How the Internet prevents governments from enforcing their laws

Unenforceable lawsuits, companies without headquarters, exiles, and the balance between the complexity of the case and resources

Note : this article is the 8th in a series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet.

Here are the fourteen articles in the series:

How the Internet makes Governments Impotent to Tackle Bottlenecks

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 1 of 2

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 2 of 2

Digital Shadows: How the Internet Empowers Anonymity and Challenges Governments

How the Internet prevents governments from enforcing their laws

Where it hurts most: how the Internet makes it harder for governments to collect taxes

The Web of Fraud: How the Internet Exposes Nation-States' Weaknesses

The power of governments, even democratic ones, comes first and foremost from physical force.

Because there are indeed many differences in the way laws are created, depending on the government: democratic laws must be passed by at least one assembly, which has been directly or indirectly elected by the people, while those in more authoritarian countries may have been chosen by a single man, or in any case a group that has not been elected in a truly democratic way.

But the way to enforce the law is the same everywhere: it comes from physical violence.

And that's normal, because there's a hierarchy between two types of laws that comes directly from the way the universe works:

There are the laws of physics

Then human laws

Millions of people break human laws every day - everyone has done it at least once - but no one has ever managed to break the laws of physics.

So states, to ensure that people respect their easily circumvented laws, must use inviolable laws, those of the very fabric of reality.

In other words, if you refuse to comply with a law, after a while (depending on the seriousness of the violation and the authorities' tolerance of it), someone with a gun will be sent to force you to comply.

And if you still refuse, the person with the gun is going to take you to prison (after an equally lengthy legal process).

And if you refuse to go along, that person will use physical force to make you do it, and in the worst case, may even kill you - legally if they use force in proportion to your resistance. And, of course, even some democratic states still use the death penalty.

You can try to turn the problem on its head: without the threat of physical violence, a state couldn't function - too many people would circumvent the law with impunity.

And it works all the better because most modern nation-states have a monopoly on physical violence: only they can legally use it to force people to do something on their territory.

This may seem obvious, but it's an innovation compared to the Middle Ages: the feudal era was characterized by physical violence that could be exercised by different actors on the same territory: the whole chain of lords, from the smallest vassal to the king, who owned the land, and the Church in certain cases, such as the fight against "heretics"1.

And this monopoly is rather a good thing: having several entities that can use violence on the same territory often leads to wars and insecurity, as in Mexico with the drug cartels waging a merciless war, between themselves and with the forces of law and order, which caused 128,000 violent deaths in this country between 2007 and 20202 .

In any case, it's a good thing when this monopoly is put to good use: to prevent criminals from taking control of society through fear (like the drug cartels) and to enforce fair and logical laws that take account of changing mores and culture3 .

How the Internet is disrupting this foundation

It's simple: a country's laws stop at its borders - because state officials armed with pistols only have a monopoly on physical violence within the borders of the state's own country.

If a policeman from country X tries to enforce the law of country X in country Y, the policemen of country Y will arrest him: you can put any country in the place of X and Y, it will still be the same: there can't be two different sources of violence in modern nation-states.

And the Internet knows no borders.

When a policeman tries to go international

In 2012, a senior police officer from Mauritius travelled to Geneva with a very specific objective: to interview two suspects in a bribery case.

Both agreed to meet the police officer, in the presence of their lawyer, and confessed.

So far, so good. But there's a small problem: the police officer, like the Mauritian judiciary, forgot to ask Switzerland for permission to conduct the investigation on their territory.

This was revealed a few years later when the trial took place in Mauritius: the Swiss authorities immediately launched an investigation, which resulted in the policeman being sentenced for "acts performed without rights for a foreign state", to "120 days' fine at 30 francs, suspended for two years, a fine of 720 francs and 500 francs in costs”4 .

A light sentence, probably due to the fact that the police officer did not use a weapon, that the two people responded voluntarily, and that they confessed to being guilty.

But it just goes to show you that states don't laugh when other states encroach on their territory.

However, someone using the Internet can use it to take action in country X, without actually being in country X, and therefore without being immediately visitable by country X officials armed with a gun.

This may seem obvious, but we shall see that it poses a considerable number of challenges for nation-states.

