Where it hurts most: how the Internet makes it harder for governments to collect taxes

Tax optimization and tax fraud amid an increasingly fierce tax competition

Note : this article is the 10th in a series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet.

Here are the fourteen articles in the series:

How the Internet makes Governments Impotent to Tackle Bottlenecks

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 1 of 2

How cryptocurrencies are disrupting Nation-States, part 2 of 2

Digital Shadows: How the Internet Empowers Anonymity and Challenges Governments

How the Internet prevents governments from enforcing their laws

Where it hurts most: how the Internet makes it harder for governments to collect taxes

The Web of Fraud: How the Internet Exposes Nation-States' Weaknesses

We touched on this earlier, but the growing mobility of citizens is making tax competition between countries increasingly fierce, to the point where attempts to raise taxes are sometimes completely counter-productive.

In 2023, for example, a record number of Norwegian billionaires and millionaires left the country after the Labour-Centrist coalition increased wealth tax by (only!) 0.1%1 .

Among them is Kjell Inge Røkke, who was Norway's largest taxpayer. His departure by itself meant a loss of tens of millions in tax revenue for the Norwegian government, even including the small amount raised by the tax increase.

Despite the fact that wealth tax represents a small proportion of Norway's tax revenues (around 1% according to the OECD), the country has seen a growing number of its wealthy residents move to Switzerland, which also has a wealth tax, but which does not necessarily apply to new foreign residents, thanks to the favorable tax agreements for foreigners offered in certain cantons.

This is a clear example of legislation that might have worked at a time when people were less mobile, but which only accentuates the problem it was intended to solve, because legislators have not sufficiently integrated this new paradigm into their thinking.

Big Tech and their low taxes

It's common knowledge that the GAFAMs (the digital giants Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft) were able to aggressively optimize their tax position in the 2000s and 2010s by taking advantage of two key aspects: their international character and, for some of them, the absence of any need for a physical presence in the countries where their customers are based.

The Google case

To understand this, let's look at the case of Google, which was prosecuted for tax fraud in France.

In 2013, the French tax authorities suspected Google of not paying enough tax in France, by declaring part of its income in other countries with more advantageous tax regimes, such as Ireland.

At the time, it estimated that Google would have made 1.43 billion euros in sales in France between November 2012 and November 2013, far more than the 193 million euros declared for the 2012 tax year.

Following these suspicions, a search was carried out in May 2016 at Google's Paris headquarters by around 100 officials (yes, that wasn't kidding!), including investigators from the French tax authorities and agents from the “Central Office for Combating Corruption and Financial and Tax Offences2”.

Following these searches, in September 2016, the French tax authorities claimed 1.6 billion euros in unpaid taxes, penalties and interest from Google3 , and in February 2017, Google was indicted for "aggravated tax fraud" and "aggravated tax fraud laundering" by French financial investigating judges.

Google, of course, vigorously defended itself...

and won!

In July 2017, the Paris Administrative Court ruled in favor of the company, annulling the tax reassessment on the grounds that Google's Irish subsidiary did not have a permanent establishment in France, which rendered the reassessment request non-compliant with European law.

In fact, it was even a humiliation for the tax authorities, as the public rapporteur, an independent legal expert who had the ear of the judges, had indicated that Google should not pay any more taxes than what they did in France in his opinion.

How is this possible?

Because the French tax authorities were armed with laws and regulations designed for the pre-Internet era, which presupposed a physical presence as a prerequisite for doing business.

And Google had no physical presence in France.

"But," you will say, "in that case how could the French tax authorities have searched their offices?"

Excellent question, I see you're following along, that makes me happy.

Let me rephrase:

Google did not have a physical presence in France that would trigger significant taxation.

How is this possible?

To be taxed in a particular country, a company must have what is known in tax jargon as a permanent establishment. This is "a fixed place of business through which an enterprise carries on all or part of its business."

And to fully understand why Google had no permanent establishment in France, you need to know that there were 3 separate companies in this case:

SARL Google France (its offices were searched), which acted merely as a sales agent for :

Google Ireland Limited (located in Ireland, this is the company for which the tax authorities tried to demonstrate the existence of a permanent establishment in France)

And Google, the US-based parent company (which has never been directly concerned by the French tax authorities).

