Brian doesn't contribute to his pension, and has to take out private health insurance. This doesn't bother him at all: he's already lived in 2 different countries, so his hypothetical pension is already divided between them, and contributing to the Greek system doesn't appeal to him at all.

Even so, he doesn't trust the systems in most countries, and prefers to build up his own pension.

As for health insurance, he realized, like many people before him, that it's infinitely more advantageous to take out private insurance than to be forced to pay into a public system.

2nd case study : How Isabelle multiplied her income by 2 without increasing her salary

Isabelle, also Canadian, is number 3 in a 200-strong autonomous car company based in Quebec City.

Isabelle lived in Montreal (a 3-hour drive from Quebec City), so she was already working largely remotely before COVID, and completely during it.

She followed her boyfriend, who settled in Dubai, and started remote working from there, which is no easy feat, given the 8-hour time difference with Montreal!

But her company agreed, because Isabelle was the kind of profile you want to keep in your organization, and she proved within a few weeks that she could be just as productive.

At first, she kept her salary as an employee, which made it almost compulsory to pay Canadian taxes - Canada and the Emirates don't have a double taxation treaty - which didn't make much sense, given that she no longer benefited from Canada's infrastructure and services.

The next step was to change her status to freelance, and invoice the Canadian company from a structure in Dubai, which she did. This automatically doubled her purchasing power for the same salary, as she went from about 50% tax rate to zero.

A note on the talents of the people in these 2 case studies

You'll note that the two examples I've given are of people who have enough skills to be wooed.

This is one of my points: initially, it's mostly the smartest, most educated and most resourceful people who will negotiate a completely remote work job and take advantage of it to move to a jurisdiction that's more advantageous for them.

But this understanding will spread to all strata of society, and anyone who does their work completely on a computer will, one day, find themselves tempted to ask the two questions:

Do I want to keep coming into the office, or work completely remotely?

If I work completely remotely, where would I like to live?

And many entrepreneurs have been asking themselves this question for a long time, even in companies that I don't think were really designed for this purpose. Take Olivier Jacquemont, for example.

3rd case study : How Olivier went to live in a corner of paradise on the other side of the world

When Olivier Jacquemond set up Eurojob Consulting, specializing in the recruitment of Franco-German profiles, he didn't necessarily set out to live on a dream island on the other side of the world. But he quickly integrated new technologies into his infrastructure: his company has never had physical offices, and everyone works remotely.

He lived for several years in France and Germany, and it was when he discovered and fell in love with the Philippines in the early 2010s that the idea was born: if he was already working remotely from home in Europe, what was stopping him from working remotely from the Philippines?

So he got organized and went to live on the beautiful island of Palawan, surrounded by lush nature and next to superb deserted white sand beaches, while continuing to manage his French business via the Internet.

To cope with the 6-hour time difference between Paris and Manila, he held meetings in the afternoon (at home), and worked asynchronously the rest of the time.

At first, he kept up the same pace, working around 60 hours a week, but then he implemented a very simple hack that enabled him to immediately reduce his weekly online working time to 15 hours: he stopped his home Internet subscription.

Forced to travel 20 kilometers to get online in the big city nearby, he was forced to streamline his work, eliminate anything superfluous and... enjoy the unconnected life in his corner of paradise.

He has since sold his shares and still lives in the Philippines with his wife.

Of course, I've known many cases of fellow digital nomad entrepreneurs over the years, and the one I'd like to tell you about now is interesting because it shows just how much geographical freedom enables resourceful people in developing countries to go beyond the limits of their own country.

4th case study : How Kamal overcame the constraints of his native country with his Internet business

Kamal was a student in Morocco when he created his 1st blog, to help shy people overcome their shyness, which over time evolved into a love advice site for men and women - and a successful business.

If he'd had to stay in Morocco, Kamal would have been very limited in his growth potential: then as now, major payment processors like Stripe or Paypal don't work there, and Moroccans are very limited in their ability to send money abroad, which is problematic for paying for a lot of software essential to a web business.

