10 Principles of History for predicting the future (1/2)

To better predict how nation-states will be disrupted by the Internet and globalization

"What did you learn from studying history? Have you learned more about human nature than the man in the street can learn without so much as opening a book?"

Will and Ariel Durant

To this bold question1 , I answer :

"As to methods there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods.

The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble."

Harrington Emerson

For those who know how to observe, history is indeed rich in lessons about the principles of human nature.

And by learning these principles, we can anticipate the methods that will be used by those in power, and predict, in broad strokes, their behavior.

Which is exactly what we'll be doing in this blog (and in my forthcoming book): trying to predict the future of nation-states, and how they'll react to the disruptions of the Internet and globalization, based on these principles.

So, before delving into the heart of this Substack, it's important to lay the foundations by demonstrating these principles.

To do this, we need to go back a little further...

The Roman Empire and the birth of serfdom

The year is 297. Emperor Diocletian was completing his reforms: what remained of the institutions of the Roman Republic disappeared, and the Roman Empire was transformed into a true absolute monarchy. To achieve this, he created the largest government the Empire had ever known, with 35,000 civil servants - where 1st Emperor Augustus needed only a few hundred2 - and expanded the army until one man in 15 was enrolled3.

This was costly, and Diocletian needed to bring money into the coffers: so he reformed the tax system, and above all raised the rates. And to collect all this money, he took care to hire a large number of tax collectors from among the new civil servants he employed.

What were the results of this reform? As historians Will and Ariel Durant tell us4 :

"Taxation rose to such heights that men lost incentive to work or earn, and an erosive contest began between lawyers finding devices to evade taxes and lawyers formulating laws to prevent evasion.

Thousands of Romans, to escape the tax gatherer, fled over the frontiers to seek refuge among the barbarians. Seeking to check this elusive mobility, and to facilitate regulation and taxation, the government issued decrees binding the peasant to his field and the worker to his shop until all his debts and taxes had been paid. In this and other ways medieval serfdom began5 ."

Here we have the example of a government which, faced with the problem of a population fleeing excessive taxation, ends up attaching them legally to the territory in order to better control them, greatly reducing their freedoms in the process... to the point, in this case, of starting a system of quasi-slavery that lasted for over a thousand years6 .

This was neither the first time, nor the last, that a government felt obliged to reduce the mobility and freedoms of its population in order to control it better, even in more contemporary times, as we shall see.

1st principle

1st principle to be learned from history : The power of governments is based on the immobility of their subjects.

And when a population tends to escape their control and thus diminish their tax base and workforce, many governments are tempted to re-establish control by tying this population to their territory, by various means, including the most extreme. These means always reduce the freedom of their subjects.

For a concept to be called a "principle", it must be demonstrated that its consequences have been seen many times before in history.

Other historical examples of this principle include the maximum wage, set at its pre-Black Death level, in the Worker's Ordinance in 13497 (to prevent peasants from leaving their lord to work for another, higher bidding lord), the 1712 edict of the Chinese emperor K'ang-hsi declaring that his government "will ask foreign governments to have Chinese who have been abroad repatriated so that they can be executed”8 , the Iron Curtain9 and the Berlin Wall10 (the USSR and East Germany prevented its citizens from fleeing the country by any means, including shooting at them), US taxation on nationality rather than residence (Americans have to file a US tax form even if they live abroad, one of the very few countries to do so, as discussed in detail in this article), exit-taxes which try to dissuade entrepreneurs from leaving for greener pastures11 .

And we'll see that the Internet now makes the task of governments both more urgent, and far more complicated.

Let's fast-forward a few years to a slightly less ancient era.