Example number 1: Twitter France sued for "refusal to respond to a requisition”

In 2021, two anonymous tweeters - one comparing the forces of law and order to Pétain's police force, the other describing the head of the prefecture as a "Nazi" who should be "hanged at the Liberation" - enraged the French administration to the point of asking the American company Twitter International for their identification data.

Twitter US refused to provide it.

As the French administration was unable to take legal action against Twitter in the United States (for reasons we'll see), it turned to Twitter France, and its CEO, for "refusal to respond to a requisition" and "complicity in public insult", using a classic "software" for administrations, which is to attack people and entities within the reach of its power, i.e. on its soil.

The administration claimed between 3,750 and 75,000 euros in damages from the CEO and Twitter France.

The court rejected the administration's case, for one simple reason: Twitter France is not responsible for content published on Twitter, it is merely a commercial antenna responsible for marketing advertising services5 .

The content manager is Twitter International in the United States.

This brought the French administration to a screeching halt: it would be costly and complicated for the French administration to to take legal action against the company in the United States, an investment it would probably have little incentive to make given the low damages sought (I'll come back in later articles to this very important point of balancing the motivation of the attackers and the complexity of the case).

As for attacking Twitter US in France, and trying to enforce the judgment in the U.S., that wouldn't work: a statute makes foreign defamation judgments unenforceable by U.S. courts, unless the foreign law offers at least as much protection as the U.S. First Amendment on free speech, or the defendant would have been found liable even if the case had been tried under U.S. law6.

And since France can't send its pistol-wielding agents to the U.S. to exercise the threat of physical violence that forms the basis of its power (because other pistol-wielding agents would arrest those French officials), there's not much it can do, short of blocking Twitter entirely, which would be circumventable and disproportionate.

So here we have an example of a company with enormous influence in a country, but which is very difficult for the country's justice system to reach.

Can you see how disruptive this is for nation-states?

It's the very first time in history that this has happened: previously, having influence in a place required having a physical presence there.

This is not to say that Twitter is completely untouchable: for other, more serious cases, certain actions could be envisaged, such as legal action in the country where the company is based, or judicial and police cooperation between the two countries.

But Twitter is safe about many things that it wouldn't be if it had a physical presence in every country where it has users.

Remember this:

As soon as you add a border, you add friction.

And remember the 5th principle on the relationship between attack and defense: with the Internet, it's much easier for an individual or a company to add a border (defense) than for a nation-state to break one (attack).

And just as the king during the Middle Ages could take any fortified castle but not 10, 20 or 30, no one is untouchable, but setting borders in your personal and professional organization is the equivalent of erecting walls, building a dungeon and digging a moat: all things being equal, administrations prefer to attack a less well-defended target.

Nation-states will therefore always prefer to attack a mono-country person rather than an international individual or entity, for the same offence. I'll come back to this point in detail in the article on the 6 flags.

Example number 2: a company with no physical location that defies regulators

Telegram

Telegram is a digital messaging service similar in operation to WhatsApp, which at the time of writing has over 500 million monthly active users.

Yes, half a billion people.

Such an influential company must have a duly registered headquarters that can be easily visited by any government authority, right?

Well... not really.

Telegram's physical location roughly follows the peregrinations of its founder Pavel Durov, who after leaving Russia in 2014 adopted the lifestyle of a nomadic entrepreneur, traveling with his team to San Francisco, New York, London, Paris, Berlin, and Finland.

"We pick a place and stay there for two or three months, then move on to the next place. Adiós7 ." he said in 2015.

He then moved to Dubai in 2017, but noted on his Twitter account in 2017, "We are currently based in Dubai, but we don't consider it our permanent base. It is unlikely that we will ever consider any location as our permanent base8 ."

And he does this largely to create confusion for governments, and make it difficult if not impossible for them to send him official requests9 .

Moreover, there's no physical address on their official website, apart from that of their company in the UK, designated as a data representative for the GDPR, and which is probably an empty shell.

In their FAQ, to the question "Where is Telegram based?", the site answers that the team is based in Dubai, and that "we are currently happy with Dubai, but are willing to move again if local regulations change."

Once again, we're talking about an application that is used by over half a billion people every month, and which deliberately plays on its lack of need for a physical location to thumb its nose at nation-states and make their job harder.

To convince you, I've included an excerpt from their FAQ:

"Cloud chat data is stored in multiple data centers around the globe that are controlled by different legal entities spread across different jurisdictions. The relevant decryption keys are split into parts and are never kept in the same place as the data they protect. As a result, several court orders from different jurisdictions are required to force us to give up any data.

