How the Internet makes Governments Impotent to Tackle Bottlenecks

The interesting examples of Napster, The Pirate Bay, porn sites, and how they inspired cryptocurrencies

Note : this article is the 3rd in a series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet.

Here are the fourteen articles in the series:

How the Internet makes Governments Impotent to Tackle Bottlenecks

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 1 of 2

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 2 of 2

Digital Shadows: How the Internet Empowers Anonymity and Challenges Governments

How the Internet prevents governments from enforcing their laws

Where it hurts most: how the Internet makes it harder for governments to collect taxes

The Web of Fraud: How the Internet Exposes Nation-States' Weaknesses

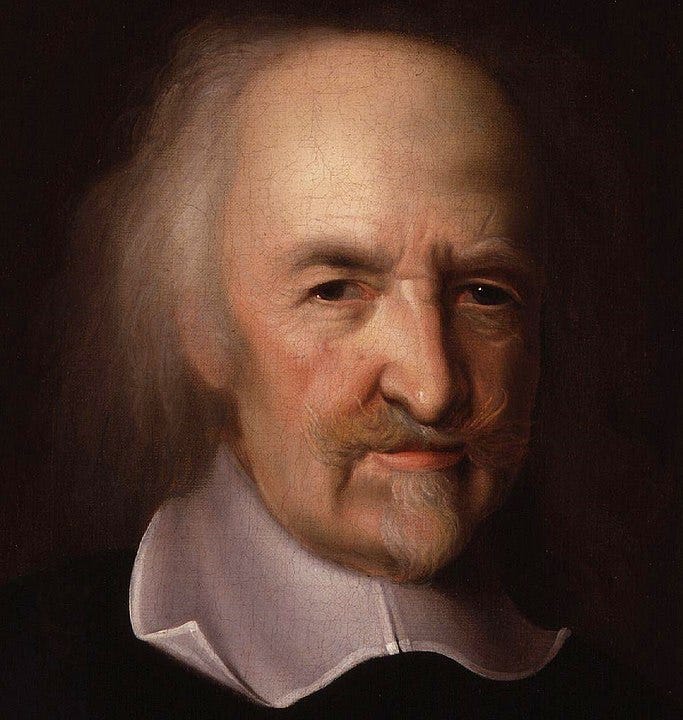

In the 17th century, Thomas Hobbes described the state as a giant, a Leviathan so powerful it could crush every individual with ease1 .

He was right, of course. But what he didn't make clear was that the state has a much harder time crushing a multitude: even it is quickly overwhelmed when enough people decide not to comply.

If, for example, 10% of a country's population stops following a law, it will be virtually impossible for the state to investigate and prosecute every single offender.

And at some point, it may even have to abandon this law, crumbling under the weight of "criminals", just as the United States had to do, when it was forced to abandon Prohibition just 13 years after introducing it, because the number of people who continued to drink alcohol was clogging up the entire American legal system, and feeding a massive criminal industry2 .

The preferred solution in these cases is always to tackle the bottlenecks: the points through which everyone has to pass, and/or the leaders who inspire the rest of the group.

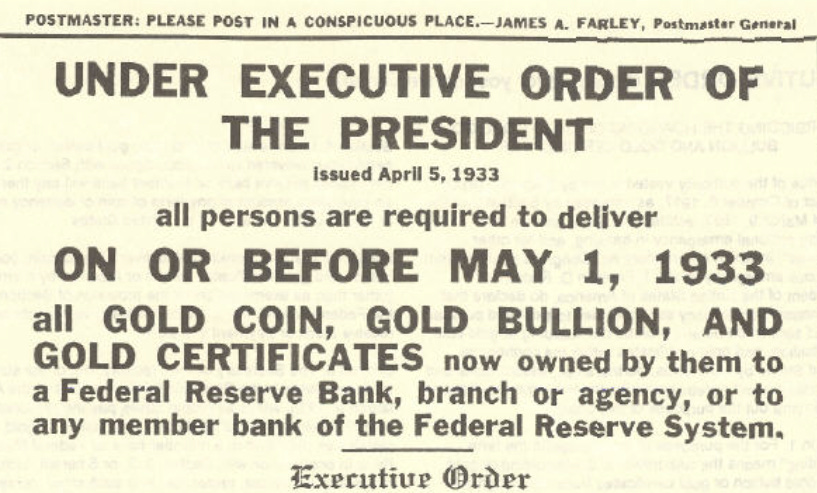

For example, when Roosevelt banned Americans from owning gold in 19343 , he didn't send the police to search every house for every hidden gold coin: that was mission impossible, even for the mighty American state.

