Is the EU killing itself with regulations?

A few interesting studies and examples

"I wanted America to remain the bastion of free enterprise, and to do everything in my power to prevent it from following the European path of bureaucracy and stagnation. Because that was the Europe I'd lived in."

Arnold Schwarzenegger, recounting his memoirs as Governor of California

in his biography Total Recall

Note : This article is the 3rd in a series on over-legislating a a path that more and more nation-states are taking in an attempt to emasculate the disruptions that threaten them.

Here is the first two articles in the series :

Some countries will try to react to the profound disruptions they will experience from the Internet and globalization by trying hard to regulate them.

A striking example of this is unfortunately the European Union, which has the unfortunate reputation of being the world champion of regulations and bureaucratic rules of all kinds.

Arnold Schwarzenegger's statement makes this clear, as does a simple stroll through X/Twitter in English.

But is it true?

The impact of regulations on the economy, and Eurosclerosis

First of all, the impact of too many regulations on entrepreneurship and the economy has1 been 2 amply3 demonstrated4 : the more regulations there are, the more they have a negative effect on the economy.

Then, one of the founding studies of this field of research looked precisely at why the European Community (the forerunner of the European Union) had lower growth and innovation, and higher unemployment, than the USA and Japan in the 1970s through to the mid-1980s (when the study was published). The study concluded that this was due to "structural rigidities" and excessive regulation, and gave the phenomenon the name..."Eurosclerosis"5!

Since then, most researchers believe that Eurosclerosis as defined at the time no longer applies to the European Union6 ... which is not to say that it is a paragon of innovation and bureaucratic lightness either, as we shall see. Some researchers now speak of "European Osteoporosis7 ".

In any case, the term "Eurosclerosis", used today to describe any country whose growth and employment are held back by too many regulations, is a reminder that this is clearly a European problem at the core.

More regulations in the EU than in the USA?

It also seems clear that regulations in the fields of new technologies and corporate finance are more onerous in the European Union than in the United States, with the GDRP (which we'll look at in depth in a later article), the Digital Services Act, the Digital Markets Act, the Data Governance Act, the Data Act and the Artificial Intelligence Act, new regulations implemented while “both Democratic and Republican administrations have generally considered existing regulations sufficient8”.

This is probably due to the fact that the EU is hopelessly lagging behind the USA in the field of digital technologies, an essential industry that is taking an increasingly important part in society, to the extent that very official9 bodies10 are now talking about the "digital colonization" of Europe.

For example, if we look at the top 20 companies with the highest market capitalization in the world in March 2024, we see that

Nine companies are in the technology sector,

and these nine are all American, except for one based in Taiwan, TSMC, which manufactures processors and microconductors.

(In fact, 16 of the world's biggest companies are American! As for the rest, there's one Saudi company (Saudi Aramcom, oil), one Taiwanese, as we've seen, and just two European ones, Novo Nordisk in Denmark (pharmaceuticals11 ), and LVHM in France, in the luxury goods sector, i.e. two European companies out of twenty)

Similarly, in early 2021, the 30 largest technology companies in the USA had a market capitalization equivalent to the GDP of the 4 largest EU economies (Germany, France, Italy and Spain) + Great Britain12.

And the European Union is overreacting, trying to regulate an industry over which it has no control, in the hope that this will be enough to compensate for its lack of innovation in the field.

Unfortunately, as we shall see:

Europe tends to over-regulate, implementing regulations too quickly.

These regulations are often cumbersome, complex and applied in very disparate ways, depending on the country and the company.

They often come at a high cost to society.

And are sometimes absolutely ridiculous (we'll see several examples below).

As over-regulation is an obvious defense mechanism against technological disruptions, and one that has been used on numerous occasions throughout history (as we saw with principles 4, 9 and 11 in series 1 and 2), I'm going to focus on the case of the European Union, as it is emblematic of what other countries could try.

First, let's look at an example from the finance sector, which nevertheless has repercussions for the entire technology subsidiary, before examining direct examples from the latter.

Venture capital

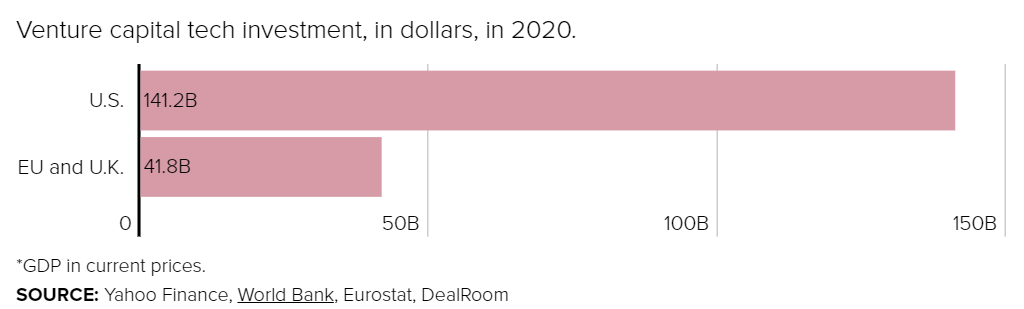

To set up a venture capital company - a very important step for business angels to finance startups, and one that has made California and the United States rich - it takes one day in the state of Delaware, and two months in most European countries, at a cost two to three times higher than in the United States.