Thanks to this structure, we can ensure that no single government or block of like-minded countries can intrude on people's privacy and freedom of expression. Telegram can be forced to give up data only if an issue is grave and universal enough to pass the scrutiny of several different legal systems around the world.

To this day, we have disclosed 0 bytes of user data to third parties, including governments.”

Can you see how this disrupts one of the fundamental foundations of nation-states and their governments? If identifiable physical locations are spread across enough different jurisdictions, can you see how this puts a spanner in their works?

And if there isn't even a physical location at all, where can governments send their requests and agents?

Example number 3: Exiles

In the past, when someone was causing trouble, a simple and relatively humane way to neutralize them was simply to banish them from the city or the country.

It was then much more difficult for this person to "foment his troubles".

This technique was widely used in ancient Greece (with the famous ostracism mechanism) and Rome10 for example, and worked very well... until technology got in the way.

After the invention of the printing press, it was quite possible for exiles to write books, safe from any repercussions, to have them printed in their country of exile, and to have them distributed under the cloak in their country of origin.

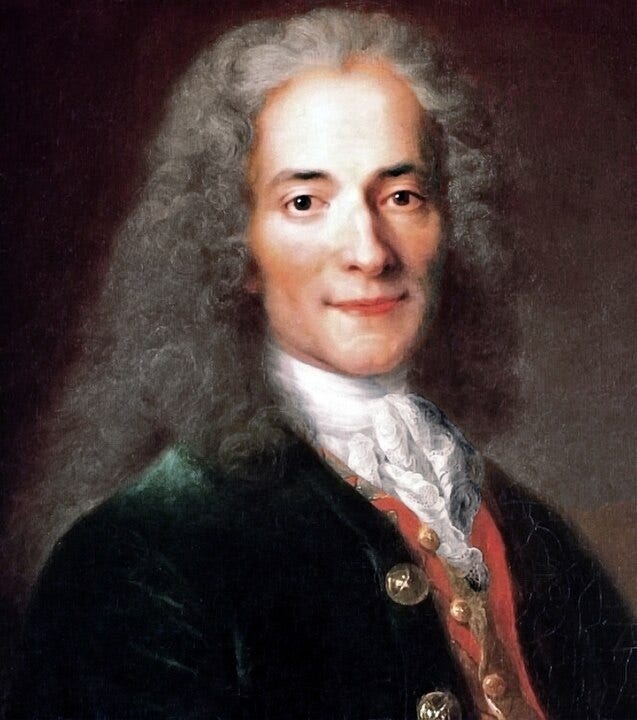

Voltaire

Voltaire, for example, was exiled many times, living in England from 1726 to 1728, where he wrote Les Lettres Philosophiques, a bestseller that was condemned by the French parliament to be "torn up and burned11 ", and in Switzerland from 1753 to 1758, where he wrote several books that were banned in France (yet sold very well there under the cloak), such as Essai sur les mœurs et l'esprit des nations, Diderot's Encyclopédie (which was banned several times by the French government, and even placed on the Index of banned books by the Pope), in which he wrote dozens of articles, and of course Candide.

It was possible, but there were still obstacles: you had to be sufficiently well known to gain access to a printer in the state that hosted you, then distribute the books clandestinely... and of course distributing books in states where they were banned put the distributors at risk.

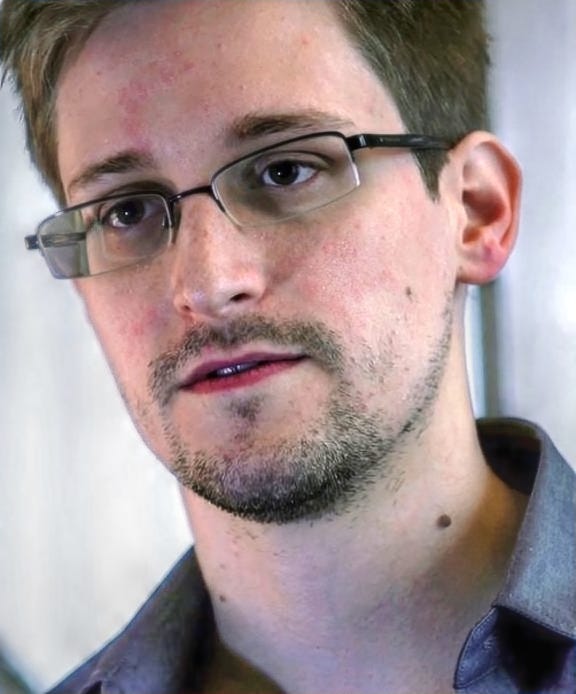

Edward Snowden

The Internet enables the same kind of avoidance mechanism, but with much less friction, risk and cost, and with a much wider potential reach.

