Will Nation-States Game The System with Cartels ?

Inside the OECD's two pillars for combating international tax optimization

Note : This article is the 5th in a series on over-legislating a a path that more and more nation-states are taking in an attempt to emasculate the disruptions that threaten them.

Here is the first 4 articles in the series :

As we saw in a long 14 parts series that started this blog, the Internet and globalization are disrupting nation-states.

Now, as one of the major disruptions threatening them is the exacerbated tax competition enabled by the Internet and globalization, an obvious solution for nation-states is to try and form cartels to combat this.

Will it work? That's what we'll examine in detail in this article.

What is a cartel ?

A cartel is an agreement between different companies, often in the same industry, to artificially limit competition.

This often takes the form of artificial price fixing, by sharing markets, coordinating production levels or setting minimum prices.

This allows these companies to circumvent free market mechanisms, always to the detriment of the consumer.

This practice is therefore prohibited, as a free, competitive market encourages companies to innovate, improve product quality and reduce costs. Conversely, cartels reduce this competitive pressure, creating a rent that almost systematically leads to higher prices, lower quality and less innovation.

This means a colossal loss for consumers.

For example, in France, three major mobile operators - SFR, Orange and Bouygues Telecom - colluded between 1997 and 2003 to reduce competition between them, resulting in an estimated loss of between 1.2 and 1.6 billion euros for consumers1 .

As a result, the three companies were fined 58 million euros for Bouygues, 220 million for SFR, and 256 million for Orange by the French Competition Authority2 .

National authorities are not kidding when they spot cartels operating on their territory. And yet, there are examples of international cartels, such as OPEC, which seem to operate with impunity.

From national illegality to international legality

What is OPEC? Imagine a bunch of friends playing on the same playing field, and realizing that they all have one precious commodity in common: oil. In 1960, these friends, who at the time were five oil-producing countries (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela), decided to join forces and create a team, called OPEC. Their main objective? To control the price of their precious oil, by deciding together how much they will produce and at what price they will sell it.

Since then, other countries have joined the organization, then left, then sometimes rejoined again (sometimes only to leave again!). At the time of writing, OPEC comprises 13 countries, accounting for 30% of world production and 80% of proven reserves3 .

Since its creation, OPEC has had a considerable impact on world oil markets, often influencing prices upwards or downwards. Sometimes, as in the 1970s, it has even managed to provoke oil shocks, driving prices up dramatically.

And it's all completely legal.

How is this possible? The answer is simple: competition law applies mainly within a country's borders. Organizations like OPEC, which are international cartels, are not governed by a supranational authority that could dissolve them.

When nation-states form cartels to distort competition

So here we have an example of nation-states also using globalization to grant themselves rights that they deny to people and entities operating on their own territory!

And we have seen, and will see later, that this is not the only example of a double standard, with many governments allowing themselves practices that they have banned in their own countries.