So to fully understand the set-up: Google France's sole role was to find customers for the Irish company, which was responsible for providing the ad display service.

This enabled the majority of sales to French customers to be invoiced by Google Ireland, and thus to benefit from a much lower tax rate in that country (12.5% corporate tax compared with 33% in France at the time, not to mention the numerous legal tax optimizations that Google could carry out in Ireland and not in France to further lower its tax level4 ).

Google France of course had a permanent establishment in France, and paid its taxes in France on the figure it declared (Google France paid 6.7 million euros in corporate taxes in 2015 for example5 ... a straw!).

However, the tax treaty between France and Ireland explicitly states that "A permanent establishment [in France] shall not be deemed to exist if [...] a fixed place of business is used solely for the purposes of advertising, supplying information [...] which is of a preparatory nature for the enterprise [...]".

And "[a commercial agent], is considered a permanent establishment [in France] if he has [in France] powers which he usually exercises there enabling him to conclude contracts on behalf of the company6 ."

Google Ireland was able to prove that :

Google France's mission was simply to find customers for the Irish company, and that Google France earned referral fees and nothing else.

Google France did not have the power to conclude contracts; it simply referred customers to Google Ireland, which then concluded the contracts.

And that Google Ireland was therefore protected by the treaty.

That's what won Google the day, and not just once: after the French government appealed the decision, the appeals court handed down the same ruling in 2019, inflicting another slap in the face on the taxman7 .

However, a few months later, Google agreed to pay nearly a billion euros to put an end to the proceedings in France. This agreement included a criminal fine of 500 million euros and the payment of 465 million euros in additional taxes.

The details of this agreement have remained confidential, so we don't really know why Google agreed to this transaction. The Minister of Action and Public Accounts at the time, Gérald Darmanin, indicated that it was probably for reasons of image, and there was also a risk that the Conseil d'Etat would overturn the decision8 .

And large, well-known multinationals can also be very sensitive to political pressure, for a variety of reasons that are often not very public, such as obtaining subsidies or advantages, fear of being subject to restrictive regulations, etc. These agreements can therefore be a form of negotiation to obtain other advantages in exchange.

However, it should also be noted that Google managed to reduce the bill by more than 650 million euros, bringing the 1.6 billion initially claimed by the tax authorities to less than one.

And it was a major investigation and procedure that lasted 8 years and mobilized many resources.

What's more, this was clearly not enough, given that France was one of the first countries to attempt to establish a "Big Tech tax", which we'll come back to in later articles.

And Google made similar deals in kind, but far less onerously, agreeing to pay £130 million to the UK government in 2016 for 10 years of back taxes, and €306 million to the Italian government in 2017 for 13 years of arrears - sums that many commentators said were woefully inadequate in relation to the business activity actually generated - probably preferring to buy itself some peace at a lower cost.

And in most other countries, Google’s tax situation received little or no attention. This shows just how difficult it is for nation-states to tax large multinationals, especially when they use the Internet to their advantage: the fact that Google's services (displaying ads) took place on the web, rather than in any physical location, made the task much easier.

Google's optimization strategy was therefore a clear winner, saving it probably tens of billions of euros in taxes, even taking into account the company's dealings with the tax authorities.

And one wonders what would have happened if Google had had no physical presence in France, even in the form of sales agents: no offices to search, having to rely on mutual assistance with other governments - necessarily not as fluid as it should be, as we shall see.

The Apple case

Apple has also been able to play with the international nature of its business and tax optimization to minimize its taxes, but using a somewhat different strategy, not directly linked to the Internet, but rather to globalization, started before the network of networks, then accelerated by it.

Let's take the example of the company's strategy in Europe.

According to a Commission investigation, Apple managed to pay a tax rate of just 0.005% on its European profits in 2014 thanks to a tax arrangement it had validated with the Irish tax authorities through a formal tax agreement - well below the official rate of 12.5%.

In 2016, the European Commission ordered Ireland to recover €13 billion in undue tax benefits granted to Apple.

How is this possible? As with Google, it's important to understand the set-up. Apple has several entities in Europe, but the two main ones in this case were Apple Sales International and Apple Operations Europe, both based in Ireland.

Apple's model is very different from Google's: Apple sells physical products, while Google offers digital services.