Instead, he made it compulsory for everyone to sell their gold to the government at a set price [which was + or - the market price], forced banks to confiscate their customers' gold, and threatened anyone who didn't sell their gold with a fine and even jail time.

Keeping gold coins hidden under one's mattress thus became a criminal offence: the fine was high - twice the amount of gold seized - and the theoretical prison sentence a maximum of 10 years.

In theory, these penalties were a powerful deterrent.

And which "target" do you think was more likely to comply with government orders? The banks, or the public?

If you answered "the banks", you're right.

In fact, it is estimated that far less than half of all Americans holding gold obeyed the law. The rest hid their gold under the mattress, or sent it to neutral countries like Canada4 .

This just goes to show how difficult it is for the state to control the multitude, even when it's brandishing dissuasive prison sentences.

It's much better suited to controlling a few dozen well-identified and duly registered players.

How the Internet is disrupting this foundation

But the Internet is making it increasingly difficult to control bottlenecks, by giving the multitude the means to coordinate directly between millions of individuals, across hundreds of different jurisdictions.

Let's take a look at a few examples.

Example number 1: Napster and The Pirate Bay

In 1999, a software program was to create a revolution, profoundly changing the habits of an entire generation: for the 1st time, Napster made it easy for anyone to find music, from the most popular to the most obscure.

All you had to do was type in the name of the song, album or artist, and voilà! You could have the MP3 on your computer in a matter of moments. No more asking friends for it, hoping they've got it on tape somewhere.

The problem, of course, was that the company behind Napster hadn't taken copyright laws into account: as soon as it became known, it was beset by lawsuits, had to cease its service in 2001, and went bankrupt in 2002.

Here, the bottleneck was obvious: by making the company behind Napster disappear, we were making the service disappear, since everything passed through the company's servers.

However, no users were prosecuted (as it would have been too complicated to prosecute all the millions of users).

In 2001 (and partly as a reaction to what had happened with Napster), the Bittorrent protocol was created, which, like Napster, enabled files to be shared over the web, even illegally.

But there was one big difference with Napster: the company behind Bittorrent didn't offer any of the files, it just provided the protocol for exchange.

It was the users who then used the protocol legally or illegally, not the company itself, which was therefore unassailable.

The problem for users, however, was being able to find the "Torrent links" to the files they were looking for: a catalog, or search engine, dedicated to this was needed.

That's where the Swedish Piratbyrån group comes in, made up of activists whose mission is to promote the free sharing of information and culture.

They decided to create a search engine for Torrent links, which saw the light of day in September 2003: The Pirate Bay.

They didn’t offer the files directly (just like Napster at the time), but simply Torrent links that enable users to exchange files with each other using the external Bittorrent protocol (unlike Napster, which itself hosted the technology for exchanging files).

This is an important nuance, and the founders were confident that they would be protected from any legal attack thanks to it.

And indeed, for a few years this seemed to be the case, even as the site became immensely popular, entering the top 100 most-visited sites in the world5 ... until the police raided the site's Swedish host, seizing the servers, in 2006.

This didn't stop the site, which was offline for just 3 days, but it did give the Swedish courts enough to charge the founders with "promoting copyright infringement committed by others6 " (note that they were not directly accused of infringing copyright).

In 2009, the site's 4 creators were each sentenced to 1 year in prison and around 3.5 million US dollars in damages at first instance. The prison sentence was reduced on appeal, but the damages were increased.

This didn't stop the site: its code was made available as open source, so anyone can install it on a server and run it7 . And all you have to do is type "The Pirate Bay" into a search engine to realize that there are many copies out there today, making it easy to find million of films, songs and other intellectual creations shared illegally.

Some countries require their ISPs to block the site, but there are so many copies that it's usually quite easy to find an unblocked one (have fun trying for yourself).

Otherwise, using a VPN or Tor (which I'll talk about in a series of articles on computer security) is an easy way around the problem.

Why is it impossible for the authorities to stop The Pirate Bay?