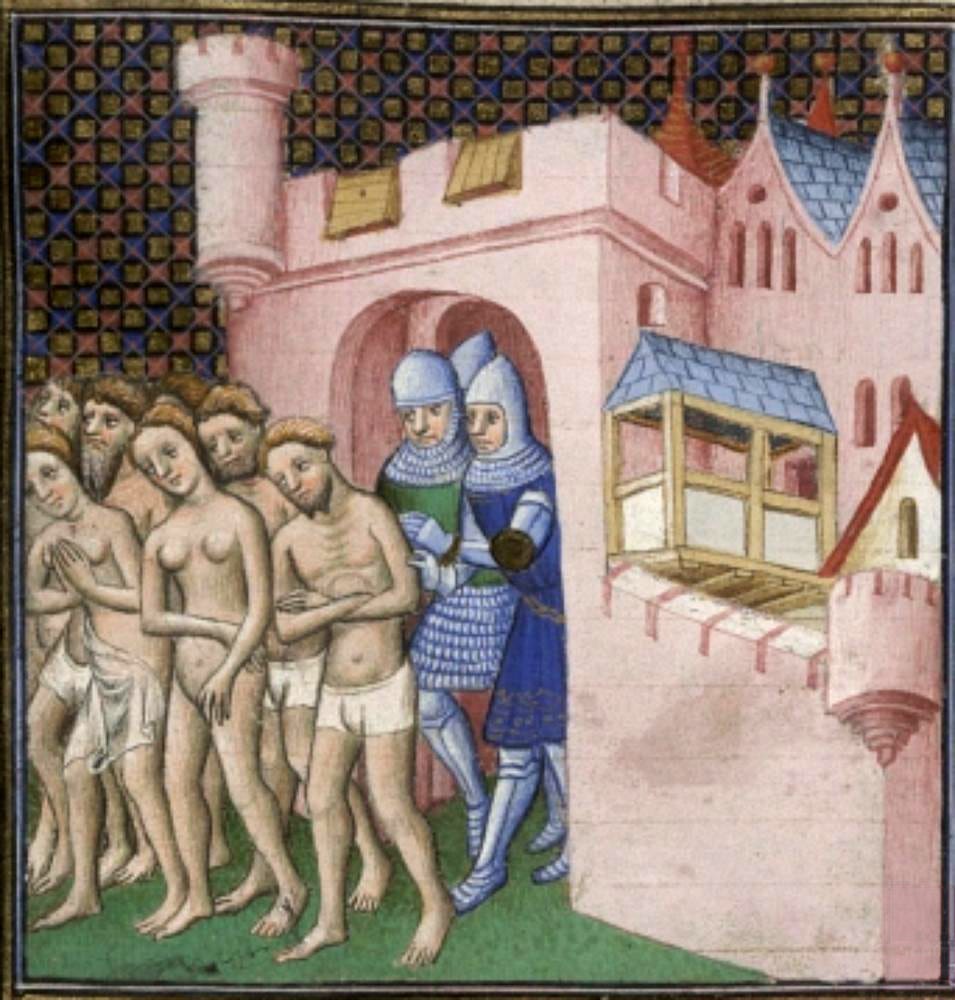

The crusade against the Cathars

Throughout the 12th century, the Catholic Church was concerned about the rise of Catharism, which it saw as a heresy undermining the "true" Christian religion, as well as feudal society.

It tried various more or less diplomatic means to curb the phenomenon, but given its growing power and the fact that more and more lords were converting, in 1208 Pope Innocent III declared a crusade against them, the very first to take place in Western Europe.

Many Catholic nobles joined in - often more out of greed than religious purity - and a few decades later, this "heresy" was destroyed.