However, a large part of Apple's profits come from the sale of intellectual rights linked to its products, rather than from the sale of the products themselves. These rights are held by Apple Sales International, which then charges royalties to other Apple entities for their use.

As a result, even though Apple products are sold throughout Europe, the profits from these sales are attributed to Apple Sales International in Ireland, which is responsible for selling these products. This structure enables Apple to transfer the bulk of its profits to a company based in a low-tax country.

However, the European Commission disagreed. It concluded that Apple's tax agreement with Ireland was contrary to EU state aid rules, as it allowed Apple to pay significantly less tax than other companies. In the Commission's view, this amounted to a disguised subsidy that distorted competition.

Why Ireland refuses 20 billion euros (or 10% of its GDP) ?

An unexpected windfall that Ireland was eager to cash in, wasn't it? Especially since, with the penalties for late payment, the 13 billion euros could turn into 20 billion euros, or 10% of Ireland's GDP at the time (!).

Well... not really, no: the Irish parliament voted by a majority to reject payment of the back taxes, and in the process the Irish government officially appealed the decision , claiming that there had been no violation of Irish tax law and that the Commission's action constituted "an intrusion into Irish sovereignty", national tax policy being excluded from the European Union treaties (Apple subsequently joined the appeal).

Why refuse a windfall equivalent to 10% of its GDP? Because the Irish government has a long-term view, and didn't want to sabotage its position in the market of jurisdictions fighting to attract the headquarters of multinationals, by showing them that it will defend to the bitter end the agreements it has made with them.

And it's no wonder when you look at the figures: US multinationals account for 25 of the 50 largest Irish companies; they pay over 80% of all Irish corporate taxes (around €8 billion a year) , they directly employ 23% of the private sector workforce , and they indirectly pay half of all Irish payroll taxes.

So it's understandable that the Irish government doesn't want to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.

And it also shows you that more and more states are going to position themselves on the jurisdiction market to offer unbeatable terms to entrepreneurs, businesses, digital nomads, etc., and that the best ones are going to create a reputation for themselves by fighting to the bitter end to defend the terms they offer, even against external attackers.

The others will lose their customers.

In 2020, the EU General Court upheld the Irish government's position and annulled the Commission's decision, finding that it had failed to prove that the tax agreement constituted illegal state aid.

In 2021, the Commission appealed this decision, and as I write this, the appeal is still pending.

Other multinationals

A study summarizing years of research9 estimates that 35% of the profits made abroad by multinationals is artificially shifted to low-tax countries, representing around 1,000 billion dollars.