What's more, if this company needs to raise funds from investors residing in different EU countries, it must obtain a European "passport", a process that takes additional months and is particularly time-consuming, whereas this requirement does not exist in the United States13 .

This is a major obstacle in an area that is strategic because it forms the basis of a dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem, as can be seen in the amount of funding available between the two economies:

A Windows that nobody wants

It's 2004, and the headlines are full of news: the European Union has imposed the heaviest fine in its history14 (at the time), 497 million euros, on Microsoft, accusing it of abusing its virtual monopoly in PC operating systems to impose software which, according to the Commission, should be freely chosen by private market players.

Had Microsoft included its Office suite in Windows, forever closing the doors to potential competitors? Had the company imposed its browser to the point of refusing to install any competing web browser?

Quite the contrary. What led the Commission to impose this fine of almost half a billion euros was that Windows came with software designed to play audio and video files.

Yes, you read that right: in 2004, the Commission ruled that it was not normal for an operating system installed on the computers of hundreds of millions of Europeans to be able to play multimedia files as soon as the PC was switched on.

And not content with imposing this fine, it demanded that Microsoft release a version of Windows without this reader.

Microsoft complied, calling this edition "Windows XP Edition N", but selling it at the same price as the one including the player.

The result? A commercial failure. And that's normal: who would want an incomplete version of a product for the same price as the full product?

Major computer manufacturers also shunned it, and consumers showed very little interest15, with only around 1,500 units shipped to computer integrators, and no direct consumer sales reported.

Yet even today, Microsoft still offers an "N" version of its operating system, which nobody buys, as it has done continuously since 2004, just to comply with this European regulation.

It's a textbook case of how ridiculous and pointless regulation can be, and how it can be a source of jokes at the expense of its instigators.

Well, except for the entity that has to endure this regulation, and sometimes the hefty fine that goes with it, who finds it a lot less fun, of course.

It's worth noting that I understand what the Commission was trying to do: personally, I don't like the Windows media player, and one of the first things I do when I buy a new computer is install VLC, a free, open source program that I find to be of much higher quality.

But this is precisely the point: Microsoft has never prevented anyone from installing the media player of their choice.

So here we have a typical example of a regulation and a decision that had no concrete effect on consumer behavior, and against which there were solid arguments (it seems normal, when you buy a computer or a smartphone, to be able to play videos or audio files immediately), but which nevertheless came down with the full force of the law on a company.

And that's not counting the injustice of imposing such a fine on just one company: if the European administration still thought it was in the right, why not have attacked Google for including a video player in Android smartphones, and Apple for doing the same in iPhones?

And if she didn't do it because she realized her mistake, why didn't she admit it and reimburse Microsoft? Or was it just an attempt at extortion?