How the printing press disrupted the Catholic Church

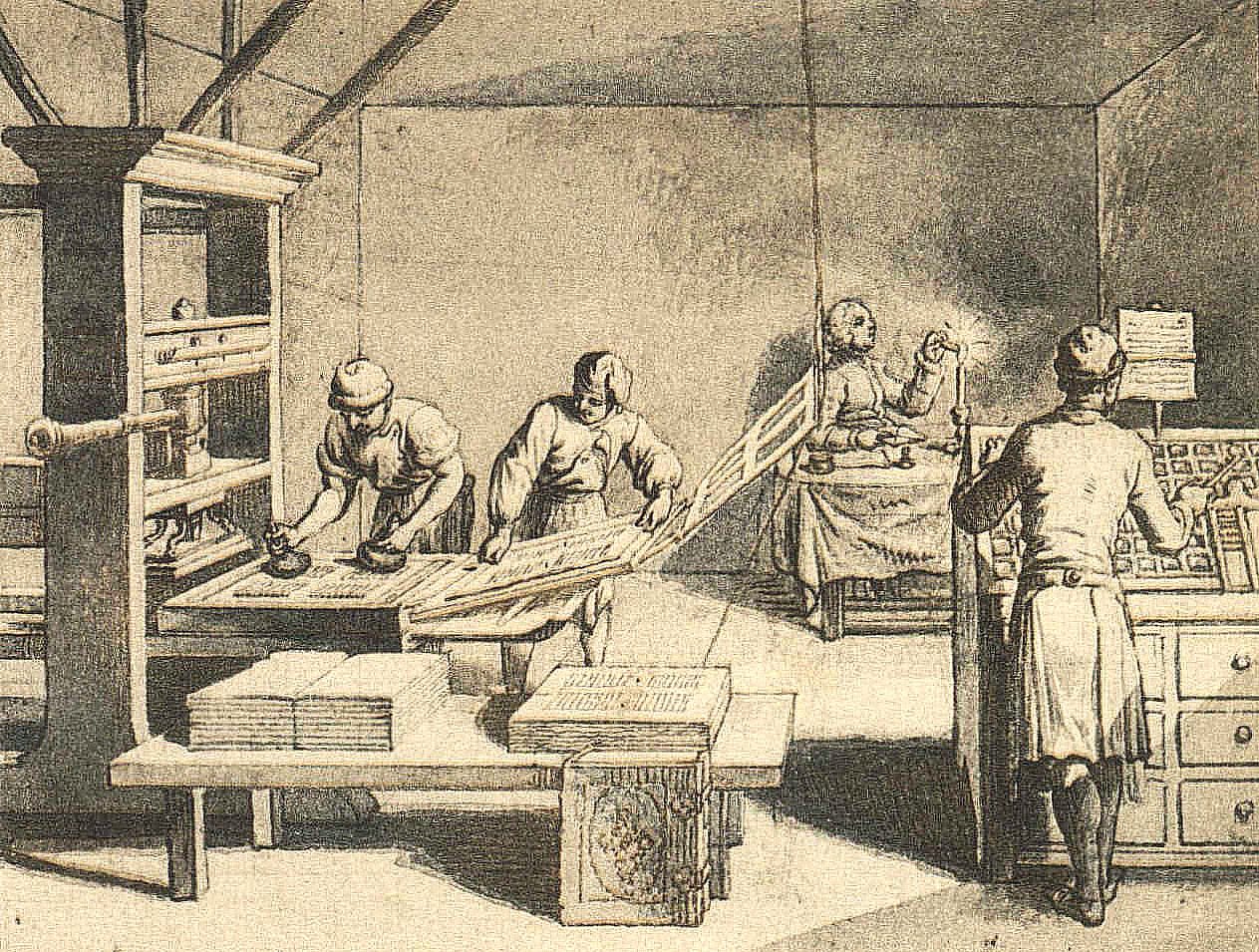

Until 1440, when the printing press was invented, the solution for suppressing any attempt to revolt against the Catholic Church was simple: send in the inquisitors, burn the heretics and their writings at the same time, declare a possible crusade if the movement was already well underway, and presto! The "revolution" was nipped in the bud, sight unseen.

And when, by some miracle, the Church couldn't completely stop a movement (often because it was too small to really threaten her), it easily managed to confine it to a very small section of the population, in a limited geographical area.

Numerous "proto-Protestant" movements were thus halted or severely curbed, such as the Petrobrusians12 , the Henricians13 , the Waldensian movement14 , the Lollards15 , the Friends of God16 , the Hussite Church17 , and so on.