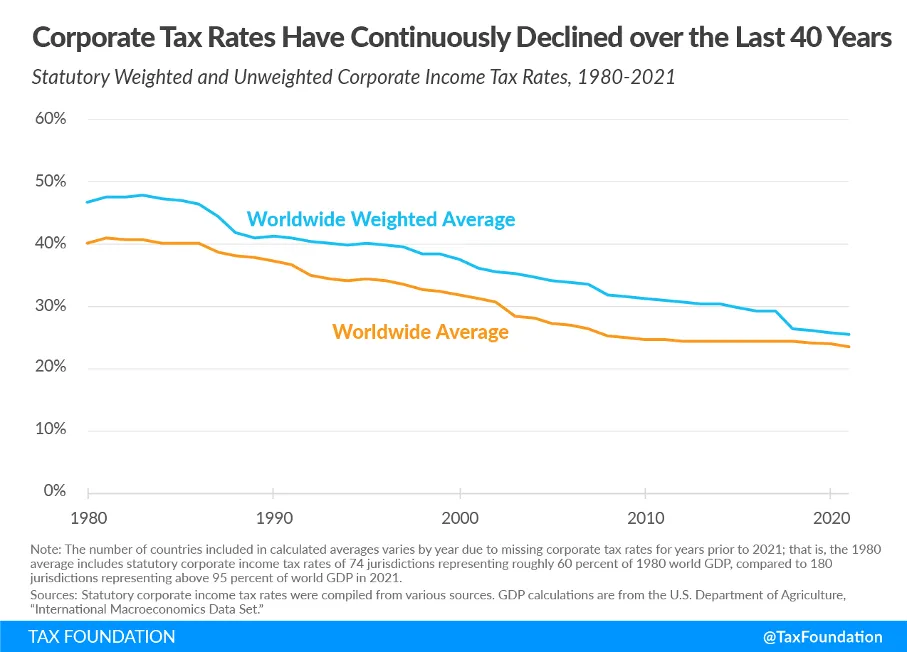

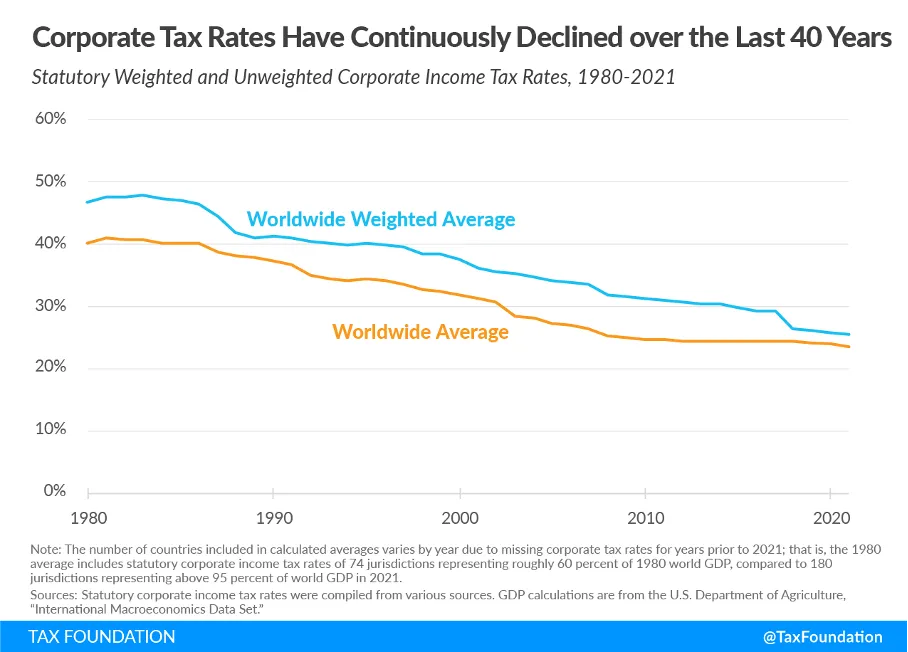

As I showed in “The Worst Moment: The Growing Difficulty Of Nation-States To Raise Taxes”, since the 1980s, governments have been subject to intense tax competition linked to globalization and accelerated by the Internet, forcing them to lower their real and top corporate and income tax rates.

The main reason is simple: as companies and individuals become increasingly mobile, they can more easily choose the jurisdictions that offer them the best conditions.

Like all competition, this competition is healthy, as it forces governments to innovate, improve the quality of their services and reduce their costs. In short, to improve the quality/price ratio of their governance services.

But of course, like all entities facing competition so fierce as to be disruptive, many countries don't see it that way, and are increasingly organizing themselves into cartels to try and limit this competition.

OECD’s 2 Pillars

Among these cartels, the most important at the time of writing is the OECD, which is trying to set up a global minimum tax for companies via two "pillars", in order to combat tax competition:

Pillar 1

Companies with annual sales in excess of €20 billion that make "excess profits" (defined as any profits in excess of 10%) will have to allocate 25% of these excess profits in proportion to the countries where their customers are physically located, regardless of where these companies are actually located.

So, if a company is based in the USA, has annual sales of 25 billion euros, makes 20% profits, and has 50% of its customers in the USA and 10% in France, Great Britain, Germany, Spain and Italy respectively, it will have to pay corporation tax on 6.25% of its profits4 to these five European countries, at a rate of 20% per country, and 6.25% to the USA.

If the agreement works, it is planned to lower the trigger threshold to 10 billion euros in sales seven years after the agreement is implemented.

Pillar 2

Companies with annual sales of over €750 million will have to pay a minimum corporate income tax of 15%, regardless of the official rate in the country where they are located.

If the country in which the parent company is located does not do so, the countries in which the daughter entities are located will be able to tax the difference.

And conversely, if subsidiaries are taxed at less than 15%, the country where the parent company is located will have the right to tax the difference.

How will the 2 pillars evolve?

At the time of writing, 135 jurisdictions have signed up to the OECD agreement and committed to its implementation.

This can clearly be seen as a victory for this cartel, and as a major counterweight to the trends I describe in this book.

However, there are a lot of things that make me think that it's not going to be easy for them:

1. The number of non-signatory jurisdictions

With 135 signatory countries, it's an undeniable success story.

But of course, as there are 195 countries in the world, that means 60 non-signatory countries, which opens up just as many potential loopholes.

And among them... the United States. Republicans are vehemently opposed to the agreement, believing (rightly) that it will diminish U.S. sovereignty, since the government will be less free to set fiscal policy as it sees fit, a right granted only to Congress by the Constitution.

What's more, several studies show that the USA has the most to lose from the implementation of these rules, given that these multinationals are the most represented in the companies affected by these criteria.

A study by a US Senate committee5 , for example, estimated the US tax loss for Pillar 2 alone as follows:

If the rest of the world implements Pillar 2 and not the US, the tax loss will be $122 billion over ten years.

If the United States also implements Pillar 2, the tax loss will be $56.6 billion.

As you can see, in theory, the USA has more to lose by not implementing Pillar 2, if the rest of the world does, because in that case, the countries where subsidiaries of their companies are located will be able to tax any difference between their actual tax rate and the 15%.

However, this does not guarantee that the USA will implement this pillar: it could choose to implement trade retaliation, exert diplomatic pressure, etc.

It remains to be seen what the United States will do, and this will depend in particular on the political party in power at key moments in the implementation of this agreement (the Democrats being more open on the subject), but we can already see that they have an interest in trying to torpedo it.

