10 Principles of History for predicting the future (2/2)

To better predict how nation-states will be disrupted by the Internet and globalization

(Note : the first 5 principles are here, I recommend that you read them first if you haven't already.)

The Peace of Westphalia

The year is 1648, and it's been 30 years since a war between Catholics and Protestants1 raged across Europe, claiming between 3 and 4 million lives - a fifth of the population of the territories concerned2 .

Exhausted by so many atrocities - and many more conducted in other wars of the same type3 - the multiple parties involved in this war agreed to compromise, resulting in the Peace of Westphalia.

Among the treaty's many provisions is the recognition of Protestantism4 as an official religion, on the same footing as Catholicism, and the freedom of each ruler to choose the state religion for his territory... but the absence of any obligation on his subjects to follow this religion: everyone can privately practice one of the recognized religions, marking the beginning of the religious freedom that characterizes the modern era.

This seriously undermined the power of the Catholic Church, which had pushed the Catholic states to fight against the Protestants, in this and previous wars5 , to such an extent that Pope Innocent X declared in a papal writ6 - which according to medieval dogma is supposed to be infallible7 :

We declare that the said articles [of the Treaty of Westphalia.... ] are and shall be legally and perpetually null and void, valueless, invalid, perverse, unjust, condemned, reprobate, vain, and without force or effect, and that no one is bound to observe them, either individually or as a whole[...].

Furthermore, as a further precaution, for as long as necessary [...] we condemn, reprobate, extinguish, annul and deprive of all force and effect the said articles and all that is prejudicial to them established above, and we protest against them and declare their nullity in the eyes of God [...].

We further decree that [... the document of this writ] shall never and under any circumstances be challenged, invalidated, annulled or revoked by legal or polemical means, challenged by law [...]; but that it is and shall be in perpetuity valid [...].

As you can see, the Pope was particularly upset, and in the Middle Ages, this document would have been like a bomb.

What effect did this have on the Peace of Westphalia, and the behavior of Catholics?

Roughly zero.

As we saw in the previous article, Protestantism, aided by the printing press, had had time to spread sufficiently, and to change mentalities, even for Catholics.

And that's why the Church wanted to regulate the printing press: it was, and still is, a machine for changing the story people tell themselves.

The Protestants changed the story millions of people told themselves from "I believe that the Catholic Church is the only acceptable version of Christianity, and that the Pope is infallible because he is guided by God" to "the Catholic Church has misinterpreted the divine words contained in the Bible, or even invented rules that don't exist there, to serve its own earthly interests, as anyone who reads the Bible directly can see. The Pope is therefore not only fallible, but also corrupt, and we must stop listening to him, and to the whole Catholic Church".

Among Catholics, not many still believed in the Pope's total infallibility, partly because the Protestants' arguments had hit the nail on the head, and above all because those who still did were not ready to relive the countless atrocities of the many wars of religion.

So the pope could rant as much as he liked: in practice, nobody took any action, because nobody who really mattered believed any longer in the pope's relevance to legislate in this way on important aspects of everyone's lives.

This was a major step in the decline of the Church's power, 2 centuries after the invention of printing, and 130 years after the start of Protestantism.

6th principle

6th principle to be learned from history: people's obedience and motivation to follow someone's instructions come directly from the beliefs they hold in their heads.

If they believe a story that says you're legitimate, they'll listen (Catholics in the Middle Ages, who fought "heretics" and took part in crusades).

If external conditions make them doubt the story, they listen to you less and question you more (Catholics after the Wars of Religion in Europe).

If these conditions make them believe in a different story, they won't listen to you anymore, and may even fight you directly (Protestants after the dissemination of Luther's 95 theses).

7th principle

7th principle to be learned from history: cheap, hard-to-censor communications technologies are very powerful in changing the stories people believe.

Another example of this principle in history: the philosophy of the Enlightenment, which spread rapidly thanks to the printing press, was a major cause (along with other factors) of the gradual replacement of the monarchies of divine right that prevailed in Europe by democracies, because this philosophy meant that enough people no longer believed in the sacred, important, necessary and divine character of royalty. The printing press thus enabled the spread of a new theory that changed the stories people told themselves about the kind of government they should have.