But once the printing press had been invented and had had time to spread, this strategy became obsolete, and it was only a matter of time before a movement could spread so widely as to become unstoppable: this was Protestantism.

Protestantism was helped to spread by printing in two major ways:

By greatly reducing the cost of access to the Bible, and by facilitating the distribution of the Bible in the local language rather than in Latin, this enabled more people to discover Christian religious texts at source, and to see that there was a discrepancy between what they said and the Catholic Church's interpretation of them.

By spreading the ideas of Protestantism so rapidly throughout Europe, that in just a few months it became impossible for the Church to stop its spread. The movement was thus initiated in 1517 by Martin Luther, whose 95 theses criticizing the Catholic Church were so rapidly disseminated throughout Europe that his friend Friedrich Myconius later wrote: "scarcely fourteen days had passed when these propositions were already known throughout Germany, and in four weeks almost all Christendom was familiar with them".

Martin Luther wrote 6 months later: "It is a mystery to me that my theses... have spread to so many places. They were intended exclusively for our academic circle here".

The Church used its usual technique in such cases, excommunicating Martin Luther in 1521 and attempting to condemn him to the stake, but this was not enough: over 1.5 million of Luther's pamphlets were printed in the first decade of the Reformation, contributing dramatically to the spread of his ideas18 .

Seeing the extent to which this technology was undermining its authority, the Church tried to control the press, forcing Catholic printers to seek permission from ecclesiastical superiors before printing any religious work, and prohibiting the anonymous printing of texts at the Council of Trent in 1546. It further reinforced this strategy by creating the List of Prohibited Books in 1559, which contained thousands of books, many of them Protestant.

But it was all in vain: Protestantism continued to spread, and in less than 30 years cut Europe in two, in a division that remains predominant more than 4 centuries later.

This so diminished the Church's power that it has never recovered: whatever its influence today, it is a shadow of its former self compared to the zenith of its power over 5 centuries ago.

And today, just under 40% of the world's Christians are Protestants19 .

2nd Principle

2nd principle to be learned from history: a cheap, uncensored content distribution technology is highly disruptive to the powers that be. It has already proved its power to completely overturn an institution that had been in existence for over 1,000 years, and had such a hold on society that it seemed indestructible.

Another example of this principle in history is, of course, the Internet, whose disruption we'll be taking a closer look in later articles.

3rd Principle

3rd principle to be learned from history: When a cheap, hard-to-censor communications technology develops and starts spreading points that run counter to that of the authorities, the authorities in power try to control it and institute mechanisms to tell "good believers" what is true and what is not.

Such were the Church's attempts to control the use of the printing press, and the books placed on the Index.Other examples of this principle in history: the blacklist of banned websites in Russia (and other countries), the Chinese "Great Firewall", the American "Disinformation Governance Board", nicknamed the "Ministry of Truth", designed to "fight disinformation", and stillborn in 202220 .