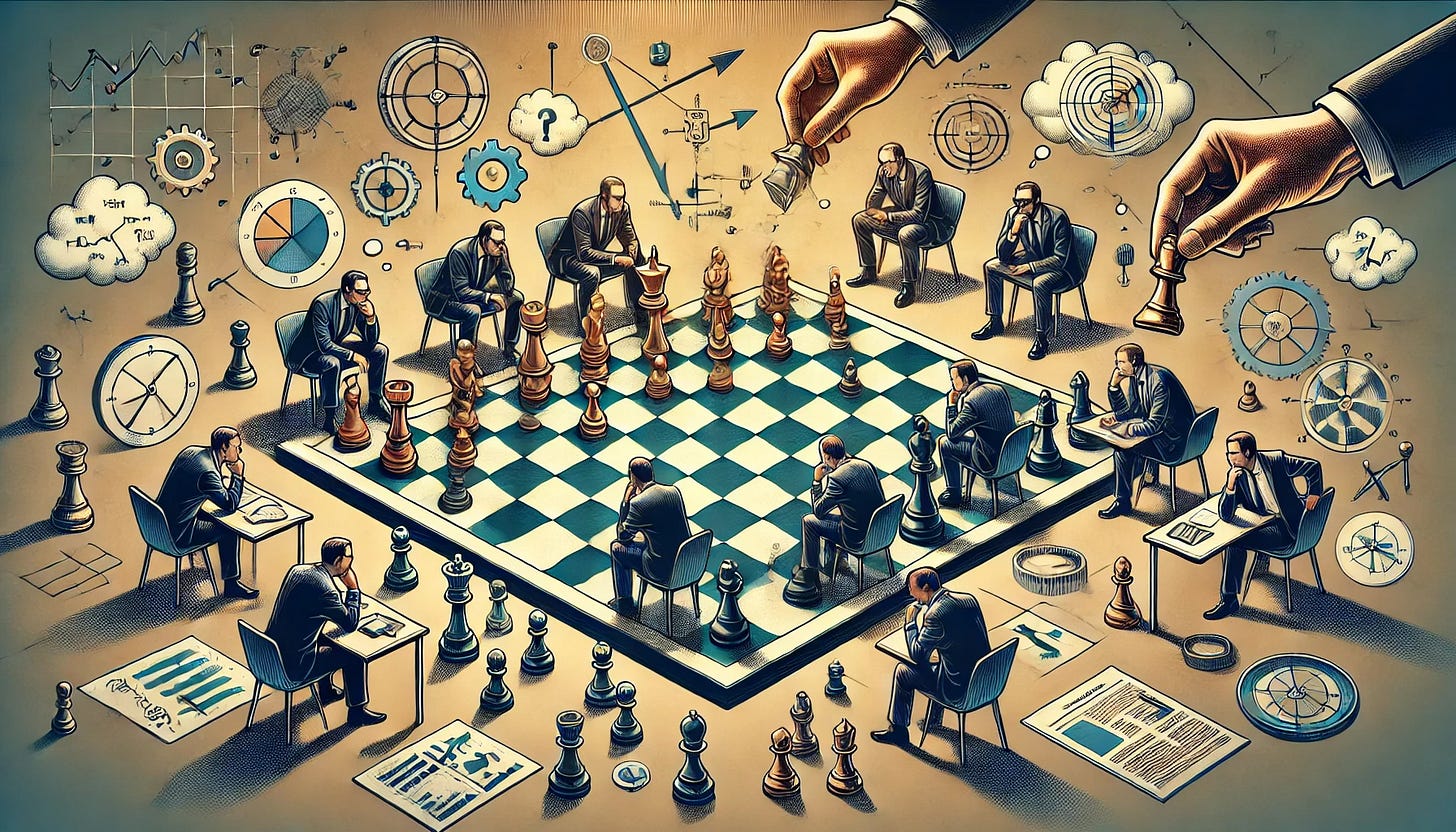

2. What game theory tells us about the OECD strategy's chances of success

Game theory, a scientific discipline, helps decision-makers anticipate the actions of others, define the best strategies to adopt and understand how their decisions will influence the actions of others.

This can lead to more informed and effective decision-making, whether in trade negotiations, policy formulation, resource management or strategic planning.

Game theory, dear readers, is a bit like trying to predict your opponent's next move in chess.

Let's see how it applies to the operation of a cartel.

In a cartel, each member has a choice to make: does he collaborate with the others to keep prices high, or does he betray the cartel to increase his own market share?

If everyone cooperates, everyone wins a little. But if one member betrays the others by selling more products at a lower price, he can earn a lot, while the others lose.

This is what is known in game theory as a "prisoner's dilemma". The problem is that betrayal can be very tempting, and that's where things get complicated.

So, while a cartel may be profitable in the short term, in the long term it tends to prove unstable. Why is this? Because each member has an incentive to "cheat" in order to increase his or her own profits.

Cartels also face other challenges, such as differences in costs and production capacity between members, or changes in market demand.

To maintain cohesion, cartels must therefore put in place control and sanction mechanisms to dissuade their members from cheating, which can be very difficult to achieve, especially in an international context where the application of agreements is complex.

So, while some cartels may operate for decades, as in the case of OPEC, game theory teaches us that they are inherently unstable and often short-lived.

The example of OPEC

And that's exactly what happened with this cartel: the high prices of the 1970s (due to the success of OPEC's policy) prompted many non-OPEC countries to look for new sources of oil. As a result, new non-OPEC reserves were tapped and oil prices began to fall. Seeing this turn of events and deciding that they needed to make short-term profits by selling more oil, many OPEC members chose to leave the cartel.

Saudi Arabia responded by flooding the market with oil, causing prices to plummet, to punish members who had defected, since its production costs were the lowest in the world, and it was less affected by these low prices than the others.

This is an example of behavior that, from the outside, is clearly self-destructive for the cartel.

How the OECD cartel might act

Of the more than one hundred jurisdictions that have signed the agreement, dozens and dozens, if not the majority, will find themselves faced with exactly the same dilemma: they will be tempted to cheat to maximize their revenues.