Fortunately, he spent part of his studies in Warsaw, Poland, and fell in love with the city.

Well aware of the problems he would encounter if he set up his own business in Morocco, he set up a small company, in a light structure compatible with his student visa, in Poland.

When it started to work well, he turned it into a "real" business, and used it to obtain a visa, which to this day allows him to live in the city of his dreams.

He has since set up another fashion business, and has become a famous figure in the Polish capital.

The icing on the cake?

Kamal's blog is in French, so here we have an example of a Moroccan living in Poland thanks to a web company that sells mainly in France.

Another example of the Internet's profound disruption of nation-states - and the opportunities it offers for people who free themselves from the tyranny of geography.

Now let's talk about an entrepreneur at the head of a major French company.

5th case study : How Patrick Drahi runs a French company with revenues of 11.3 billion euros without being a French tax resident

This kind of set-up isn't just for small entrepreneurs: the big guys have been doing it for a long time, and the Internet has just democratized the process.

Let's take the example of one of France's best-known companies: SFR, one of the 4 incumbent mobile operators that brought cell phones and the Internet to the French.

Did you know that its CEO and owner, Patrick Drahi, has not been a French tax resident since 1999?

And he doesn't just own this illustrious company: in France, he is also the main shareholder in Altice and Numéricable (which merged with SFR to become Altice France), in BFM TV and RMC28, and was formerly the owner of Libération and l'Express.

His empire has made him one of the richest people in France, ranked 13th by Challenges magazine in 2023.

But he only appears in this ranking because he has French nationality, as he has not been a French tax resident for over 20 years: he settled in Switzerland in 1999, and a large part of his empire is based in other countries.

So much so, that in 2014, Arnaud Montebourg, then Minister for Productive Recovery, declared:

“There's a tax problem because Numericable has a holding company in Luxembourg, its company is listed on the Amsterdam stock exchange, [Patrick Drahi's] personal holding is in Guernsey in a tax haven owned by Her Majesty the Queen of England, and he himself is a Swiss resident. Mr. Drahi will have to repatriate all his possessions and assets to Paris, France. We have some tax questions for him29”.

Fleur Pellerin, then Minister Delegate for the Digital Economy, went even further a few days later: “If Patrick Drahi becomes the second largest telecoms operator in France, it would be logical for him to repatriate his tax residence to France and manage his business from Paris. [...] He will have to make an effort.”

Did Patrick Drahi, impressed by these thinly veiled threats from senior French politicians, immediately comply, and repatriate everything to France?

Well...

He didn't. He just went on with his life as if nothing had happened.

This hasn't stopped him from building a colossal empire in France and around the world.

So here we have an example of politicians stepping up to the plate... and doing so in the hope of bluffing, because in practice they are completely powerless in this situation.

This story is probably not unrelated to a change in French tax law, which in 2020 added a new condition for determining whether someone is a tax resident: any director of a French company with annual sales of over 250 million euros is automatically considered a French tax resident, regardless of his or her actual place of residence.

This is more symbolic than anything else, as it in no way affects Patrick Drahi: he is also a tax resident in Switzerland, and is protected by the tax treaty between France and Switzerland30, which takes precedence over national laws.

What's more, it's a safe bet that, in the event of a challenge before the European courts, this clause would be struck down as an obstacle to the free movement of people and capital within the European Union. It wouldn't be the first time (more on that later).

In fact, with his 5 nationalities31 , his residences all over the world, his frequent travels, and his companies all over the world, Patrick Drahi is an excellent example of an entrepreneur who has an international mindset, and knows how to use it to best effect.

Of course, given his means, Patrick Drahi could have done all this without the Internet, using technologies from, say, the 70s: airplanes, fax machines and telephones.

But that's precisely one of my points: Internet is the continuation of the disruption brought about by its new technologies, which at first was only accessible to the wealthiest - and the best advised - but which today makes it all accessible to the greatest number.