Because, having attacked the centralized part of the site (the creators, who had not hidden themselves and were therefore identified), they found themselves at a loss when faced with the decentralized aspect of what remained: millions of users worldwide, and a site that anyone can easily copy.

Some countries, such as France, have implemented extensive surveillance of their entire national Internet in an attempt to punish end-users, but this has been largely unsuccessful, as we'll see a bit later in this article.

I know people who have been using The Pirate Bay since 2003, without any interruption in their use for all those years8, having simply started using a VPN from the moment The Pirate Bay was censored in their country, or Hadopi or an equivalent was put in place, which is good security practice anyway, as we'll see in later articles.

By 2022, Bittorrent accounts for almost 10% of all traffic sent (and not received) on the Internet, making it the number 1 protocol and service for sending data, and the 9th global service/application in terms of total volume of data exchanged9 .

This just goes to show how powerless governments are to curb a phenomenon that is clearly illegal when it is massive, decentralized and borderless.

Governments are powerless to curb a phenomenon, even clearly illegal,

when it is massive, decentralized and borderless.

Remember these words: massive, decentralized and borderless.

Any project that uses these characteristics has such a huge asymmetrical advantage against nation-states that it's almost certain to win against them as soon as it reaches a critical mass of users.

This is in line with the 5th principle to be learned from history we saw in “10 Principles of History for predicting the future” : A reversal of the balance of power between attack and defense technologies is highly disruptive to the powers that be.

And many others have also taken note of this point, not only to create similar sharing systems, such as the educational book-sharing site Z-Library, or the scientific article-sharing site Sci-Hub, but also to develop technologies incensurable by governments: many cryptocurrencies, as well as the DeFi apps and services which we will cover in future articles, have been inspired in part by this ongoing success of The Pirate Bay against all the world's governments.

And of course, this point was most likely noted by Bitcoin's creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, who ensured that the 1st cryptocurrency was decentralized, which therefore created a phenomenon... massive, decentralized and borderless.

And many crypto-currencies have followed in his footsteps.

Example number 2: Porn sites

The Internet has made porn extremely accessible, including to children, and restricting their access to these sites is a battle that many states are undertaking.

I invite you to watch this fight carefully in your own country, if it takes place, and observe the concrete results, because my prediction, given all the principles we've seen so far, is that states will lose it, short of instituting Internet censorship worthy of China.

Even making all pornographic sites illegal wouldn't work without extremely severe filtering, which would never be 100% effective and would have many side-effects, blocking sites on sex education or the fight against STDs, for example, as is already happening10.

And even effective blocking would just move porn onto P2P exchanges on the BitTorrent protocol or via the good old exchange on physical media like USB sticks: we're talking here about an industry that addresses one of the most primal and widespread needs of the human species, so there will always be a very strong demand, and historically when a government tries to suppress supply without suppressing demand, it fails almost every time when demand is strong, as we've seen with the example of the USA and prohibition, and as we'll see in future articles with the war on drugs.

Note again that I'm not saying this is good or bad: I'm simply describing the disruptions inflicted by the Internet on nation-states, and how they react to them.

One of the first countries to attempt this fight was the UK, which decided in 2017 to introduce an age verification system for accessing pornographic sites. The plan was simple: anyone wanting to access these sites would have to prove they were over 1811.

The problem, of course, was that just clicking on a button saying "yes, I'm 18" wasn't enough: the law made a verification system mandatory, but didn't specify which one.

After much deliberation, a number of different methods were validated, including validating credit cards, using a private third-party verifier (who swore up and down that no porn site consultation data would be associated with the ID they stored in their databases), or allowing people to buy a "porn pass" age verification document from a newsagent.

Websites that refused to comply with this policy risked being blocked by ISPs or having their access to payment services restricted.

Very quickly, the initiative met with fierce resistance from both content providers and civil liberties advocates12.

Few people were motivated by the idea of revealing their identity to perform one of the most intimate practices imaginable, and many users were quick to circumvent the restrictions with VPNs or by using lesser-known platforms, thus evading the law13.

In the end, the project was abandoned in 2019, not so much because of opposition, but because of the practical challenges involved in implementing such an Internet system.

This UK fiasco is yet another clear example of how incredibly difficult it is for nation-states to control a massive, decentralized and international phenomenon.