This cheating will probably not take the form of withdrawing from the agreement, in which case other countries will be able to recover the taxes not collected, but rather of subtle cheating, using loopholes not anticipated by legislators - loopholes in which certain countries have become specialists.

3. Loopholes of the two pillars

Beyond this specific cartel, all regulations are also subject to game theory, since there are always players who have an interest in not being subject to regulations, whether legally or illegally, or both.

Let's look at some of the ways in which companies subject to these two pillars might react.

This attempt by the OECD is far from being the first.

For example, the BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) project was launched in 2013, with the aim of ensuring that companies pay their taxes where they carry out their economic activities and create value, rather than transferring their profits to low-tax countries, by artificially placing their intellectual property there, for example.

This project, adopted by dozens of countries... is now widely regarded as a failure6 .

There are many reasons for this, but the main one is that there are always loopholes, unforeseen situations, and interactions between different treaties and laws that could not have been anticipated.

And motivated individuals and companies will always find flaws in a system, especially when it's complex and international as in this case.

An obvious loophole : Subsidies

For example, an obvious loophole in the new agreement is the question of subsidies. A subsidy is considered as income, which could therefore be taxed at that famous minimum total of 15%, but always at a low percentage compared to the money earned.

So if certain countries wanted to cheat to attract more companies to their soil, they could always offer advantageous subsidies, which would have the practical effect of lowering their tax rate.

A report by the Joint Committee on Taxation of the US Congress thus states in 2023:

"Thus, the effectiveness of the second pillar could be weakened by the introduction of these forms of tax credits by low-tax jurisdictions. The country that introduces them thus preserves its tax-competitive characteristic without visibly having a low tax rate. This could lead to tax credit competition [...] between countries wishing to compete to attract multinational companies. [...] In general, while the second pillar may reduce tax base erosion and profit shifting, it may also increase tax competition on other factors7 ."

In the past, several countries, such as Ireland and Malta, have made a specialty of offering "correct" official corporate tax rates, but with much lower effective tax rates: it is estimated that in Ireland, many multinationals pay a rate of between 2.2% and 4.5% instead of the advertised8 12.5%9 , and while the official Maltese rate is 35%, many companies can claim a tax refund of 6/7e , bringing it down to 5%10 .

It's clear that many countries will take advantage of the inevitable loopholes of this type to offer similar deals11 .

Tax havens stand to benefit the most

What's more, if it's guaranteed that a multinational will be taxed at 15%, why would it choose to move its business to "normal" countries, rather than keep its current structure in tax havens?

These tax havens are not only attractive for their low rates, but also for their very business-friendly regulations, the protection they offer against certain disputes, sometimes their skilled workforce, and so on.

Not to mention the subsidies that these countries could pay to reimburse, in part or in full, the taxes paid.

It is therefore quite possible that this tax increase will primarily benefit... these tax havens, since they will be the first in the chain to be able to "help themselves" (and if they don't, other countries further down the chain, particularly where subsidiaries are located, will).

Some analyses by economic and tax specialists already point in this direction12 , and an exception for real economic substance has been negotiated in both pillars, i.e. the 2 pillars will not apply in full if the company has offices and employees generating real added value in tax havens.

This will encourage multinationals to relocate as many employees as possible to tax havens, accentuating the migration of mobile workers and the disruption of traditional nation-states.

The absence of a physical presence

Pillar 2 can only be activated by the government of the country where the target company or one of its subsidiaries is physically located (Pillar 1 is supposed to apply even in the event of total physical absence, but is, at the time of writing, the pillar whose adoption seems most fragile).

The adoption of Pillar 2 could have the effect of encouraging a number of companies, particularly those that are already natively Internet-based, to physically withdraw altogether from the countries that are the most troublesome in applying the two pillars, which would have a negative effect on employment and the economy.

This will even become increasingly possible for some physical businesses, as virtual reality and augmented reality become more widespread: if these tools enable you to see for yourself whether a particular item of clothing fits you, for example, you won't need to go into a store to try it on and buy it.

It's not at all certain that the expected benefits will be there

In January 2023, the OECD estimated that the additional global income that the world's governments would share thanks to Pillar 2 would amount to $220 billion a year13 .

Then, a year later, the estimate was revised downwards to between $155 billion and $192 billion, a reduction of between 13% and 30%.

Estimating the tax revenues of new measures is notoriously difficult, and many measures that were supposed to bring in big bucks have turned out to be nothing more than damp squibs, as we've seen from a number of examples.