8th principle

8th principle to be learned from history: When conflicting stories fight to exist in people's minds, it sometimes takes wars to decide which story will win out.

The only way that history has found to avoid a bloodbath when a new story wants to exist and take the place of the old one is to give the new story the right to cohabit with the old one (in religion, this means freedom to practice one's religion, in politics and in other fields, freedom of expression, i.e. the right to try to replace existing stories with new ones, with arguments instead of fights).

And even without war, there are at least always battles of the mind, with pamphlets, debates, marketing and propaganda operations.

Other examples of these principles in history: every war aimed at the permanent occupation of a territory is fundamentally aimed at changing the story that the inhabitants of a territory have in their heads (as well at monopolizing the potential resources of that territory).

In the days of the Roman Empire, the aim was to replace the story "I belong to people X or kingdom Y" with the story "I belong to people X or kingdom Y AND ESPECIALLY to the Roman Empire"; in the Middle Ages, the aim was to move from "I serve lord X" to "I serve lord Y"; with the wars of the modern nation-states, the aim is to move from "I am a citizen of country X" to "I am a citizen of country Y"8 .

If wars aimed at occupying a territory have become sacrilegious (as we saw with the Western world's reaction to Russia's invasion of Ukraine), it's because the governments of most nation-states now agree that peoples have the right to govern themselves, and that it's not permissible to use force to change the story in their heads - even if this principle is far from perfectly applied, as we shall see in other articles.

If today there has been this change in mentality, it's because the horror of the wars of the 20th century, with their gigantic human and financial costs - linked to the evolution of ever more efficient technologies for killing others - has made most people realize that fighting on a large scale to change the political allegiance people have in their heads was no longer worth it - just as Catholics realized in the 17th century that fighting to change people's religious allegiance was no longer worth it.

The European Union is an example of a peaceful approach aimed at replacing the story in people's heads of "I'm a citizen of country X" with "I'm a citizen of country X AND the European Union".

And of course, the transition from monarchies to republics and democracies came from the same phenomenon: basically, there were kings who ruled before because people believed (= told themselves a story) that kings had a legitimate reason for doing so (often, that God or the Gods or certain Gods had chosen them), then when people stopped believing (= when they told themselves another story), they wanted to change the regimes in place so that they were in line with these new beliefs.

We'll see throughout future posts on this blog how the Internet and all the technologies it spawns are freeing creative minds to come up with new stories to tell us in order to cooperate.

La Fronde

At about the same time as the Wars of Religion were dying out, a quasi-civil war was breaking out in France.

Taking advantage of the anger of a tax-burdened populace - state spending had quintupled between 1600 and 16509 - and the fact that King Louis XIV was a minor and the kingdom governed by a regency, the officers of the robe (parliamentarians and senior civil servants) revolted against the king, and proposed, among other things, to veto royal taxes, to abolish the lettres de cachet - which the king could use at will to imprison or banish anyone, without trial - to abolish the intendants (equivalent to prefects, and appointed by the king), and to reduce the taille (the most important tax at the time) by a quarter.

Many nobles joined the movement, which experienced so many twists and turns, alliances and counter-alliances, and other improbable endings that were celebrated as major victories but turned out to be temporary, that it would be tedious to summarize them all here.

The aim of the frondeurs was simple: to limit the power of the king, who was increasingly ruling alone, without the help of the nobles, and who also wanted to impose on them duties that traditionally did not affect them - notably taxation.

This was a direct reaction to their loss of power partly due to the invention of gunpowder, and the inversion of the balance of power between attack and defense we saw in the 5th principle in the previous article.

The result was clear: despite temporary victories here and there - the royal family even had to flee Paris at one point - it was the royal power that won.

It had the most powerful army, technology was on its side, and it could easily take many of the strongholds that had previously protected nobles behind impenetrable walls.

And since, in the end, you always get more out of asking politely with a gun in your hand than just asking politely...