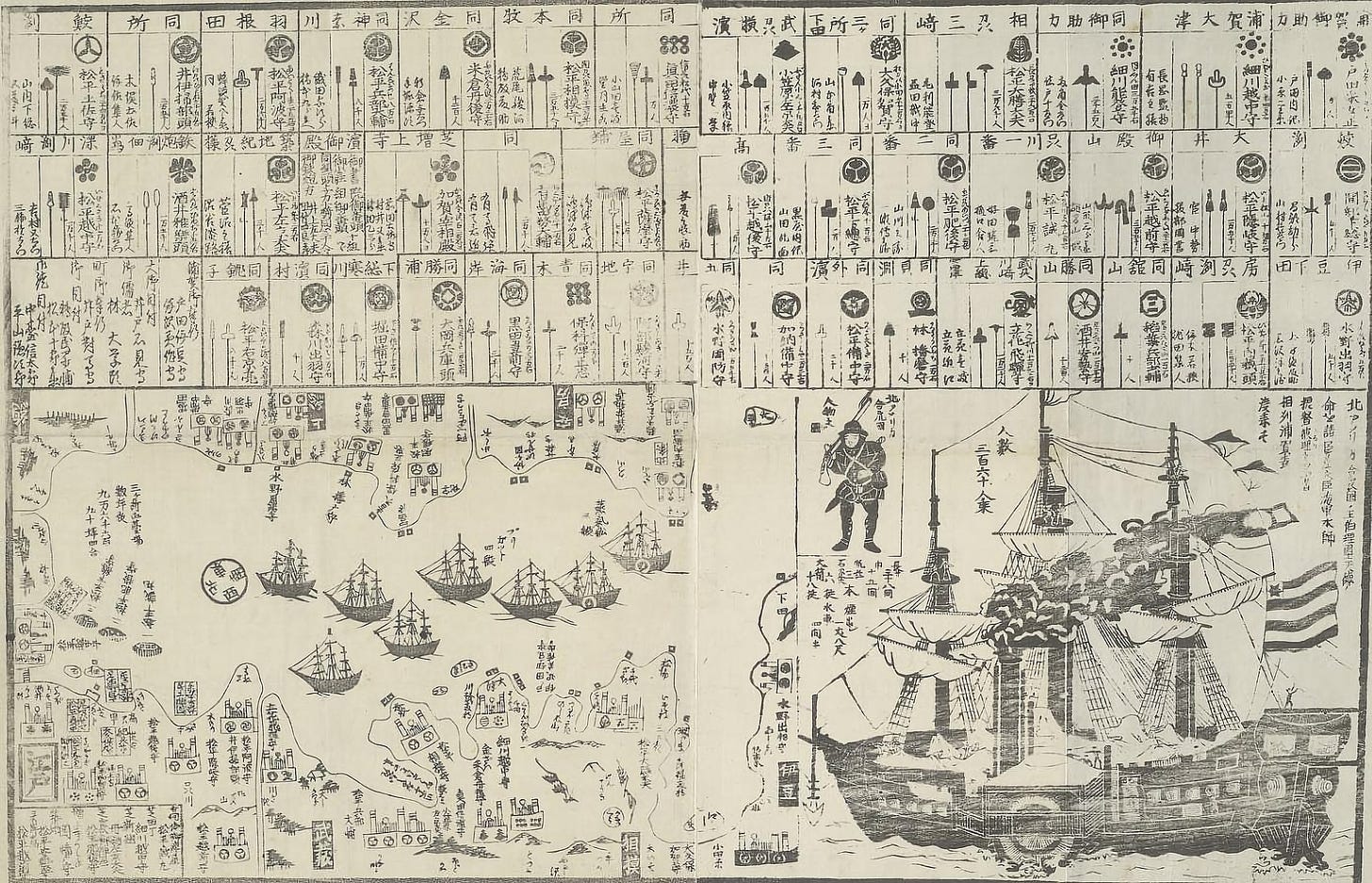

How to win in order to lose: the example of the Ottoman Empire

In the 15th century, the Ottoman Empire was a power that shook the whole of Europe.

It captured Constantinople in 1453, putting an end to the last vestiges of the Roman Empire after more than 2,000 years of rule.

What's less well known is that Sultan Mehmed II didn't want to stop there: after taking the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, he wanted to do the same with the former capital of the Western Roman Empire, and above all the seat of the papacy: Rome.

In 1480, when the Empire already controlled all of Greece and part of the Balkans, Mehmed sent his admiral Gedik Ahmed Pasha at the head of a 20,000-strong army to invade Italy. They landed in the south and quickly took the town of Otranto. The Ottoman army was now only a few days' march from Rome.

A crusade was declared, and a Christian army was dispatched to retake the city, but failed. The Ottoman army was waiting for reinforcements to continue its conquest and finally take the Eternal City.

Fortunately for the Christian powers of the time, an unexpected stroke of luck occurred: Mehmed II, who was in Turkey at the time, died suddenly, probably poisoned. This triggered a war of succession between his sons, forcing the army in Italy to cancel its plan of conquest and capitulate.