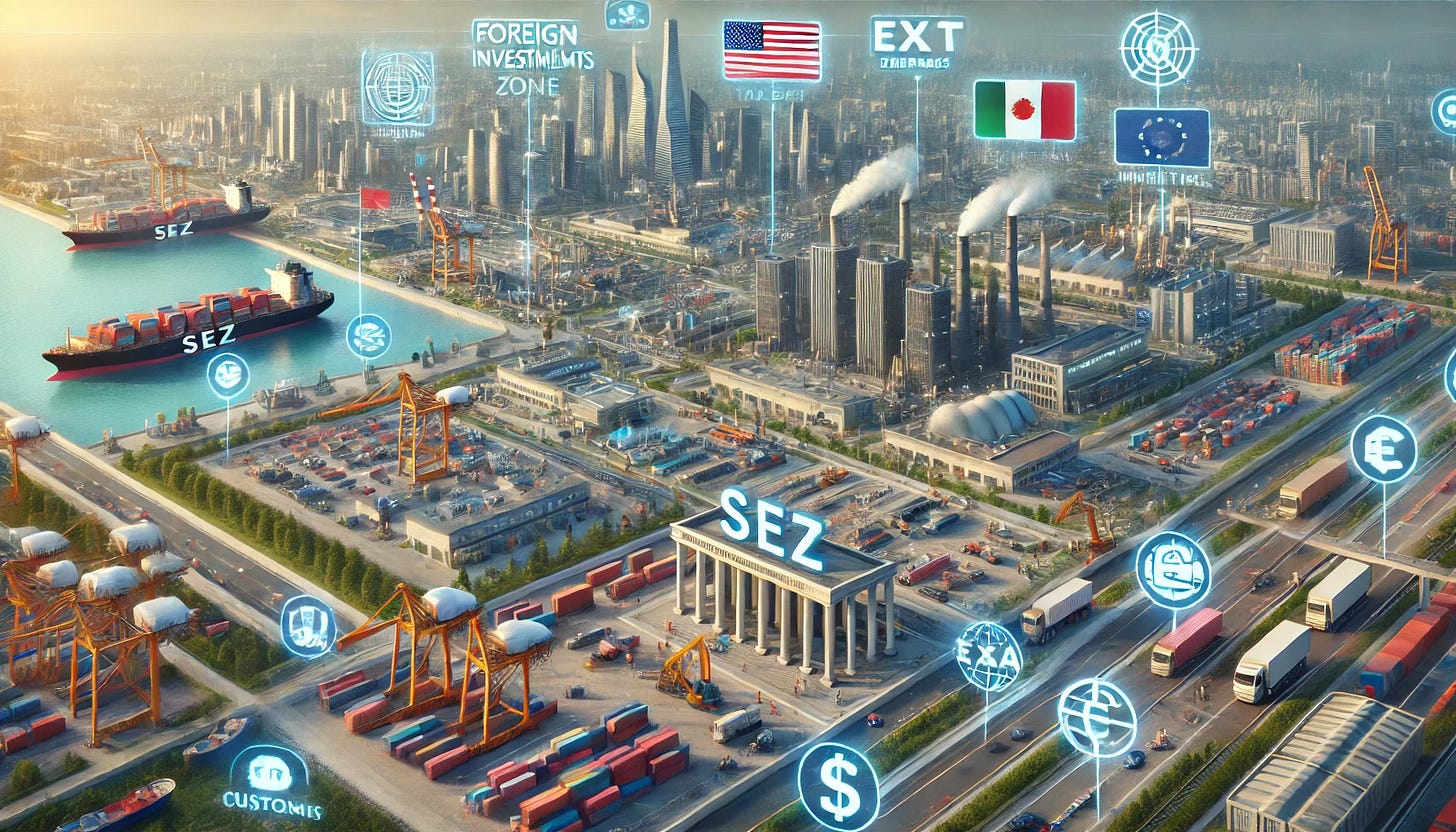

4. Multiplication of jurisdictions within countries

Beyond this, we can observe another trend serving as a counterweight to these international regulations: the multiplication of jurisdictions within countries.

"What do you mean," you might ask, "that a country14 is not a single jurisdiction?"

Well... yes and no.

Because, you see, SEZs have been multiplying for decades.

SEZ? But what is this beast?

A SEZ (Special Economic Zone) is a geographically delimited region within a country, where economic laws differ from those of the rest of the country, with the aim of promoting economic development.

Designed as experimental laboratories to attract foreign investment, boost exports and create jobs, these zones offer benefits such as tax breaks, simplified customs procedures and, in some cases, lighter regulations.

They play an important role in attracting foreign capital, adopting new technologies and modernizing the economy. Historically, SEZs have helped transform entire economies, as in China, where they have driven rapid economic growth and helped millions of people escape poverty and join the global middle class.

By creating SEZs, China experimented with small-scale capitalism, before extending it to other zones, thus promoting the spread of free-market capitalism in a previously centrally planned economy.