For example, the notorious Edward Snowden worked for the CIA from 2006 to 2013. Outraged by the mass surveillance he saw there, particularly of American citizens - which went against the American constitution - he decided to reveal everything to the press, and stole over a million documents from the agency12 .

But he knew that if he just blurted it out and stayed at home, Snowden risked big, very big indeed: decades in prison, probably.

So he went ahead, and in May 2013 traveled to Hong Kong, from where he contacted several American and British journalists, who met him on the spot and obtained his documents, before publishing extracts of them in various famous newspapers, triggering a worldwide scandal.

The US government immediately filed a criminal complaint against Snowden, accusing him of 3 offenses each carrying a 10-year prison sentence, canceling his passport, and asking the Hong Kong authorities to extradite him - which they refused to do.

Russia then offered him political asylum, which Snowden accepted. He went there in June 2013, and is still living there at the time of writing.

And what's interesting in our case is that Snowden continues to have a huge influence on the United States and the world from his land of exile.

He has a Twitter account followed by over 5 million people (and is subscribed to just one account - that of the CIA13 ) his tweets and articles are regularly read by several hundred thousand people, he answers numerous interview requests which are seen by millions14 , and gives video lectures regularly - and can even physically walk around in some events, thanks to remote-controlled robots15 !

He also wrote a book, "Permanent Record", which immediately became a bestseller.

As soon as the book was published, the US government immediately filed a complaint, not to stop publication of the book - the 1st amendment to the US constitution forbids it - but for violation of the non-disclosure agreements in his contract with the CIA.

The judge ruled in favor of the U.S. government, giving it the right to seize all copyrights and remuneration to Snowden originating from U.S. soil and relating to the documents he stole.

Snowden had anticipated this, and had already received just over a million dollars for 56 video conferences, and an advance of 4.2 million dollars for his book. Of course, he refused to give them back - until he had a fair trial in the USA, he said16 - which enabled him to live comfortably for the rest of his life, and to devote himself fully to his mission, just as Voltaire's fortune17 enabled him to devote himself to his mission.

So here we have an example of an activist who is at the very top of the US government's most-wanted list, who lives safely in exile, and who continues to influence millions through the Internet - on a scale that would have been impossible for Voltaire and all the dissidents of the pre-Internet era.

And while Voltaire and many other "pre-Internet" activists were forcibly exiled, here we have an example of someone doing it voluntarily - knowing full well that the Internet will enable him to continue his work.

Because the Internet reverses the balance of power: exile is no longer necessarily a punishment, but perhaps a voluntary choice that allows you to reduce your risk in relation to a particular nation-state, while continuing to influence it.

Example number 4: A criminal offence... too insignificant to be prosecuted

An entrepreneurial friend of mine, whom we'll call Pierre, was in a difficult situation in the early 2010s: one of his team members, wound up after a heated discussion, used the admin credentials that Pierre had (a little too naively) shared to hack into Pierre's sites, replacing all content with a message essentially saying "My name is Pierre and I'm a scammer, shame on me"... and calling on his customers to report their supposed dissatisfaction.

It took Pierre several days to regain access to his sites, and the first thing he did when he restored service to his customers was to file a complaint. The offence was a serious one, punishable by 3 years' imprisonment and a €100,000 fine18 , and the person who had committed it was well known: far from hiding it, he had even claimed it on his website.

So it seemed that this case would be over in no time, and that the perpetrator would be heavily convicted.

But there were two problems, one of which was major.

1st problem: the author had admitted his crime on his website, using his real name, but it was necessary to establish the connection between this article and the real person and to identify his accomplices (whom he had mentioned without revealing their names), which required a (small) investigation. Not much to go on, given the severity of the offence, was it?