From proud lords reigning almost unchallenged over their fiefdoms, nobles were reduced to courtiers who had to please the King at his court, a strategic location where many important decisions shaping the kingdom were taken10 , and from which they could be expelled at any time for any reason.

They had better behave themselves - and had to compete with bows, bon mots and flattery for crumbs of the King's attention.

The feudal era was well and truly over.

9th principle

9th principle to be learned from history (and which also applies to the example of the Catholic Church shared above): when an established power is disrupted, it does not surrender without a fight, even if the outcome of the battle is set by external conditions over which it has no power.

Other examples of this principle in history include the famous "Corn Laws", passed by the British Parliament in 1815, which severely restricted the import of cereals, as trade was picking up after the Napoleonic Wars, and the sudden influx of cereals at unbeatable prices greatly destabilized the nobility, whose dwindling incomes still came from the land.

They voted for a law that benefited them, to the detriment of all those who could benefit from cheaper food, especially city dwellers11.

The nobility thus took advantage of a brief window of opportunity, during which they still had significant political power - disproportionate to their economic power, which had been declining for over two centuries - to try to keep their privileges a little longer.

Another example

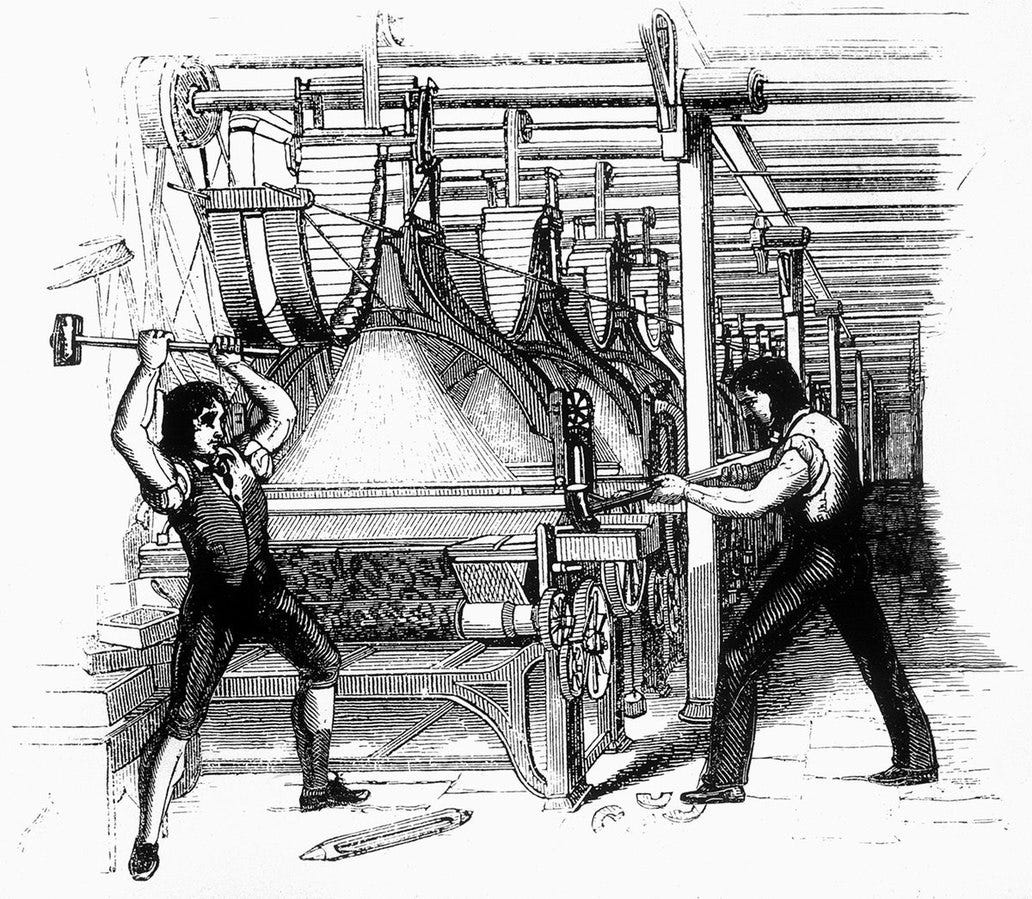

The Industrial Revolution in England in the early 19th century rapidly transformed its economy, society and mores. Modern manufacturing replaced the old craft methods, creating an unprecedented demand for factory workers, but jeopardizing traditional jobs, particularly those of craftsmen who worked from home.