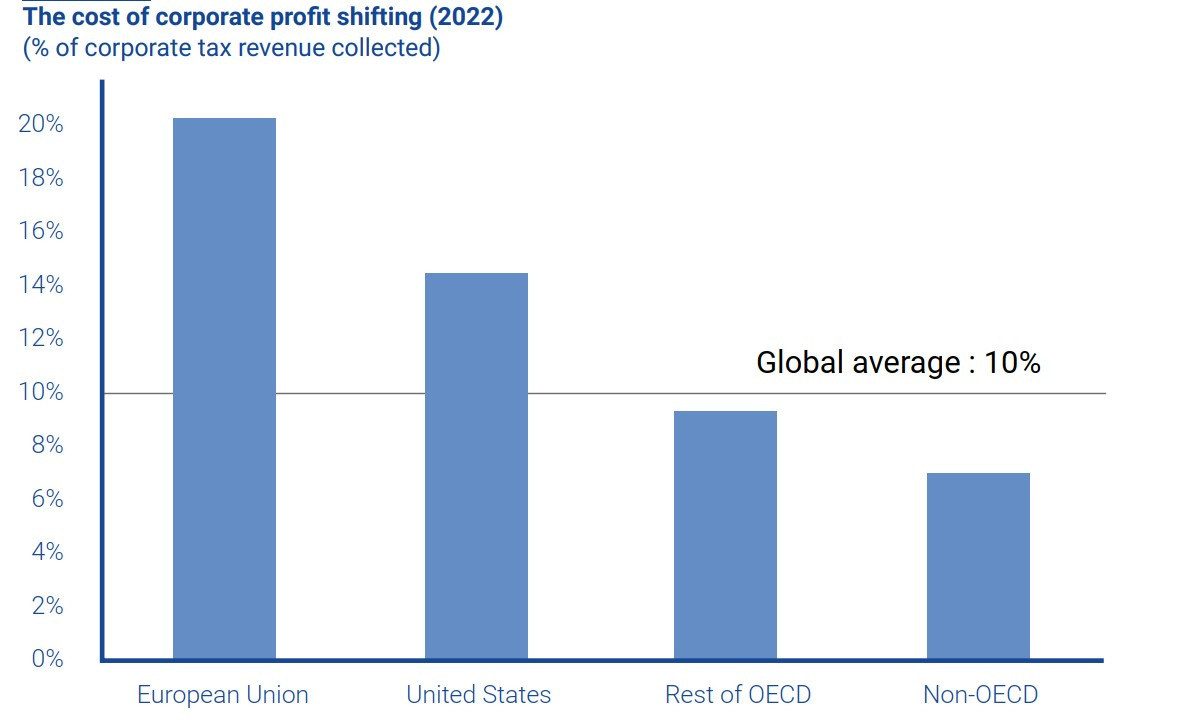

It is estimated10 that this causes EU countries to lose around 20% of their corporate tax revenues, the USA 15%, and the rest of the OECD 9%.

And for the little ones? The case of digital nomads

I've covered the case of digital nomads, whether employees or entrepreneurs, in detail in this article, and how they can legally optimize their taxes, so I won't go into it again here: I recommend you consult the article if you're interested in the subject.

Let's just say that millions of digital nomads who leave their native country to choose one that offers a package including sunshine, white sandy beaches (or snow-capped mountains, or whatever landscapes take your fancy), attractive laws, quality of life and low taxes is very attractive… and very disruptive for the finances of nation-states.

The difficulties of combating international tax fraud

Beyond these (legal) tax optimizations, which are difficult to combat, the fight against (illegal) fraud is also highly complex and costly.

The French Cour des Comptes explains very well the problem faced by nation-states on this subject in a 2013 referral11 :

"Open borders, dematerialization of trade, transport facilities and tax competition contribute to the development of international tax fraud, while borders still constitute an obstacle to the control and punishment of such fraud despite the progress made in cooperation between states."

Let's take a specific example of what should have been an easy case, the prosecution of Panama Papers cases in France.

The Panama Papers were a massive leak of documents in 2016 from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, that revealed how numerous public figures, politicians, celebrities and companies around the world used shell companies, trusts and other complex financial arrangements in tax havens to hide assets, avoid paying taxes and launder money.

Thousands of documents concerning potential tax evaders have literally been handed to the French justice system on a platter. Material for easy case analysis, and efficient justice, don't you think?

Well, not really. Here's what Le Monde had to say about it in 202112 :

"In France, the 29 judicial investigations opened on the basis of the Panama Papers have taken up a substantial part of the time and energy of the National Financial Prosecutor's Office (PNF in French13), which is responsible for investigating the most high-profile financial cases.

After five years of investigation and dozens of requests for international criminal assistance sent to Luxembourg, Delaware (USA), Panama and the British Virgin Islands, PNF magistrates are still working on fourteen cases - "particularly investigations involving financial intermediaries, as these are the most complex cases, where it is very difficult to prove guilt", explains one magistrate.

[...]

To date, the PNF has closed fifteen cases: ten have been dismissed, but five have resulted in a "guilty plea" - a fast-track procedure that avoids a court hearing. These five cases resulted in criminal fines of 3.47 million euros, with prison sentences ranging from three months to one year suspended.

So we can see that, even with a lot of information served up on a platter, it took the PNF five years to carry out 29 investigations, of which only 15 were successful, and 10 were dismissed - and this "occupied a substantial part of the PNF's time and energy", all to earn less than 4 million euros!

If the PNF finds it so difficult to carry out investigations - and bring about convictions - when it has access to so much compromising information, what difficulties does it encounter in a "normal" situation, when faced with people who know how to stack borders and hide their tracks?

VAT on digital products in the EU : an example of the powerlessness of states to enforce their taxes beyond their borders

Back in May 2002, the European Union, probably sensing that the Internet was going to enable many companies located outside the EU to sell to European residents, introduced Directive 2002/38/EC, under the dubious name of "VAT: special arrangements applicable to services supplied electronically14".