But that wasn't counting problem number 2: this person was living in Thailand at the time, as were the alleged accomplices.

I'll make it short: this simple fact created so much friction for the French justice system, that the investigation never took place, and the case was closed, even though it would very probably have led to a conviction if the suspect had lived in France, or in a more "accessible" country.

Pierre met the judge, who told him in substance: "You know sir, there are more serious things we have to deal with, like child abductions".

Because once again, as soon as you add a border, you add friction. And justice will often not even try to intervene if it considers that the ratio of "expected effect to energy expended" is unfavorable.

It has limited resources, and has to prioritize its actions.

This helps criminals, of course, but it also helps honest people who simply want to lessen the hold of states over them, as we'll see in detail in later articles. And in all cases, it diminishes the power of nation-states AND their prestige and legitimacy.

So, disgusted that the law could do nothing for him, despite all the taxes he paid, Pierre decided to move to a country with a pleasant climate AND low taxes. He is still there as I write these lines.

So here we have a concrete example of a nation-state - France - being prevented from providing the service it promises - justice - by the borderless nature of the Internet, and suffering a consequent loss of prestige and legitimacy in the eyes of the person seeking justice, who wondered in reaction: "Am I getting the best possible service for the price I'm paying?”

As this person was also a web entrepreneur, he was able to move easily as a result, finding - rather easily, it has to be said - a country where the value for money of the services offered by the government was better.

So we see a double disruption for nation-states: the Internet 1) makes the services they promise and which have made them indispensable increasingly difficult to deliver, thus eroding their prestige, and 2) facilitates the displacement - or flight - of those who no longer believe in their ability to fulfill their promises.

So the nation-states are under attack from all sides via the Internet. And this is just the beginning, as you are beginning to see.

Coming soon

In next week's article, we'll look at how the Internet lets you choose your own laws. Stay tuned, and in the meantime, click here to follow Disruptive Horizons on Twitter (and here on Nostr), and debate these topics with me, or just share the love :)

The series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet

This article is the 8th in a series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet.

Here are the first seven articles in the series:

"The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe 950-1250" R.I. Mooren, 1987, and "Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History" by Douglass C. North, 2009

"Organized Crime-related Homicides 2007-2016" Milenio, [REF A VERIFIER!!!] "Organized Crime and Violence in Mexico, Analysis Through 2018" Justice in Mexico, Department of Political Science & International Relations, University of San Diego, "GANG VIOLENCE IN MEXICO: 2018-2020", Goos, Curtis

When that's not the case, you don't have much choice but submission, revolt or exile - more on that later.

"Un policier mauricien mène l’enquête à Genève : condamné par le MPC", Gotham City, 2017

"Haine en ligne: Twitter France et son directeur général relaxés" , Libération, March 21th, 2022

This is the SPEECH Act (Securing the Protection of our Enduring and Established Constitutional Heritage), established in 2010.

"Lunch with the FT: Pavel Durov", John Thornhill, Financial Times, 2015

See footnote 7

Preface to the 1879 edition of Lettres Philosophiques, Beuchot

"Pentagon Says Snowden Took Most U.S. Secrets Ever: Rogers", Bloomberg, 2014

Edward Snowden on Twitter. We appreciate the nose-thumbing!

For example, interview 1368 with Joe Rogan, seen by nearly 40 million people (!)

See for example his TED talk, "Here's how we take back the Internet", 2014

By "fair trial", Snowden means in particular a fully public trial, rather than the standard at least partial closed-door hearing of espionage cases provided for by the Espionage Act of 1917. This law would also prevent him from presenting a defense based on the public interest. "Edward Snowden wants to come home: "I'm not asking for a pass. What I'm asking for is a fair trial" "

Created through judicious investment

Article 323-1 of the French Penal Code

Great piece as per usual!

However, want to point out one typical fallacy: "And this monopoly is rather a good thing: having several entities that can use violence on the same territory often leads to wars and insecurity, as in Mexico with the drug cartels waging a merciless war."

Monopolistic states can also lead to merciless war, see North Korea and the countless victims of inter-state war, and witness that states killed 163 million of their own people in the 20th century: https://www.owl232.net/papers/statistics.htm

You can't compare good statism with bad anarchy, you have to compare good statism with good anarchy (i.e. law and order persists, but it's not provided by the state), see e.g. work by David Friedman.