One of the most emblematic and famous groups of this era is undoubtedly the Luddites. These workers, whose name is derived from a mythical character, Ned Ludd, revolted against the weaving machines that threatened to deprive them of their livelihood, and set about destroying the machines.

But these actions were not just an act of rebellion, they were also a desperate reaction to a situation over which they had little or no control.

They saw the world they knew changing before their eyes, their traditional way of life becoming obsolete, and they felt powerless in the face of the avalanche of technological change.

In the end, the Luddites were severely repressed, their revolt stifled, and their impact on the Industrial Revolution was absolutely minimal, because the factors that made their trade obsolete were completely beyond their control: all the Luddites could have achieved would have been to gain a few years.

It was like watching beavers build a twig dam to stop a tsunami.

The birth of modern nation-states

We are now at a pivotal moment in history, when relative religious freedom had been hard won, the sovereignty of states over their territory recognized in Europe (with the Peace of Westphalia), and feudal power definitively curtailed in favor of a centralization of power in the hands of the king (the Fronde, which concerned France but was emblematic of what was happening in Europe at the time).

These were the first stages in the emergence of modern nation-states, which came into being thanks to a process of "nation-building" that was a steamroller in Europe.

The kings and queens, freed from the stranglehold of feudalism, consolidated their power and laid the foundations for centralized government, but the formation of a nation-state was not just about drawing borders on a map: it was about creating a nation, a people who shared a common identity.

This is where our friend "nation-building" comes in.

In the 18th century, with the rise of nationalism, states began to develop symbols and traditions to reinforce their national identity and sense of belonging to the same community. National anthems were written, flags designed and national languages promoted.

France, for example, made the use of French a central point of its national identity, actively promoting French throughout the country and strongly discouraging the use and transmission of regional languages12 .

This choice of a single language for a territory previously made up of a myriad of languages and dialects was only possible because the language of the precise territory where the first printing works had begun to print books had an indecent advantage: as the majority of books were printed in this language, it spread throughout the country much faster and farther than the others.

The winning language was often that of the country's capital, or of the most prosperous and commercial city, which had the means to invest in the first printing works, and to sell printed books over a large geographical area13 .

We see here how printing not only disrupted the dominant religion, but also the very political, social and cultural organization of countries: and we'll see in the rest of this blog (and the book) that the Internet is a printing press on steroids.

In the 19th century, the process of nation-building gained even greater momentum with the advent of new technologies: railroads, the telegraph and the press connected people as never before, reinforcing the sense of national belonging.

Countries like Italy and Germany, previously fragmented into small, often warring states, or in complex feudal relationships with each other throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, unified under a single national banner.

This is one of the direct consequences of the 6th principle: "People's obedience and motivation to follow someone's instructions come directly from the beliefs they hold in their heads".

Nation-building has consisted in changing the beliefs of many minorities so that they come to think "I am a citizen of country X, where nation Y lives, and I speak language Z, the common language of our nation".

So, for example, "I'm a French citizen (i.e. a citizen of France, in which the French nation lives) and I speak French", rather than "I'm a subject of Count X, my king is the King of France, and I speak Breton and a little Latin".

Understanding how the nation building process shapes how we see ourselves today is crucial to understanding how it can be disrupted, so as an example, let's do a thought exercise and examine François, who lives in Brittany, at two different times: 1400 and 2000.

For the purposes of the exercise, François is the same human being at the genetic level, but of course the era in which he was born and raised has shaped different beliefs in him, including in the way he perceives himself.

The François of 1400 lived in Brittany, which was then a semi-independent duchy within the kingdom of France.François would perceive himself primarily through local affiliations - his family, his village, perhaps his profession. His identity was largely linked to the Catholic religion, local customs and the Breton language.