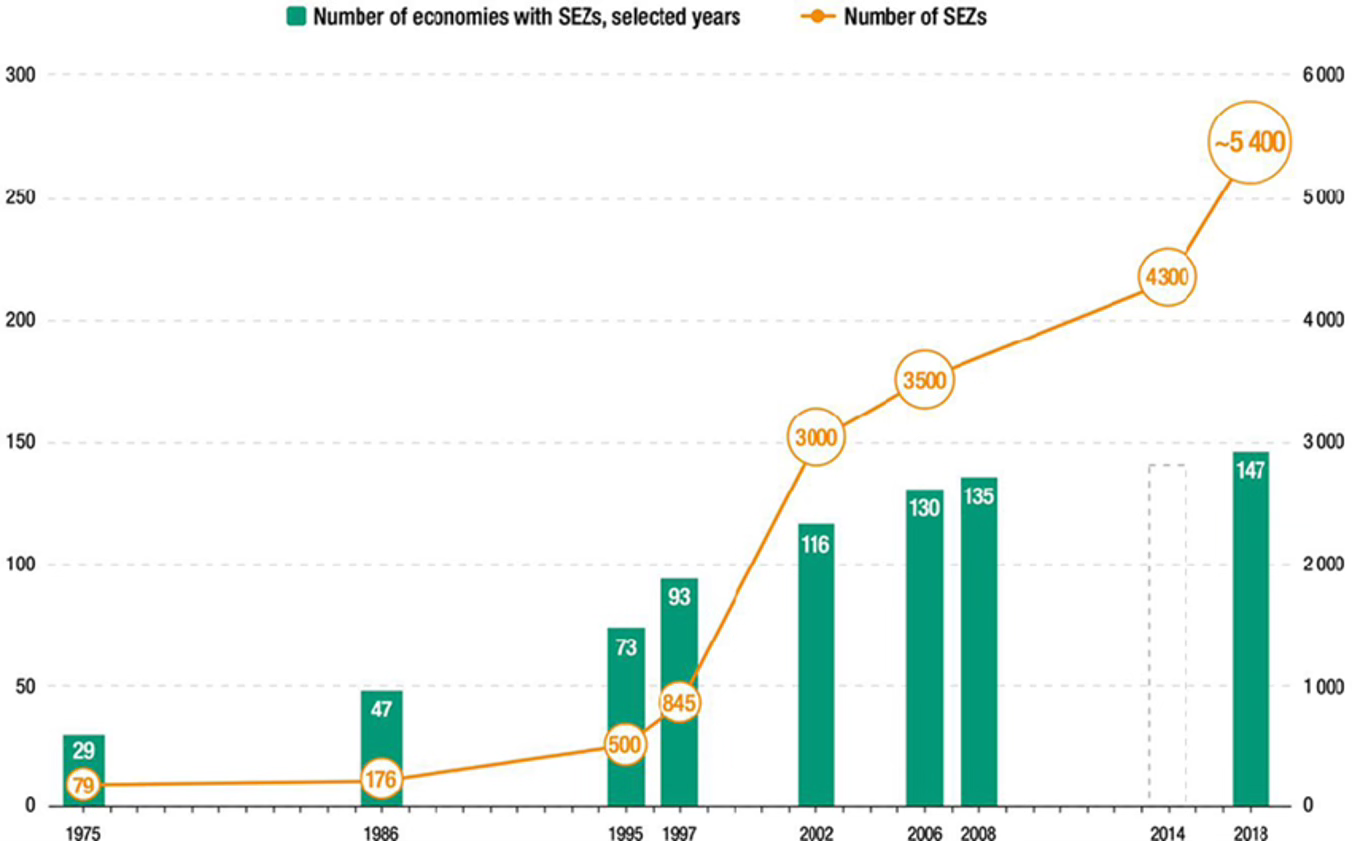

Here is a graph illustrating this trend15 :

As you can see, we've gone from :

From 79 SEZs in 29 countries in 1975

To 5,400 SEZs in 147 countries in 2018 (!)

This meteoric rise began in earnest in the 2000s, around the same time as the Internet began to disrupt nation-states.

This points to an interesting trend: while on the surface, international agreements appear to standardize many aspects of the functioning of the "master jurisdictions" that are nation-states, in reality, the sovereignty of these states is already fragmented and scattered, at least at the economic level, across thousands of zones that do not fully apply their laws, within their own territory, and with their blessing.

(In the second part, we'll see that the next stage - granting some of these areas autonomy not only economically, but also politically and socially - is already underway).

And that's one possible response to this kind of agreement: a country's façade is in line with the terms of international regulations, but there are SEZs on its territory, with different rules, which in practice mean that it is not subject to this agreement.

5. Limiting growth

Finally, an obvious way for companies to circumvent these two pillars is to ensure that they do not meet the criteria for being subject to them.

Fortunately, there are already regulations that apply to different thresholds in different countries, so let's take a look at two examples of what happens in reality.

The example of France

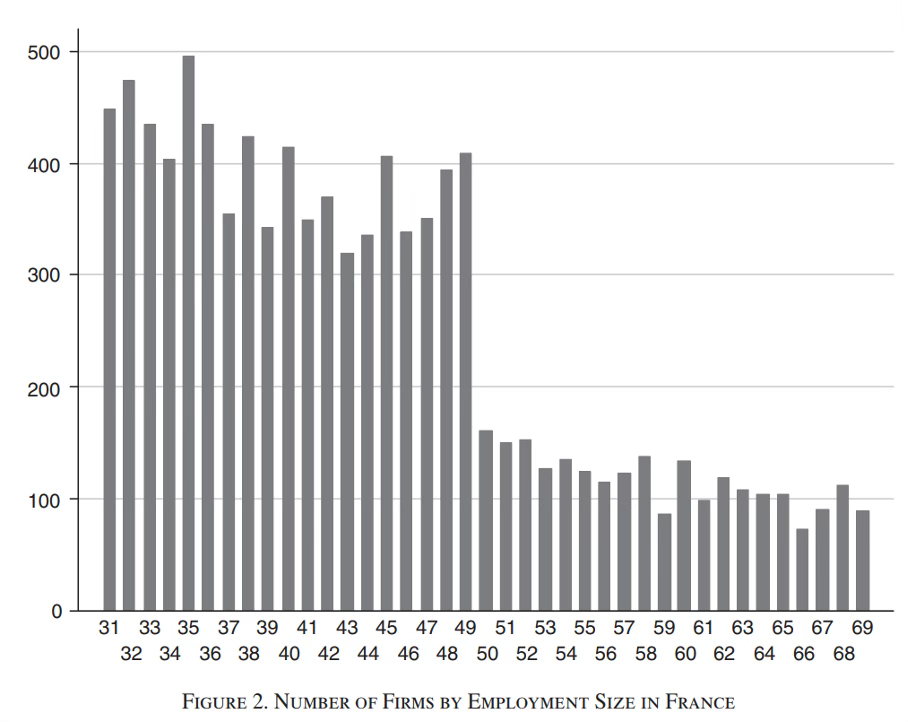

In France, numerous regulations apply to companies that reach the 50-employee threshold16:

Monthly declaration of details of all employment contracts to the authorities

Obligation to set up a works council meeting at least every two months, with a minimum budget of 0.3% of payroll

Obligation to set up a health, safety and working conditions committee (CHSC)

Appointment of a shop steward at the request of employees

Obligation to carry out a formal "professional assessment" for every worker over the age of 45

Increased obligations in the event of workplace accidents

Obligation to use a complex redundancy plan with supervision and approval

And control by the Ministry of Labour in the event of an occupational accident

It's not gradual: if you have 49 employees, these regulations don't apply; if you have 50, they do.