We'll see how you can do something similar, on your own scale.

6th case study : Philippe the psychologist

Philippe is an Australian psychologist I met in Bali. During COVID he was forced to do his therapeutic sessions remotely, and, like many others, didn't stop once COVID was over.

A keen traveler, it didn't take him long to add 2 and 2, and realize that he could now practice his profession remotely, provided he didn't stray too far from the Sydney time zone, where most of his patients are based.

This is what he did, moving part-time to Bali, which not only has an infinitely lower cost of living, beautiful beaches and nature, but is only 2 hours away from the city where he was working.

At the time I met him, he was considering taking advantage of one of the many visas that make it easy for people like him to settle in Indonesia for most of the year, leaving Australia and optimizing his tax situation. He was also beginning to prospect for fully online customers who were no longer located at all in his home base.

And many, many other cases

As a digital nomad, I meet so many similar people that I could share hundreds of case studies here, including by people who do aggressive tax optimization, for example Kevin, a freelance developer who has a "paper" tax residence in Hong Kong, obtained when he was a student, and a business in the UK at 0% tax if he doesn't invoice customers in that country (he doesn't), and who spends his time traveling wherever he wants, Patrick, a business lawyer registered with the Paris Bar, who lives in Dubai, helps many French people to settle there, consult with customers in France from Dubai, and returns to Paris when he has to litigate, Jean, who lives in Italy and has a company in Singapore with a manager who runs it from there, Stig, an athlete and holder of several Guinness records, officially a tax resident in Malaysia, but living just about everywhere, etc.

We'll have a chance to study some of these profiles (all real people) in more detail in the article on the 6 flags theories later, but note that there are probably already millions of people around the world who have organized their lives in a similar way, and their numbers are growing every year.

Does this apply to employees?

People who work remotely from another country while remaining employed will generally remain tax residents in the country of the company that employs them, even if they spend 0 days a year there: so they won't be able to take advantage of most of the tax benefits offered by other countries.

However, this can vary considerably depending on the tax laws of the company's country, and the tax treaty between that country and the digital nomad's country of residence: consult a lawyer specializing in tax law if you need to understand your particular situation.

But I also think that many employees in these circumstances will be tempted to change their status to that of freelancer (as we saw with the examples of Brian and Isabelle), in order to take advantage of these tax benefits, and also (often) because they no longer believe in their home country's ability to fund their retirement and health adequately (which is increasingly true, as we'll see in a future article).

And this goes hand in hand with a general trend that sees more and more people becoming freelancers, or trying their hand at it.

What about children?

I know hundreds of digital nomads, and many of them have children: I don't think this is a real obstacle (although it may be a limiting belief in many people's minds).

There are several reasons for this:

Being a digital nomad absolutely does not mean "traveling all the time". It means "no longer being subject to the tyranny of location, and being able to freely choose the jurisdiction with the best quality/price ratio in a market of jurisdictions fighting to attract you by offering you the best conditions".

Travelling all the time is a possibility offered by the fact of no longer needing to be somewhere, not an obligation.

So parents who want to offer their children a certain stability can simply choose to settle in the best jurisdiction at the moment, for the number of years they feel is right (it could be 10 years or more!).

Even moving country every 5 years (for example) is much less destabilizing for children, offering them extraordinary opportunities to discover new cultures, new environments and learn new languages.

It's an extraordinary opportunity for them to open their minds so early, to acquire languages so effortlessly, and to develop a multi-country mindset that will serve them so well in the 21st century.

It's worth many, many years of "classic" schools.

In fact, I think that offering your children the opportunity to acquire languages effortlessly is probably the best gift you can give them.

For example, a friend of mine, Michael, lives in Lisbon, he took on a British governess, and his children at 6 are trilingual: they speak French, Portuguese and English, and have had absolutely no impression of having made any effort to learn these 3 major languages, which they speak without an accent.