Politically, he was a subject of the Duke of Brittany, and by extension, of the King of France, but these ties were rather distant and abstract for him: like almost all his contemporaries, he never saw the King in his life, and only saw his "face" on the coins he used. The king was perceived a little like the Council of Europe for an EU citizen today, or the United Nations Security Council for an American: Francis knew that it existed and that it had theoretical power over his suzerain, and therefore theoretically over him, but he didn't really know how this power was articulated, and thought that it was rather the Duke of Brittany who was his "chief".

This François certainly didn't see himself as "French" - a notion that didn't exist at the time - but as a member of his direct community, subject of the Duchy of Brittany, and by extension subject of the Kingdom of France, a rather vague and nebulous territory of which François never saw a map in his life.In 2000, François' concept of himself is very different. He lives in a post-nationalist world, where Brittany is a region of the French Republic. François probably sees himself more as a Frenchman from Brittany, rather than a Breton being French (although this may vary according to his attachment to his regional roots), or even European. He speaks French and just a few words of Breton.

He is aware that he is part of a nation, France, with a common history, flag, currency, constitution and political institutions. He has the right to vote and is subject to the same national laws as other French citizens. Socially, his position is probably defined by a mixture of factors, including education, profession, gender, race and other elements of personal identity.

The main difference between the François of 1400 and that of 2000 is the scale and nature of their identity.

In 1400, François' identity is local, rooted in direct personal relationships and local traditions. In 2000, his identity is embedded in larger, more abstract structures, and is influenced by the concept of nation, the fruit of the development of nationalism.

If, for example, the town of Narbonne, located on the borders of the kingdom in relation to him, had been invaded, the François of 1400 would not have felt invested with a "sacred" mission to defend this town, which was part of a different duchy, with a different language and culture, and where he had never set foot.

He might have been part of an army raised by the Duke of Brittany at the request of the King of France, and so might have taken part in a war of defense out of loyalty to his Duke and honor for his promises to him, but not out of patriotic duty.

He might also have felt a sacred duty to enlist in an army of religious volunteers if Narbonne had been attacked by an army of a religion different from his own. Loyalty to his suzerain and his Church: this was what could mobilize François to risk his life. Not the defense of the "kingdom of France".

Conversely, the François of 2000 (or even 1900) would have felt an attack on Narbonne as an attack on France and the French, a nation and people to which he felt he rightfully belonged, and as a personal wound. He would then have felt it a sacred duty to risk his life to defend the fatherland, the nation, and France.

Because the need to belong to a community, and the desire to protect and contribute to it, has probably always existed for our specie. But more often than not, it was a direct community, in which you knew most, if not all, of the members14.Between the two François, the notion of patriotism developed gradually, at the same time as the nation-state of France was developing - the word was actually coined in French in 1750.

Patriotism attaches this need to belong and contribute to an imaginary community, the homeland. It's an imaginary community because you don't know the majority of its members, but you imagine that they belong to the same community as you, thanks to various signs (language, culture, shared history - often partly imaginary too, because "forced" to fit into the mold of the "homeland's" history15 - similar education, etc.).

Do you understand how the two different stories told by these two genetically identical Francois have a major influence on behavior that can even lead to self-sacrifice?

We've moved from one story to another, because a nation-state, as with almost any type of society, is an imagined community that enables millions of people who have never met before to cooperate with each other16.

So the François of 2000 feels that Narbonne is part of the same community as he is, even though he has never set foot there and knows no one personally from the town, whereas the François of 1500 doesn't think Narbonne is part of his community.

For the printing press, then the press, radio and television, aided by a common language shaped by all these tools, meant that the François of 2000 imagined himself part of a global community called the "nation", whereas the François of 1500 recognized as his community what he knew directly, or was very close to.

Now imagine what the Internet can do - is already doing - to create imagined communities. And understand that the Internet knows no borders.

Do you see the disruption coming to nation-states?

But what exactly is a nation-state?