Had it not been for this twist of fate, it's quite possible that Mehmed would have succeeded in conquering Rome, which would have profoundly changed the history of Europe - and the world.

This shows just how powerful the Ottoman Empire was at the time. A few decades later, in 1521, Belgrade succumbed to the Empire's assaults, and the Balkans began to be incorporated into it.

And yet, 2 centuries later, the balance of power was completely reversed, to the extent that the siege of Vienna in 1683 - which was a hard-fought victory for the Christian camp - was the very last time in history that a Muslim state seriously threatened Europe.

From then on, it was a slow decline for the Ottoman Empire: in 1699, after several major military defeats, it signed the Treaty of Karlowitz, which took away virtually all its territories in Central Europe, and suffered a long succession of territorial losses, until it reached the present-day Turkey.

But what has caused this decline? What are the factors behind it?

We're not the only ones to wonder about this: as far back as 1732, Ottoman historian İbrahim Müteferrika posed this question in his book Rational Basis for the Politics of Nations:

"Why have Christian nations, which were so weak in the past compared to Muslim nations, begun to dominate so much land in modern times and even defeat the once-victorious Ottoman armies21 ?"

There were several, but the main one is that the Ottoman Empire fell considerably behind in the scientific and economic, and therefore military, fields, and the main reason for this is that no printing works in Arabic characters22 were established for 2 centuries, from 151523 to 172724, then after a short period of production between 1727 and 1742 (thanks to İbrahim Müteferrika cited above), until the early 19th century25 .

There were many reasons for this ban: bans by the sultans26, opposition from religious authorities - who considered calligraphy a divine art - and scribes - who, like cabs faced with Uber, did not want to lose their monopoly on book production - fear of the influence of foreign Christian powers, who were behind the invention of this machine, apathy on the part of intellectual and economic elites who saw no point in it, etc.27 .

Thus, barely 16 years after being granted permission to print, İbrahim Müteferrika had his privilege withdrawn in 1743, under pressure from copyists and scribes.

The Ottoman Empire was thus unable to benefit for centuries from the technology for distributing ideas that was so important in shaping the modern world, to the extent that it never caught up: even today, Turkey, the Empire's heir, lags behind most European countries in terms of economic development28 .

4th Principle

4th principle to be learned from history: States that win temporarily by succeeding in banning or stifling a technology lose in the long term because they do not benefit from the fruits of that technology, to the extent that centuries later, the consequences of the accumulated backwardness are still visible.

Another example of this principle in history: the Edo period Japan, which successfully expelled, killed or converted all Christians between 1612 and 1660, and isolated itself almost completely from the rest of the world, forbidding all Japanese to travel outside Japan from 1635, banning ships capable of sailing the oceans, restricting foreign trade to the Chinese and Dutch (who could only anchor in a single port), and freezing many technologies, including military ones, as they were at the beginning of the 17th century.

This worked perfectly until 1853, when the United States sent a squadron of warships, commanded by Matthew Perry, to force Japan to open up to trade once again.

Japan's military technologies and doctrines were so far behind those of the West, that the political powers of the day had no choice but to submit, and open the country up to international trade once again.

However, the Japanese were quick to realize that they had fallen behind the West, and from 1868 onwards undertook a rapid, large-scale reform of their country to bring it up to Western standards, industrializing it within a few decades29, and even succeeding in beating Russia in a naval battle30 in 1905, winning the very first battle between an Asian and a Western country in the modern era. It is therefore sometimes possible for certain countries to catch up, if they really want to and are prepared to make the necessary sacrifices.

But Japan's backwardness was bound to lead it to lose its isolationist battle after a while: it was inescapable.

The Japanese were lucky that the first foreign force to force them to reopen to the world wanted to trade: they would have had great difficulty repelling the invasion of a Western force with weapons and doctrines from 1850, defending themselves with weapons and doctrines from 1620.

Another power disrupted by a new technology

The other great power of the Middle Ages was the feudal power.