This directive said (and still says):

"Electronically supplied services include services such as cultural, artistic, sporting, scientific, educational, entertainment, information and similar services as well as software, video games and computer services generally. The result is that:

for specified electronically delivered services, when supplied by a non-EU operator to an EU customer, the place of taxation is within the EU and accordingly they are subject to VAT;"

So for over two decades now, any company based outside the EU selling e-books and e-learning courses to EU residents, for example, has had to pay VAT in the customer's country.

And what's interesting is that this is 1) right in my line of work (I sell online training) and 2) I've been very well connected to the American and Canadian markets since 2010, having many English-speaking entrepreneur friends selling online training, that I'm also very well connected to the Brazilian market, and to the Spanish-speaking Latin American market, I know entrepreneurs from there who have been doing a lot of sales in Europe for years and I can tell you one thing:

Absolutely none of these entrepreneur friends 1) have paid VAT in the EU over the last two decades, even though some have sold tens of millions of euros worth of digital products in the EU, and 2) have received even the beginnings of a shadow of a letter, email or carrier pigeon from European tax authorities on the subject.

Why? For many reasons:

The overwhelming majority of them are unaware of this obligation. And that's only to be expected: they don't have the time to keep up with all the tax and legislative changes in their own country, so when it comes to other countries, you can imagine...

The same can be said of their accountants: it's already their full-time job to keep up with legal developments in their own country, and even they can't keep up with everything, so they don't have the time (or the inclination) to keep up with legal developments in other countries.

The few who are aware of this, it has to be said, don't usually give a damn: they already have enough taxes to pay locally, without having to worry about taxes from faraway countries where they'll never set foot, except perhaps as a tourist for a maximum of 15 days in their lives.

It is extremely difficult for tax authorities in one country to enforce their laws in another (which is also true of all laws in general, not just tax laws, as we saw in this article) :

It is extremely difficult to identify offenders in the first place.

If by any chance these offenders are detected, there is very little chance that they will agree to obey an injunction from a tax authority in a country in which they do not live (this is reinforced by the 1st point, which is that the majority of them are not even aware of their obligations).

The tax authorities in the country where the offender is located have zero time, zero people and zero budget to devote to another country's tax laws, not to mention absolutely zero motivation to do so.

Even if an investigation can be carried out despite all these obstacles, and it is proven that the offender owes money to the tax authorities in the country where he has customers, he generally has no seizable assets in that country, so how will the tax authorities recover this money? Yes, some countries have agreements between themselves to assist each other in such cases, but these are complicated, costly procedures with uncertain results, as we shall see in more detail.

Which can be said of the whole process, by the way: can you see how time-consuming and costly the investigation is, and how uncertain the results? Tax authorities get a much better return by focusing on local mono-country offenders... and that's what they do.

E-commerce VAT fraud on physical products

Beyond VAT on digital products, since 2015, when a company sells a physical product online that is delivered to a customer resident in an EU country, it is expected to pay VAT in the country where the customer is located, regardless of its physical headquarters.

You'll note that I wrote "supposed", and it's no coincidence: for a very long time, e-commerce companies located outside the European Union have been evading this VAT en masse.

Judge for yourself: in a 2019 report, the Inspectorate General of the French Ministry of Finance estimated that 98% (yes: that's not a typo) of e-commerce sites located outside the European Union, registered on a platform like Amazon or Cdiscount and selling in France, were evading VAT15.

And more generally, it is estimated that VAT fraud of all types will exceed 60 billion euros in 2021 in the EU16.

This was far, far from trivial. And it meant that all these companies benefited from a massive advantage, enabling them to sell the same products 20%17 cheaper than law-abiding companies.

What can the public authorities do against such massive fraud, committed by players outside their physical sphere of action?

Fortunately, you have recently read the 11st principle that history teaches us, so you know: tackle the bottlenecks.

In this case, marketplaces with a physical presence in the EU, such as Amazon or Cdiscount: a European directive has made them co-responsible for paying VAT from 2021.

Since then, they have been deducting VAT from all customer payments at source, and transferring it to the country in which the customer is located.