We'll be talking about it throughout this blog and the book, so it's important to define the concept: basically, it's a Nation - i.e. a people sharing many commonalities, such as a history, culture, customs, language, as well as often (but not always) religion and ethnicity - which has endowed itself with a State to represent it and act on its behalf.

The European countries, made up of numerous feudal fiefdoms, diverse cultures, languages and dialects, homogenized all these factors through "nation-building" to form a single nation, which eventually gave itself a state.

The nation-state is therefore a political construct that seeks to align national identity (the feeling of belonging to the same nation) with the political limits of the state.

In the end, that's the theory: in practice, this ideal is never really achieved.

Even the nation-states often cited as examples approaching the ideal of the concept, such as Japan or France, have minorities with their own culture, language and/or religion17 .

And there are states with several nations, like Belgium or Lebanon18, and stateless nations, like the Kurds (divided between 4 states) or the Jews before the recreation of the state of Israel.

And this process of nation-building was not a smooth one: as we saw in this article, it often involved the suppression of regional cultures and languages, as well as the forced assimilation of minorities, and of course eventually led to devastating tensions and conflicts between fully-formed nation-states, with the two world wars of the 20th century and their 87 to 103 million dead culminating19 : nationalism, as a unifying factor for a nation, proved to be the perfect tool for launching an entire population into war, whereas previously wars were primarily the affair of professionals who represented only a small part of a population, and for increasing support for war - thus, unfortunately, part of the populations concerned were extremely enthusiastic at the very start of the 1st world war, for example, partly out of exacerbated patriotism and nationalism20 .

And, for the first time, nationalism prompted many people to die for their homeland.

In the Middle Ages, one could die for one's lord, for one's religion, to defend one's community, or for one's honor (by keeping one's vows and promises), but dying for one's "fatherland" was inconceivable, as there was no fatherland as such.

There were certainly conflicts involving large swathes of peoples before the advent of modern nation-states, such as the Mongol invasions or the wars of religion in Europe, but the two world wars involved an unprecedented mass mobilization that would have been impossible before the advent of nation-states21 .

Similarly, it's doubtful that Napoleon could have mobilized such a large army if France hadn't already been well on its way to becoming a nation-building country by the time of the Napoleonic Wars22.

By examining how nation-states came into being, we can realize that, while the political and cultural institutions we live with seem ubiquitous and so obvious that we find it hard to imagine a world in which they don't exist, they are in fact the fruits of a set of historical and technological factors that saw them come into being and replace previous institutions, and are sometimes very recent in history.

10th principle

10th principle to remember from history: new factors, especially technological ones, can disrupt existing institutions, even those that seem immortal or irreplaceable, and replace them with new ones. Thus, the modern nation-state could not have been born without the printing press, which disrupted the institutions that preceded it.

Similarly, the Internet is a printing press on steroids, and is already overturning the foundations of nation-states and opens the door to new forms of governance, as we shall see throughout the blog and the book.

Predicting the future

Now that we've laid down some universal historical principles, we're going to use them to try and predict the future of nation-states in broad terms, and how they'll react to the profound disruption created by the Internet and globalization at their very foundations.

This will be the subject of (many) future articles… stay tuned !

Thirty Years’ War. Roughly speaking, even if, according to alliances and counter-alliances, there were Catholics in the Protestant camp, and Protestants in the Catholic camp!

Outram, Quentin (2002). "The demographic impact of early modern warfare." Social Science History, and Parker, Geoffrey (2008). "Crisis and Catastrophe: The global crisis of the seventeenth century reconsidered". American Historical Review

It is estimated that between 7 and 17 million people died from the direct and indirect causes of the religious wars between Catholics and Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries - "The Thirty Years War (1618-48)", Matthew White, Necrometrics, 2012

In its two contemporary forms, Lutheranism and Calvinism

More than twenty wars linked to the spread of Protestantism took place before the 30 Years' War - and the 30 Years' War itself was part of a longer cycle called... the 80 Years' War.