It was a highly hierarchical power structure, with the king at the top of the pyramid, followed by the great lords (dukes, barons...), followed by smaller lords (counts), followed by knights.

The lords' power was expressed and protected by the size of their territory, and the defensive capacity of their castles.

And, in the Middle Ages, the technologies of defense were superior to those of attack, since it was easier, all things being equal, to build a castle than to take it.

The king, theoretically the most powerful of the lords31, could raise a large army by asking his vassals to contribute to his own, and could in theory take any castle in his territory.

But while he could take any castle, he was limited in his ability to take many.

In other words, he could take 1, 2 or 3, but not 10, 20 or 30. That would have taken too long, occupied too many soldiers for too long, depleted the treasury and devastated the country's economy.

This forced the king to negotiate with the lords, and gave the latter true independence over their territory.

One technology profoundly disrupted this state of affairs: gunpowder.

It arrived in Europe in the 14th century, in the primitive form of "bombardes" hardly better than the catapults and trebuchets of the time, but from the 15th century onwards, its refinement led to the appearance of real cannons and harquebuses, and this completely changed the balance of power.

With the advent of the harquebus, suddenly a quickly trained peasant could easily kill a nobleman specialized in warfare with 20 years of experience, on a horse and in extremely expensive full armor and virtually unbreakable by conventional weapons32.

And with cannons, attack technology was suddenly superior to defense. It was now easier to take a castle than to build it, and this made all lords vulnerable to a modern army.

After the advent of the cannon and the harquebus, the winner in violent conflicts was no longer the one who built the most impregnable castle, or had the army with the most richly equipped specialists in violence: the winner was the one who could most easily mass-equip an army with rifles and cannons.

This led to a gradual erosion of the political power of local lords, in favor of a centralization of power by the monarch, better able to finance a powerful army.

5th Principle

5th principle to be learned from history: A reversal of the balance of power between attack and defense technologies is highly disruptive to the powers that be33.

Another example of this principle in history: the machine gun temporarily gave a strong advantage to defense over attack, and largely explains why World War 1 was initially a trench war, before innovations such as the tank once again gave the advantage to attack.

This invention greatly disrupted nation-states and their generals at the start of the Great War, as they had not integrated its disruptive effects on the battlefield: many generals, trained at a time when cavalry charges could still have a significant effect, took a long time to understand that most of their strategies and tactics no longer worked.

This cost the lives of millions of soldiers sent to the slaughter by commanders stubbornly sending waves of infantry, often advancing in the open over vast expanses of terrain, exposed to the devastating fire of enemy machine guns - 19th century strategies ill-suited to the fight against this new weapon.

We shall see later that this is a very important point, and that the Internet is a major catalyst for this inversion today, along with other technologies (3D printing of weapons, drones, and above all cryptography...).

The modern equivalent of the castle is the nation-state, and the Internet is its gunpowder.

To be continued…

In the next article, we'll look at the next 5 principles that history teaches us to try and predict the future of nation-states!

In the meantime, if you see any errors in these principles, please say so in the comments! I'll be relying on these principles throughout my book (and in my Substack articles), so it's very important that they're as true and factual as possible.

From a couple of historians who had no doubts about the answer to give

"Rome: Decline and Fall? Part II: Institutions", Bret Deveraux, 2022, and Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society

Southern, 159; Treadgold, 112-1

The Lessons of History, Will and Ariel Durant. This book, as well as "The Sovereign Individual" by James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg, inspired me to look for universal historical principles

Serfdom was abolished in France in the 14th century, in Great Britain in the 16th century, and before the 1st half of the 19th century in most Western European countries.

The Black Death killed more than a third of the English population in 1348. As labor became scarce, some lords promised higher wages to peasants from neighboring fiefs, causing large-scale migration. To stem the tide and keep serfs in their original fiefdoms, the English Parliament forbade offering and accepting higher wages than before 1348. One of the punishments for peasants who transgressed this law was to have their skin branded with their lord's mark.