The result is that employees are much better protected thanks to the fact that companies are obliged to implement these regulations, aren't they?

Well...

Let's see if there are any anomalies in company size in France17 :

As you can see, there's a huge drop in the number of companies exactly above the 50-employee threshold.

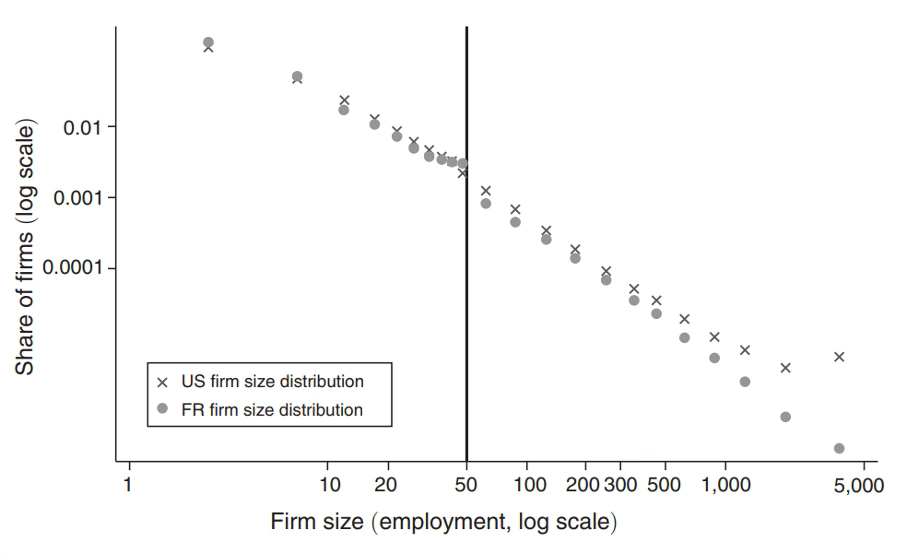

Now let's compare with another country, the United States:

We can see here that French companies are proportionally more numerous than American companies in not crossing the 50-employee threshold, and that above this threshold, French companies are proportionally much less numerous than their American counterparts (the much higher number of companies with 1,000 or more employees in the USA is probably explained by the country's greater size).

My first company, in France, was an IT services company, mainly for professionals, so I've had the opportunity to work with a lot of companies in my native region, and believe me: I've heard the managers of these companies say so often that they wouldn't want to reach 50 employees that I can only confirm the results of the studies.

We can therefore say that this regulation, designed to protect workers :

Reduces the number of companies looking to grow

Reducing the number of jobs available

And those companies that prevent themselves from growing also prevent themselves from innovating, improving, and serving more customers, which reduces the country's economy all the more.

In short, it's a fiasco: researchers estimate that this regulation alone costs France 3.4% of its GDP every year18 (i.e., for the year 2022, a cost of nearly 90 billion euros19 , and tens of billions of euros less in tax revenue), for companies, it corresponds to a 2.2% tax on profits, reducing innovation in France by around 5.4%, cutting growth by 1.9 to 2% a year, and reducing the well-being of French society by at least 2.2%20 .

The example of Great Britain

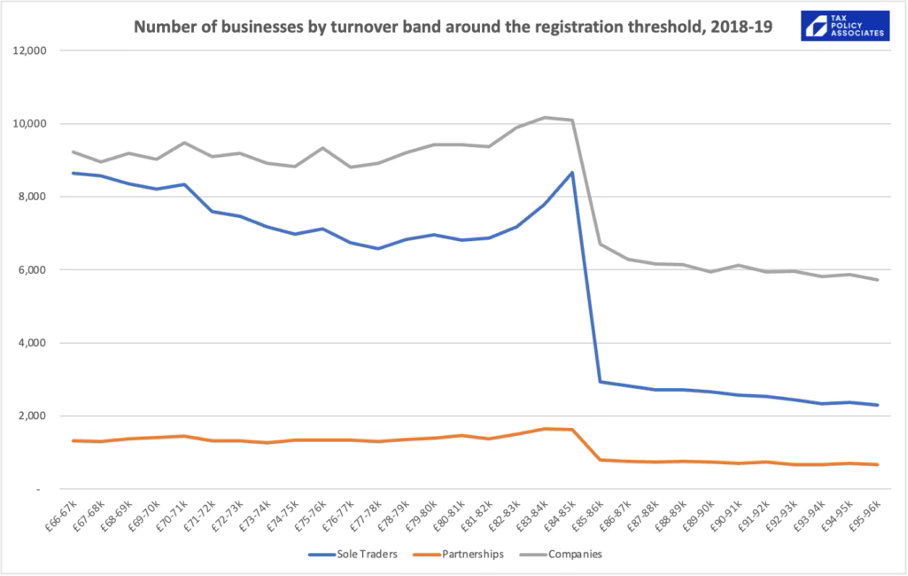

In the UK, companies with sales of less than £85,000 do not charge (or reclaim) VAT.