You'll note, however, that here, unlike in the case of The Pirate Bay, many of the players are not anonymous individuals, but companies, often large and multinational, duly registered and identified, which in theory makes them easier to reach.

But such companies with no physical presence in a country are extremely difficult to control in that country, and again, even success in doing so would just tip porn sharing onto P2P exchanges, which are absolutely uncontrollable without the equivalent of China's Great Firewall.

Think of the - probably - hundreds of people in the government who worked so hard on this bill, the thousands and thousands of hours of work invested in a complete waste, the taxpayers' money thrown out the window, only to give up before actually implementing what the law called for.

Look at the extent to which nation-states waste considerable resources trying to regulate a phenomenon that not only escapes them but disrupts them, and how this also undermines their legitimacy, by making them appear incompetent and airy-fairy.

Example number 3: Hadopi

At a time when illegal downloading of copyright-protected works was taking on unprecedented proportions (helped in no small part by The Pirate Bay), the French government wanted to find a solution to the problem, and the best minds in government turned their attention to the question of how to prevent John and Jane Doe from obtaining the latest summer hit, or the Hollywood blockbuster that had set cinemas ablaze a few months ago, free of charge and by morally reprehensible means.

After much reflection, the great minds decided on several measures:

Firstly, to transform "making protected works available to the public without the authorization of their rightful owners" into a simple contravention - which at the time was an offence punishable by a maximum fine of 300,000 euros and three years' imprisonment.

This arrangement was proposed because it was unrealistic to prosecute the millions of illegal content downloaders - so here we see that one option for states overwhelmed by the multitude is to reduce the severity of penalties, to make them more credible, which is already an admission of impotence in itself.

Introduce an administrative penalty specifically for "failure to monitor Internet access" - because it was extremely difficult for the authorities to prove who was the author of the illegal download. On the other hand, it is easy to prove who is the owner of the access used to make the download.

Enable rights holders to scan the Internet for French IPs among users of P2P networks such as Bittorrent14

Set up a "graduated response" system that :

Sends a warning email for every 1st infringement detected

Then a registered letter to 2nd

And finally, the suspension of Internet subscriptions after 3rd offences, without the need for legal proceedings.

Yes, you read that right: Hadopi wanted to cut off an offender's Internet access, even if it wasn't proven that he or she had initiated the illegal downloads.

This provision easily fell by the wayside when it was submitted to the French Constitutional Council, as Internet access was already considered a fundamental right in 2009.

It started badly: once the 2nd infringement had been recorded, Hadopi's only real power was to forward the pirate's file to the court so that it could impose a fine.

The 1st fine was imposed in 2012, at €15015 . Between the start of Hadopi in 2009, and 2015, the institute sent the incredible number of... 361 files to the various local courts of aggravated pirates.

It must be said that it was easy enough to get around Hadopi for anyone with a little knowledge:

Using a VPN immediately makes any illegal download invisible to Hadopi, provided the server to which the VPN connects is outside France. And if the server is in France, it's the server's host that will receive mail from the authorities, not the Internet user downloading.

Viewing pirate content via streaming, or live on pirate sites, is not detectable by Hadopi.

Even for those who don't know anything about it, they may be lucky and be among the millions of French people who have a shared IP with an ISP, which is used by several of the access provider's customers, making it impossible to identify the person behind the IP.

And sending a lot of cases to the public prosecutor's office would have the same effect as sending all the people who drank during Prohibition to the public prosecutor's office: it would completely clog up the judicial system and make it incapable of dealing with "serious" cases.

Given the lack of results, a Senate report in 2015 recommended "the abolition of the HADOPI, considering that this authority has not demonstrated its effectiveness as an Internet watchdog and that the means of combating piracy through the graduated response mechanism are ineffective16 ."

All in all, between 2009 and 2021 inclusive, Hadopi was :

13 million messages sent (it shows you the scale of the phenomenon)

Just over 7,000 cases referred to the public prosecutor's office

And... 517 cases decided

A total of 87,000 euros in fines...

With a budget of 82 million euros17

And for the following results:

The estimated number of people in France downloading illegally on P2P networks has fallen from 8.3 million in 2009, to 3 million in 2021. A victory, isn't it?