"Imagined Communities", Benedict Anderson, 1983

They were put in place to stem an exponential flow of emigrants: between 1945 and 1950, 15 million people emigrated from the Eastern bloc to the West - Böcker, Anita (1998), Regulation of Migration: International Experience.

Between 1949 and 1961, 2.5 million East Germans fled to West Germany - Gedmin, Jeffrey (1992). "The Dilemma of Legitimacy. The hidden hand: Gorbachev and the collapse of East Germany. After the Wall was built, only 5,000 people were able to flee from East to West between 1961 and 1989.

See, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in "Crandall v. State of Nevada, 73 U.S. 35". State of Nevada, 73 U.S. 35" in 1867 (yes, it's not new), which held that "Since all citizens have the right to move freely, a State cannot impose taxes that impede their ability to leave [from one state of the United States to another]. "A legal study into the EU's approach towards exit taxation", Patricia Zakrzewska, 2020.

Founded by Peter of Bruys in France in the early 12th century, who was either burned at the stake or killed by a hostile crowd, depending on the source.

Movement founded at the very beginning of the 12th century by Henry of Lausanne, who was condemned for heresy and died in prison.

Born in France in the 12th century, persecuted by the Church to the point of almost disappearing, before merging with Protestantism.

Movement born in England at the end of the 14th century, and repressed until it almost disappeared in 1440.

Created in Switzerland around the middle of the 14th century, it was brought to a halt when its principal instigators were arrested and burned for heresy.

Initiated in the early 15th century by Jean Hus, condemned for heresy and burned in 1415. The Hussites held sway over part of the Czech lands for another 2 centuries.

"How Luther went viral", The Economist, 2011

"Christian Traditions", Pew Research Center, 2011, "Encyclopedia of Protestantism: 4-volume Set", 2004

Announced on April 27, 2022, and "paused" on May 18 of the same year. Despite its short lifespan, this commission demonstrates the US government's desire to control the Internet. See this article for more info.

For example, while the Ottoman navy had suffered no major defeats against European navies from the 15th century to 1571, it lost the important battle of Lepanto that year, with between 20 and 30,000 men and 187 ships lost, against between 7,500 and 10,000 men and 13 ships for the Christian army, and that was only the beginning: in 1616, at the battle of Cape Celidona, the Ottoman navy lost 33 ships and 3,200 men, compared with only 34 dead and no ships lost for the Spanish navy, thanks to European technological advances - Andrew Wheatcroft, "Infidels: A History of the Conflict between Christendom and Islam", 2004.

At the time, Turkish was written in the Arabic alphabet

Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453-1924, Phillip Mansel.

Printing presses did exist in the Empire during this period, but they were run by Jews and Christians, and did not print books in the Arabic alphabet.

Gábor Ágoston; Bruce Alan Masters (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire

For example, in 1515, a decree issued by Selim I threatened anyone involved in the science of printing with death. This death sentence did not last, but it shows the tone of the times: this was no laughing matter.

See "Age of Invention: Did the Ottomans Ban Print?" by Anton Howes, 2021, for further research on the subject.

In 2020, Turkey is 102th in nominal GDP per capita (out of 216 countries), and 48th in nominal GDP per capita in purchasing power parity, while the European Union would be in 32th place if it were considered as a single country.

This is the backdrop for the film The Last of the Samurai, starring Tom Cruise, which takes many liberties with historical reality, but has the merit of showing a little of the atmosphere between traditionalist and modernist currents when Japan decided to modernize.

Even if, depending on the place and the time, this was not necessarily true.

With the exception of the crossbow, which took a long time to reload and required more training than the harquebus.

This is one of the major theses of The Sovereign Individual by James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg, who has strongly developed this theme, and is a great source of inspiration.

This was so interesting — I really appreciated the in-depth examples and got a good refresher on my history! When the Americans arrived in Japan in 1850, what was it that made the Japanese decide they had to open up again? Anything specific?

Kudos for the researches to compile your forthcoming book.

Just to say: the Catholic Church, and the substantive Church as an institution should be gramatically defined as "it" not "she".