As soon as they hit the £85,000 mark, they have to raise all their prices by 20% (the UK VAT rate, at the time of writing), or reduce their margins by the same amount, or opt for a mixture of the two.

Result? Here's the number of companies in Great Britain in 2018 by sales21 :

As you can see, the impact of this limit on behavior is significant.

Impact on the two OECD pillars

We can therefore expect to see many more companies "blocked" at 750 million euros, and 20 billion euros, in sales.

Of course, the thresholds will probably be lowered over time. In any case, some countries will try. But it's extremely difficult for over a hundred countries to coordinate, especially over the long term, given their divergent interests, and dozens of them will be tempted to cheat or negotiate advantages.

However, inflation will take its toll: at 2%, the 750 million euros threshold will be equivalent to 521 million euros 20 years later.

At the end of the day, regulations often encourage the entities subject to them to bypass them rather than comply with them, and this is all the more true in a complex international context: I'm willing to bet that the results of this OECD reform will be disappointing compared with forecasts.

And I bet they'll add a lot of friction to the wheels of society, costing far more than they bring in.

In conclusion : even if it works, it diminishes the power of the majority of nation-states.

Firstly, because the 15% rate is already an admission of impotence: let me remind you22 that the weighted world average for corporate income tax (CIT) in 1980 was... 46.52%!

Today, countries are fighting to apply a 15% rate, whereas 40 years ago the corporate tax rate was three times higher, and there was no need for a cartel to apply it!

And the average corporate tax rate was 23.45% when the OECD agreement was signed... not 15.

By 2021, only 47 of 225 jurisdictions had corporate tax rates below 15%, and 115 had rates above 20%23 .

As a result, many countries will continue to suffer from tax competition until they reach the minimum rate of 15% - which, as we have seen, will probably not be the true floor rate.

What's more, each international agreement that is ratified further restricts what a state can do on its own soil, as the terms of the agreement that binds it limit its room for maneuver.

And since international treaties always take precedence over laws, this further diminishes the sovereignty of the State over its own territory, and therefore its legitimacy. Q.E.D.

A loss of legitimacy means less support from the population, or at least from part of it, which weakens the "Nation" part of the nation-state, and therefore the state, contributing to an increase in the number of would-be expatriates eager to take advantage of the market of the jurisdictions fighting to attract them.

So if nation-states win on the one hand with this kind of agreement, they will also lose on the other. It's an insoluble dilemma.

Coming soon

In the next article, we'll look at how governments can use their laws and regulations to combat the disruptions that threaten them.

Stay tuned ! In the meantime, feel free to follow Disruptive Horizons on Twitter, and join the tribe of Intelligent Rebels by subscribing to the newsletter :

And here are the first 4 articles of this series :

"Entente confirmée : sort des victimes et de la concurrence non réglé", Que Choisir, 2006

20% profit, half of which (above the 10% threshold) is considered surplus profit. A quarter of these surpluses will be divided, half between the five European countries mentioned, and half to the benefit of the United States.

"Possible Effects Of Adopting The OECD's Pillar Two, Both Worldwide And In The United States," Joint Committee on Taxation, 2023

Siqalane Taho, "Report lays bare BEPS' failure to reverse profit shifting", International Tax Review, 2022

"Background And Analysis Of The Taxation Of Income Earned By Multinational Enterprises", staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation, 2023

Jesse Drucker, "Man Making Ireland Tax Avoidance Hub Proves Local Hero," Bloomberg, 2013

"Corporate tax calculations", The Irish Times, 2014

David Kamin, "The Ambition and Limits of the Global Minimum Tax", Tax Notes, 2022

Martin A. Sullivan, "Does Pillar 2 Provide a Windfall to Tax Havens?", Tax Notes, 2023

Or, in the case of federations, the state, province, emirate, etc..,

From Julien Chaisse and Georgios Dimitropoulos, " Special Economic Zones in International Economic Law: Towards Unilateral Economic Law "Journal of International Economic Law, 2021

Philippe Aghion, Antonin Bergeaud & John Van Reenen, "The Impact of Regulation on Innovation", National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021

Diagram taken from Luis Garicano, Claire Lelarge and John Van Reenen, "Firm Size Distortions and the Productivity Distribution: Evidence from France," American Economic Review, 2016.

France's 2022 GDP of 2,642 billion euros

"The Impact of Regulation on Innovation", op. cit.

"Is VAT stopping 26,000 businesses from growing? More on the VAT growth brake", Tax Policy Associates, 2023

As we saw in this article.

"Corporate Tax Rates around the World, 2021", Tax Foundation

You make a good point that even if the cartel works, it won't stop the ongoing trend of decreasing corporate tax rates so that in this worst case scenario, as a result of competition we'll have a global 15% corporate tax rate all around the world, which is way lower than what we have today (Brazil 34%, France, China, India & UK 25%, Japan 23%, US 21% and Germany 16%). Of course, that's the worst case scenario and as you said the project can fail, the cartel can explode, and there are loopholes.

"Of course, the thresholds will probably be lowered over time.": they don't even need to lower them, inflation will do the job! In 20 years, €750m might be the equivalent of €400m today.

Also: could companies just split before reaching the threshold? Example: company A has annual sales of €700m. They split in A1 (that only sells in a specific region, or that only sells some of the products) and A2, each of them with about €300m of annual sales. A1 and A2 can share the same name, they can be partners, etc. as long as they're independent. A could also just sell some of its assets to avoid reaching the threshold. It's extremely inefficient for society as a whole (like the French 50-employee threshold) but it would make Pillar 2 useless.