Well... not really: 8.3 million people watched pirated streaming content in 2021

And 5.6 million people download pirated content directly... every month

As Hadopi itself states in its 2021 report: "piracy still concerns 12.4 million Internet users every month [in France], all protocols combined18 ".

In short, we can safely say that Hadopi was a fiasco, serving no purpose other than to throw taxpayers' money out the window.

And why was Hadopi ineffective?

Quite simply because the legislator attacked a decentralized technology of the 21th century with a methodology of the 20th century, a methodology which deeply assumes a centralization of the target, which must have 1) a unique or main physical location and 2) a bottleneck.

Two things that aren't true in the case of millions of people using the Internet: there's no main physical location, and no bottleneck, which makes public authorities powerless.

And if this is already true on a national scale, just imagine how true it is on a global scale, when a government tries to fight a decentralized phenomenon that exists in dozens or hundreds of different jurisdictions, yet is accessible in that government's own country.

It's not Goliath against David, it's Goliath against millions of Davids, most of whom are beyond the reach of physical action.

It's so true, in fact, that we can make it a historical principle to complement the 10 already shared :

11th principle

11th principle to be learned from history: governments focus on bottlenecks (places people have to go through, leaders), and are powerless against millions of people cooperating with each other in a decentralized way.

Other examples of this principle in history: the Roosevelt administration's confiscation of gold from bank vaults rather than from individuals, and the many other examples given in this chapter and the rest of the Substack.

In fact, the only way for Goliath to win against millions of decentralized Davids is to use all the new tools at his disposal to set up a filtering and surveillance mechanism worthy of 1984.

That's what China has done, and we'll see in future articles and the book that it's what many nation-states, even the most democratic ones, are strongly tempted to do - and we're already seeing concrete signs of it today.

Example number 4: VPNs

What makes the Internet so difficult to censor is that every node in the network can communicate with every other node.

In practical terms, this means that a website hosted in Iceland can be visited by someone in Brazil, Japan or Timbuktu.

And vice versa.

By definition, a state only has jurisdiction within its borders - because, as we’ll see in more details in the future, that's the only place it can send its officials armed with a pistol.

So it's entirely possible for a nation-state to force ISPs on its territory to block a website.

This happens regularly, albeit on an infinitesimal scale in relation to the number of existing sites.

This is still real government power over a web player, but it doesn't mean that the website ceases to exist. It just prevents access from a given territory. All you have to do is cross the border to regain access to the site and the service it offers.

And today, there's no need to physically cross a border: to access the blocked site, all you have to do is connect to a site located outside the border, and use it as a relay.

The ISP responsible for censoring the target site will only see a connection to the intermediate site, which is not censored. The intermediary site, present in a country where the target site is not censored, can access it without any problem.

That's it! Problem solved.

There are several ways to connect to intermediate sites, but the two simplest are :

TOR, a free software program that easily bypasses Internet censorship by passing through relays, and encrypting and "hiding" communications in the same "pipe" or channel through which the encrypted communications of all the planet's secure sites pass (i.e. more than 95% of sites at the time of writing ).19

A VPN, which is just software that creates an encrypted connection between your IP address and an intermediary site, often located in another country.

I'll come back to this software in more detail in a series of articles on computer security, but for now just remember this: The Internet is, by default, extremely difficult to censor, because it was designed from the outset to withstand a nuclear attack by allowing every node to communicate with every other node.

Any attack less powerful than a nuclear attack will therefore tend to be very weak against the network of networks, and easily circumvented.

It's also difficult for a nation-state to ban TOR or VPNs, because :

They have many legitimate uses, such as securing your connection to a shared public Wifi network, or a secure connection to a company server for teleworkers.

Bans generally have the same effect as Hadopi had on piracy: they're a great source of jokes at the expense of the Nation-States for anyone with a little information :)

In fact, there's a direct correlation between the degree of Internet censorship in a country, and the widespread use of VPNs.

For example, here is a table taken from the statistics provided by Atlas VPN20 :

The methodology isn't perfect, as it's based on the number of downloads per country (instead of actual usage) and only on smartphones, but it's still a good indication.

It shows that, with the exception of China , the more a country censors its Internet, the more its population tends to use VPNs to bypass the censors.