This was very effective… but only for that part of the fraud that was easiest to measure and control.

This is because the 2019 report made no mention of dropshipping, which involves a seller promoting products and then, once the sale has been made, placing an order directly with the supplier, who then delivers directly to the customer.

When the seller and supplier are outside the EU, and the seller doesn't sell via a marketplace but via his own websites, good luck to the authorities in catching a significant proportion of this trade.

The EU has attempted to combat this fraud by making it compulsory to pay VAT on all parcels from outside the Union, whatever their price, whereas previously there was an exemption below 22 euros, which was widely used by fraudsters.

It's a good initiative… except that there's no sign that most dropshippers are now paying VAT.

In Belgium, for example, customs officials estimated in 2021 that one out of every two parcels involved an economic or tax offence18.

And in France, customs officials believe that they do not have the means to control the 7 million parcels that pass through airports every year19.

What's more, although I sell entirely digital products and therefore do neither e-commerce nor dropshipping, I frequently meet entrepreneurs in these fields - including trainers on the subject - and the feedback they've shared with me is clear: this directive has worked for marketplaces, but for dropshippers, it's a fly in the ointment. Everyone is still happily evading VAT, with no real repercussions.

So it seems that the EU has tackled the "Napster" of VAT fraud, and must now tackle the VAT equivalent of "Bittorrent + The Pirate Bay".

We've already seen clear examples of what history teaches us when nation-states tackle massive, international, decentralized phenomena: the EU will probably fail, and if it succeeds, it will never be completely or even overwhelmingly, and at enormous cost in terms of budget and, above all, added friction in the functioning of civil society and therefore cost to the economy.

The difficulty for a State to collect tax debts in another country

There is thus a principle recognized in international law, and has been for several centuries, that the tax and judicial systems of one country cannot apply the tax laws of another20 , which includes the impossibility of forcing a resident of the requested country to pay the requesting country21.

This principle can be waived on a case-by-case basis in bilateral treaties, but such cases are very rare: for example, the United States has signed a double taxation treaty with 66 countries, but only 5 of them include a clause on assistance in collecting another country's taxes, with numerous restrictions22 .

It should be noted, however, that this is not true for the countries of the European Union, which have specific regulations on this subject23 : as we shall see, the EU must increasingly be considered as a single country.

However, as we shall also see, many things that work in theory no longer really work in practice as soon as borders are added: according to a report by the European Commission24 , even armed with domestic law, EU countries were only able to recover 67 million euros via this mechanism in 2016, the best year studied! To put this sum in context, EU countries received tax and social income of 5,139 billion euros in 201625 .

The sums recovered by this mechanism therefore represent 0.001% of EU countries' tax revenues.

The same report indicates that it is not possible to measure precisely the percentage of sums recovered in relation to those claimed, but that France estimates it at around 5% two years after the claim, and in the best years "between 7 and 8%"!

Another estimate of the percentage of sums recovered by the country in which the recovery attempt is made (and not in the claimant's country) shows that, for the years 2013 to 2016, results range from less than 3% (for 16 of the 28 member states at the time!) to 26.5% for Finland, the EU champion.

Only 4 EU countries manage to collect more than 10% of the sums claimed by another member state (Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland), and a further 4 recover more than 5% of the sums claimed (Belgium, Germany, France and Slovenia).

18 member states have complained about the number of requests they receive, deeming them "very heavy and burdensome for them", and 17 have complained about a lack of internal resources to deal with them, even though the total number of recovery requests in 2016 was... 16,403, for the whole of the EU, a figure per country well below what they have to deal with internally for their own nationals.

So we can see that, even within a very strong Union, with laws, directives and regulations that provide for everything at a theoretical level, the friction added by borders is such that recovery performance is absolutely abysmal.

I'll leave you to imagine the actual recovery rate between countries that are not part of a union as close-knit as the EU.

Lack of administrative skills for international enforcement

Another example is the negotiation and application of international tax treaties. In a 2019 letter26 , the French Cour des Comptes states that "in the face of growing economic and budgetary challenges, the economic expertise required prior to negotiating these agreements appears insufficient".