The doctrine of papal infallibility was formally defined only at the first Vatican Council in 1870, but belief in it predates that council and is based on Jesus' promises to Peter (Mat 16:16-20; Luke 22:32)," Vatican I, Dei Filius ch. 3 ¶ 1 and Pastor Aeternus ch. 4 ¶ 5. Vatican II, Lumen gentium § 25 ¶ 3. 1983 Code of Canon Law 749 § 1."

To take just one of thousands of examples, when Prussia took Alsace-Lorraine from France in 1870, it undertook a lengthy process to make the region's inhabitants feel German and no longer French, and when France reclaimed the region in 1918, it did the opposite.

Jean Meyer, La France moderne, collection "Histoire de France", 1985, p. 291.

Peter H. Wilson, Absolutism in central Europe, 2000

"The Cult of the Nation in France: Inventing Nationalism, 1680-1800", David A. Bell, 2003

"Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism”, Benedict Anderson, 1983

There are other examples in history of attachment to structures and communities broader than just the direct community around us: notably attachment to a religion that transcends borders - the Crusades were carried out by individuals from all over Europe whose main commonality was being Christian - attachment to a lord, a king, an emperor and the structure he represents, attachment to an Empire, etc. But the notion of patriotism as attachment to a homeland is a recent invention.

One example among thousands : “The barons who imposed Magna Carta on John Plantagenet did not speak ‘English,’ and had no conception of themselves as ‘Englishmen,’ but they were firmly defined as early patriots in the classrooms of the United Kingdom 700 years later“ - "Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism”, Benedict Anderson, 1983

See the 2 footnotes above

In Japan, for example, the Ainu, an indigenous people of northern Japan, have their own distinct language and culture. The Okinawans, like the inhabitants of the Okinawa archipelago in southern Japan. In France, some regions still have a lively local culture, often accompanied by a regional language that is still spoken, even if often less widely than before, such as Brittany, the Basque Country, Corsica and Alsace, not to mention the French overseas departments and territories.

Whether having several languages and/or religions in a state is a constitutive fact of several nations, rather than one, is a matter of debate among specialists. However, it can at least be argued that the state of a population speaking several languages is at least a little less united than the state of a population speaking one language. For example, Belgium was without a government for 194 days in 2007-2008, 541 days in 2010-2011, and... 652 days in 2019-2020, mainly due to disagreements between the Walloons (native French speakers) and the Flemish (native Dutch speakers) - an absolute world record. And of course, Lebanon experienced a bloody civil war from 1975 to 1990.

Even if, of course, these two wars had factors other than the mere existence of nation-states.

"The Guns of August", Barbara W. Tuchman, 1962, and "The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914", Margaret MacMillan, 2013

"The Cambridge History of the First World War", Jay Winter, 2014, and "The Second World War", Spencer C. Tucker, 2003

See the article about Napoleonic Wars

(Reposting here from 1729) Fantastic article! It's good that you cite David A. Bell: most French people don't know that 100 years ago, most "French" didn't speak French. The French language only started to spread among the lower classes with 1/ free mandatory education (Jules Ferry Laws, 1881 & 1882) and 2/ forced conscription during World War I + mixed combat units with soldiers from all over France (to avoid having soldiers only speaking their local language in a unit).

"as the majority of books were printed in this language, it spread throughout the country much faster and farther than the others.": I think this was only true among the minority of literate people. Even for them, it took time for French to displace Latin as the main literary language: "Even during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, students at the Sorbonne who were caught speaking French on university grounds—or in the surrounding Latin Quarter—were castigated and risked expulsion from the university. Indeed, the Sorbonne's famed Latin Quarter is believed to have earned its sobriquet precisely because it remained a sanctuary for the language long after the waning of Latin—and an ivory tower of sorts—where only Latin was tolerated as a spoken language. Even René Descartes (1596-1659), the father of Cartesian logic and French rationalism was driven to apologize for having dared use vernacular French—as opposed to his times' hallowed and learned Latin—when writing his famous treatise, Discours de la Méthode, close to a century after Du Bellay's Déffence." (source: https://www.meforum.org/3066/does-anyone-speak-arabic )