(the presence of the Netherlands and Luxembourg does surprise me, though: perhaps a culture of privacy? If you've got a clue as to why they're in this ranking, share it in the comments! As for Great Britain, I'm not so surprised.)

I can tell you about my experience with Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates (1st of the above ranking), because I've been living there for years: the Internet is relatively free there (for a Gulf country), but in addition to the usual classic censored sites (like porn sites), Internet calls are blocked.

And the blocking is fine enough to block just the calls, and not the rest: so WhatsApp or Skype calls don't go through, but messages, including audio, work just fine.

This is true of all the most popular tools, apart from Zoom, which was unlocked during the pandemic to enable students to take courses remotely, and others to hold meetings, and has never been unlocked since (it's probably too ingrained for that).

The reasons put forward are mainly :

Security (these calls cannot be intercepted by the police, and are therefore "dangerous"),

Licensing issues, as a telephone operator, even an Internet one, is obliged to obtain a license in the Emirates, in theory.

So to be legal, you have to take out a VOIP subscription with one of the country's two telephone operators, which costs an arm and a leg21, and which no one outside the country (or even inside, admittedly) uses.

The bottom line? It's not that I know people who use VPNs, no: in fact I don't think I know a single person who doesn't use a VPN in Dubai.

It's an open secret, and a fact that the authorities are bound to know. They turn a blind eye to it.

And of course, since Zoom is unlocked, many people use the free version to make international calls.

From a Western expat's point of view, this is probably one of Dubai's biggest black spots - which is to say, it's not really one.

I'll have the opportunity to go into more detail in future articles about why I think Dubai is one of the states that has best understood the new world we live in, and how it is positioning itself extremely well in the market for the provision of governance services - with an absolutely unbeatable quality/price ratio.

This is another feature that makes the Internet difficult to censor: if the government censors one tool, all you have to do is use another similar one. If it censors one porn site, just go to another.

And the government can probably censor the most popular tools and sites, but not all the countless small and medium-sized sites that offer the service you're looking for.

In conclusion : a chronic impotence

Many people have noted this chronic inability of governments to fight massive, decentralized and international phenomena, and this has inspired many to create certain cryptos like Bitcoin and Ethereum, as well as DeFi (Decentralized Finance) and DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations), with the explicit aim of making them extremely difficult for governments to combat, as we'll see shortly.

But all these tools could not exist without another technology made indispensable by the Internet, and which offers us an excellent example of how a reversal of the balance of power between attack and defense technologies is highly disruptive to the powers that be, that we'll be tackling in the next article : cryptography.

In the meantime, click here to follow Disruptive Horizons on Twitter, and debate these topics with me, or just share the love :)

Note : this article is the 3rd in a series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet.

Here are the first two articles in the series:

"Exogenous Shocks, the Criminal Elite, and Increasing Gender Inequality in Chicago Organized Crime" Smith, Chris M. , 2020, and "Unintended Consequences of Prohibition", Michael Lerner

By the Gold Reserve Act

"Confiscation, Gold as Contraband 1933-1975", Kenneth R. Ferguson

Source Alexa

"Pirate Bay Future Uncertain After Operators Busted", Wired, 2008

You can easily find a copy of the code on Git Hub under the name "The Open Bay", for example.

Ironically, the only two innovations that have really slowed down the use of The Pirate Bay are Netflix, Spotify/Deezer (so a legal subscription-based offering) and... illegal content streaming.

"Global Internet Phenomena Report 2022", Sandvine

“UK government tackles wrongly-blocked websites”, Mark Ward, BBC, 2014

« Digital Economy Act 2017 », British Parliament

“UK online pornography age block triggers privacy fears”, Jim Waterson, The Guardian, 2019

« The UK’s porn block is going to be a privacy disaster”, David McCourt, NextPit, 2019

It's easy to obtain these IPs, which are displayed by P2P software to facilitate file exchanges - you just need to use a VPN to mask your real IP address.

"Hadopi : un premier internaute condamné", Le Monde, 2012

"Hadopi : 82 millions d’euros de subventions publiques, 87 000 euros d’amendes", Next Inpact, 2020

"HTTPS encryption on the web", Google Transparency Report, 2022

"Global VPN Adoption Index", VPN Atlas, 2022

It should be noted, however, that business Internet connections are not censored (but they are more expensive than residential connections, and are therefore considered to include a VOIP license).