After estimating the loss of corporate income tax due to aggressive international tax optimization (largely enabled by the Internet) at between 2.4 and 6 billion euros a year, the Court points out that "with the development of the digital economy, the risk of attrition from the tax base presents a new acuteness", and that the administration's competence in this area "is modest compared to the scale of the issues at stake27 ".

The Court goes on to point out that the number of staff in the division responsible for negotiating treaties is 10, a team size far too small to be able to handle all the files efficiently, with "844 files pending in 2017 for a processing capacity of around 300 cases per year".

In conclusion

So far in this series, we've seen many areas in which nation-states are being disrupted by the Internet: the growing mobility of their citizens, the obsolescence of their labor laws in the face of international remote working, massive, decentralized and international phenomena like The Pirate Bay and Bittorrent that are impossible to stop, cryptocurrencies, and many others.

But here you have an example of a disruption that really hits where it hurts: in the very ability of states to collect their taxes, and therefore to finance their budgets and therefore their promises, the fulfillment of which is extremely important for their legitimacy and prestige.

Good tax collection motivates them in the extreme, and yet we see that, in this area as in others, the Internet is disrupting them just as much.

Admittedly, international cooperation on the subject is growing ever closer, but as you have seen in this article (and in others), it is not sufficient to counterbalance this disruption, and is slow, ineffective and costly.

And, as we'll see in a future article, this and all other disruptions are coming at one of the worst times in the history of nation-states.

Coming soon

In the next article, we'll delve into the frauds made possible by borderlessness, going beyond "simple" tax frauds.

Stay tuned, and in the meantime, click here to follow Disruptive Horizons on Twitter (and here on Nostr), and debate these topics with me, or just share the love :)

The series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet

This article is the 10th in a series on the disruption of nation-states by the Internet.

Here are the first nine articles in the series:

"Norway counts the cost of its new wealth tax as billionaires flee to Switzerland", Charlotte Gifford, The Telegraph, April 2023

Office central de lutte contre la corruption et les infractions financières et fiscales

"Le fisc réclame 1,6 milliard d'euros d'arriérés d'impôts à Google", Richard Hiault, Nicolas Richaud, Les Echos, 2016

Including the famous "Irish Double" and "Dutch Sandwich", which basically reduced taxation to zero. This legal loophole was closed in 2015, with a transition period that allowed multinationals to use it until 2020, but other techniques, such as "Single Malt" and "Green Jersey" have emerged

"Google échappe à un redressement fiscal en France" Thomas Chenel, Les Echos, 2017

Convention fiscale entre la France et l'Irlande, 1968, articles 2.9.b.ee and 2.9.c

"L'annulation du redressement fiscal de Google confirmée en appel", Le Parisien, 2019

"Pourquoi Google a fini plier face à l'Etat français", Ingrid Feuerstein, Les Echos, 2019

« Global Tax Evasion Report 2024 », EU Tax Observatory, 2023

“The Missing Profits of Nations”, Thomas Tørslov, 2023

"Les services de l'État et la lutte contre la fraude fiscale internationale", Cour des Comptes, 2013

“« Panama Papers » : cinq ans après, des milliards récupérés et plusieurs condamnations”, Le Monde, 2021. Note that the billions mentioned in the title correspond to $1.36 billion recovered in... 24 different countries.

Parquet National Financier

"Sécurisation du recouvrement de la TVA", November 2019, Claude Wendling, Florence Gomez, Inspection générale des finances

The amount of VAT in France in 2019

"Commerce en ligne : pourquoi la fraude à la TVA est si difficile à contenir", Ingrid Feuerstein, Les Echos, 2019

"The Revenue Rule: A Common Law Doctrine For The Twenty-First Century", Brenda Mallinak, 2006

"Changing the Norm on Cross-border Enforcement of Debts", Philip Baker, 2002

See footnote 13

MARD Directive, or "Mutual Assistance in the Recovery of Debt" of 2002, supplemented by Directive 2010/24/EU of 2010 [REF A VERIFIER!!!]

"Evaluation of the use of mutual tax recovery assistance on the basis of Directive 2010/24/EU by the EU Member States", 2017. [REF A VERIFIER!!!]

"Tax revenue statistics”, Eurostat, 2022

"Les conventions fiscales internationales", Cour des Comptes, 2019

This lack of skills is largely due to the fact that most people are single-country, as we'll discuss later.