There is a growing trend towards homeschooling32, which fits in particularly well with the "real" nomadism of parents who would like to travel more often, especially as some countries like Germany, for example, prohibit it, on pain of fines or even prison sentences.

Getting out of the country solves the problem.

The ramifications of territorial detachment and the surprising parallels with communism

In conclusion, here we have an extremely disruptive element: if you manage to free yourself from the "tyranny of location" by being able to work entirely remotely, then you automatically have access to a market of jurisdictions that consider you as a customer, and therefore fight to offer you the best living conditions at the best price.

You then find yourself in a situation similar to someone who could only buy products or services from a single supplier - who therefore had little incentive to improve - to someone who suddenly has access to dozens of different suppliers who are fighting amongst themselves to attract and retain you - by offering the best products and services at the best price.

In fact, it's a similar situation to the people of Eastern Europe when their countries got rid of communism: they marveled at the choice of products they had access to, and their quality33 .

Such a contrast was even one of the influences that prompted Gorbachev to abandon communism and let the USSR dissolve: during a visit to Ontario, Canada, in 1983, he visited a small local supermarket, and was completely stunned by the quantity of products available and their apparent quality34 .

This episode was repeated by Boris Yeltsin, who visited a supermarket in Texas in 1989: he "walked the aisles [of the supermarket] shaking his head in amazement35" and "told the other Russians with him that if their people, who often have to queue for most goods, saw the conditions of American supermarkets, 'there would be a revolution'36 ."

It's likely that many of those who suddenly have access to the jurisdictional market will "shake their heads in amazement", at the very least - personally I'm still completely amazed - and that others will be somewhat unhappy at having to endure a monopoly situation just because they're stuck in one place.

As we shall see, there are already proposals and solutions for people stuck in one place: dissociate the territory from the laws that apply there. Yes, this already exists in many parts of the world, as we shall see.

Beyond this disruption directly affecting the wallets of States …

which is coming at the worst time in their history, as we'll see later, this disruption is also affecting the Nations that made up these states: as they become increasingly mobile, free of borders, connected to a global culture, more and more people will feel less and less attachment to their country of origin, while at the same time experiencing first-hand the much better value for money of governance services offered by other countries.

This will have consequences that we can predict from the 6th principle that history teaches us - people's obedience and motivation to follow someone's instructions come directly from the beliefs they hold in their heads.

How nation-states will respond

And just as politicians in Communist-ruled countries didn't want their people to realize the abundance of supply in capitalist countries, politicians today don't want their people to realize - for YOU to realize - that this jurisdictional market exists - while often rolling out the red carpet for foreigners who have understood the advantage of being treated as customers. We'll look at several examples of this paradox.

And just like the countries of Eastern Europe in their day, many governments will be strongly tempted to restrict their population's freedom of movement, trying to tie them to their territory to stem the hemorrhage - as we saw in the 1st principle of the 10 Principles of History for predicting the future.

And as we saw with the 9th principle - when a ruling power is disrupted, it doesn't surrender without a fight, even if the outcome of the fight is set by external conditions over which it has no power - and in “A Tax on your Nationality : can your country pull it off ?”, nation-states will struggle to stem the flow of its increasingly mobile population, trying to restrict its citizens' freedom of movement while they will increasingly make its choice in the market of jurisdictions.

This will be the subject of future articles.

2nd base disrupted: the Labor Code

In the meantime, we'll see in the next article how international remote working is already making the Labor Code obsolete, and how it's disrupting nation-states on another of their major pillars.

Stay tuned, and in the meantime, share in the comments: how do you think nation-states will react? And in the long term, which trend will win out, that of patriotism and restricted movement, or that of a large population of digital nomads choosing the best value jurisdiction for their needs?

“Roads and Travel in New England 1790-1840”, Roger N. Parks, 1967

“When Mailing a Letter to California Meant 25 Days in a Stagecoach”, Bob Doughty, 2008

"Employment by major industry sector", US Bureau of Labor Statistics

Our World In Data based on Herrendorf et al. (2014) and GGDC-10 (2015)

Or, in the rare case of cross-border commuters, in the country next door.

United States, Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, source: Work From Home Map

Working From Home data, 2023, via Nick Bloom, Stanford Professor of Economics

"Working from Home Around the Globe: 2023 Report, Cevat Giray Aksoy, 2023

Ditto

"San Francisco Is Losing Billions a Year in Local Spending to Remote Working", Liz Lindqwister, The San Francisco Standard, 2023

SWAA February 2023 Updates, Work From Home Research

All these calculations were made by the author using a fairly homemade method: I'll have to check them, but the figures give a good idea of the number of jurisdictions available. If you spot an error, let me know!

"Summary of the Latest Federal Income Tax Data, 2023 Update", Erica York, Tax Foundation

"Measuring the Distribution of Taxes in Canada: Do the Rich Pay Their "Fair Share"?", in "Towards a Better Understanding of Income Inequality in Canada", Charles Lammam, Hugh MacIntyre, and Milagros Palacios, Fraser Institute, 2017

"Tax statistics: an overview", House of Commons Library, British Parliament, 2023

"Statistiques: Qui paye l’impôt sur le revenu? Combien? Quelles inégalités selon les tranches de revenus", Guillaume Fonteneau, 2017

“The Impact of Digitalisation on Personal Income Taxes”, Rita de la Feria, British Tax Review, 2021

Ibid

"58 Countries With Digital Nomad Visas - The Ultimate List", Tracey Johnson, Nomad Girl, 2023

“Tax-Weary Americans Find Haven in Puerto Rico”, Frost Law

I recommend that you find out about the latest conditions before making any choice ! :)

"Number of digital nomads in the United States from 2019 to 2022", Statista, 2023

"Digital Nomad Statistics: How Big Is The Nomad Movement In 2023?", Two Ticket Anywhere

"Digital Nomads: Toward a Future Research Agenda", Nick Dreher & Anna Triandafyllidou, 2023

Back then. As I write this, there is now a 9% corporate tax in Dubai, with still 0% for income tax.

As well as a host of international companies, including the highly prestigious art auction house, Sotheby's

"Patrick Drahi, l'Ogre des Networks" by Elsa Bembaron

As paying tax in two countries would be unfair, and impossible in most cases, most countries have signed tax treaties with each other to avoid double taxation.

Patrick Drahi is Moroccan (because he was born in Casablanca), French (because his parents were), Portuguese (because he is descended from Jews who were expelled from Portugal in the 17th century, and therefore had the right to apply for Portuguese nationality in compensation), Israeli (because any Jew can apply for Israeli nationality, under the "law of return"), and has the passport of the Caribbean island of St Kitts & Nevis, which he obtained after investing in their economy. Nevis, which he obtained after investing in their economy.

“Homeschooling Statistics in 2023 – USA Data and Trends”, Jessica Kaminski, Brighterly, 2023

You can easily find on the Internet testimonials of reactions from Eastern Europeans when they discovered a capitalist supermarket for the 1st time, including East Germans. But here are a few links: Supermarchés et Communisme 1 - 2 - 3 - 4

"In 1983, Gorbachev took a stroll in small-town Ontario that helped shape the future of the Soviet Union", Toronto Today, Jamie Bradburn, 2022

"Boris Yeltsin's 1989 Visit To A Houston Grocery Store Is Now An Opera", Houston Matters, Michael Hagerty, 2020

Great and insightful piece of writing, thank you. Do you have any thoughts on how the increasingly widespread deployment of LLMs might affect nomads and nation states?

Olivier Merci pour ce super travail!!!! Tu aides tant de monde, ça fait du bien de lire ta lumière, elle nous dit que nous ne sommes ni seuls, ni fous à nous abasourdir et nous révolter de toute cette noirceur qui tente de nous engloutir et nous d'avancer péniblement à contre courant de cette masse soumise et aveuglée.

Et plus précieux que tout: tu nous offres des clés.

💓🙏🏽