Why stop there? Browsers

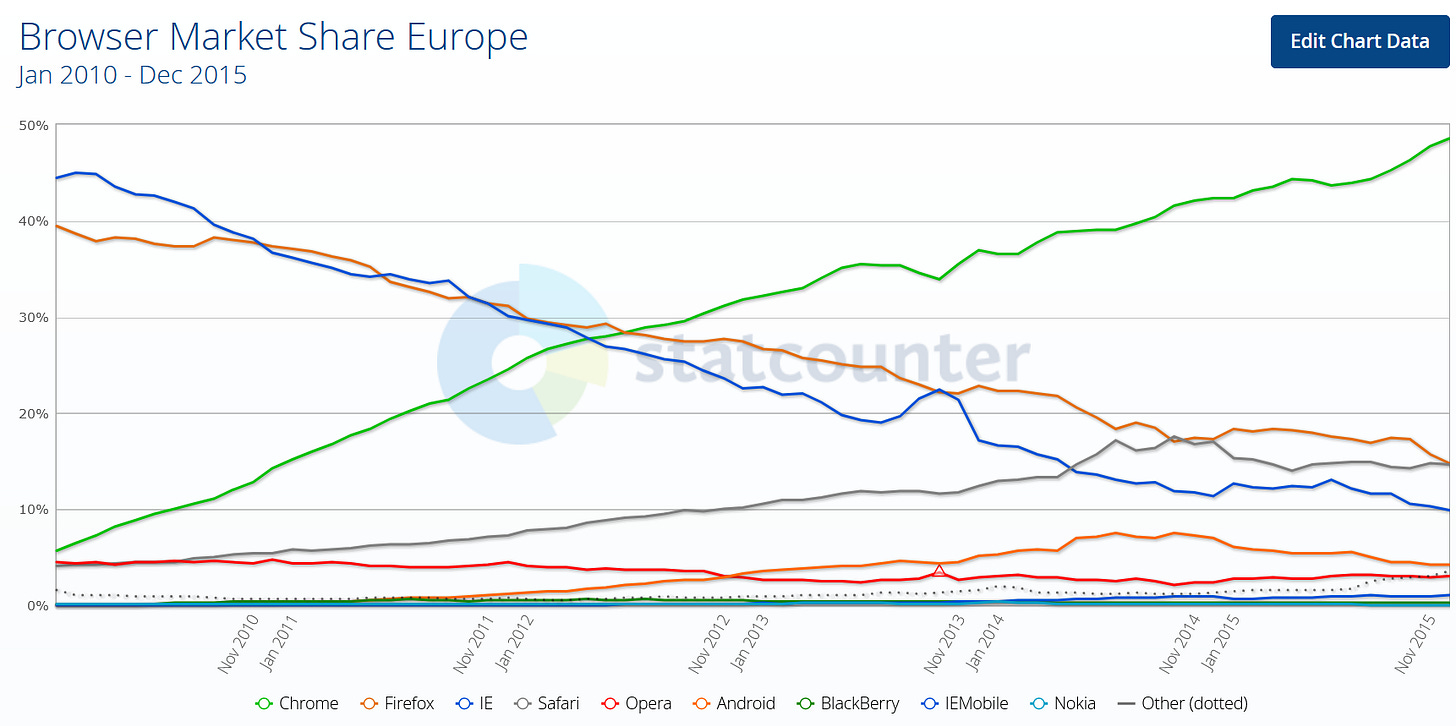

In 2010, the Commission repeated its decision, obliging Microsoft to display a screen allowing users to choose their web browser from a pre-selected list16 until December 2014, so that the company could not take advantage of its virtual monopoly with Windows to impose its browser.

The five browsers featured were the most popular at the time the choice was made: Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, Opera and Safari17 .

What impact has this regulation had? Let's see by comparing the market shares in Europe18 of the three most popular browsers, in January 2010 (just before the introduction of the choice screen in Windows) and in January 2015 (just after the regulation expired and the choice screen disappeared):

Internet Explorer

January 2010: 44%

January 2015: 12%

Ah ah, you say! This regulation worked!

Not so fast: let's take a look at the figures for other browsers.

Firefox

January 2010: 39%

January 2015: 18%

Chrome

January 2010: 5%

January 2015: 42%

Opera

January 2010: 4%

January 2015: 2%

As you can see, despite being promoted in exactly the same way, Firefox and Opera saw their market shares decline, while Chrome's exploded!

So it wasn't because people had a choice screen in Windows that they started opting for other browsers, but simply because it was becoming common knowledge that Chrome was better than all the others19 .

If this had been thanks to the choice screen, the other browsers highlighted would have gained market share in equal proportion to Internet Explorer's losses.

In addition :

Internet Explorer was already losing ground before this regulation, dropping from 50% market share in Europe in January 2009 to 44% a year later.

Worldwide trends were exactly the same, providing irrefutable proof that the choice screen had changed nothing, since it had only been introduced in the European Union

Finally, this case shows that not only has the Commission implemented a cumbersome and useless regulation, but also that the very problem it thought it was solving didn't exist: it thought it was helping the market to function, when it was already functioning very well, since people were free to change browser if they wished, and did so, with or without the choice screen.

This is the problem with many regulations put in place by bureaucrats, particularly European bureaucrats: they try to solve problems that don't exist.

And when these bureaucrats tackle "problems" in the field of new technologies, their incompetence is compounded by the fact that they often have a limited understanding of the technologies they are trying to regulate, and an even more limited understanding of future trends in these technologies.

Coming soon : the infamous GDPR

In the next article, we’ll take a look at the most infamous of European regulations: the GDPR. We'll examine whether its sad reputation is truly deserved, and what impact it's having on the European economy and innovation.

Stay tuned ! In the meantime, feel free to follow Disruptive Horizons on Twitter, and join the tribe of Intelligent Rebels by subscribing to the newsletter :

And here are the first 2 articles of this series :

Leora Klapper, "Entry Regulation As A Barrier To Entrepreneurship", Cambridge, 2004

Giuseppe Nicoletti, "Regulation, Productivity and Growth - OECD Evidence", Oxford, 2003

Bernard Hoekman, "Trade policy, trade costs, and developing country trade", World Bank, 2008

"Hiring and firing workers", Doing Business in 2005, World Bank

Herbert Giersch, "Eurosclerosis", Kiel Institute for World Economics, 1985. This was a visionary research article, predicting that new computer technologies would promote economic decentralization and thus deregulation, while warning of the Orwellian dangers of a centralized digital economy.

Tito Boeri, "Beyond Eurosclerosis", Economic Policy, 2009

Murat Necip Arman, "Eurosteoporosis: A Novel Proposal for a Discussion on the Acting Level of the European Union in International Politics", Portuguese Journal of Political Science and International Relations, 2012

"The Eu - Us Tech Relationship In A “Changing Global Economic Order”, Eit Digital Makers & Shapers, 2023

Catherine Morin-Desailly, "L'Union européenne, colonie du monde numérique?", information report by the French Senate, 2013

Julien Nocetti, "L’Europe reste-t-elle une « colonie numérique » des États-Unis ?”, Institut national du service public, 2021

Thanks above all to Ozempic, a miracle drug against obesity.

« 5 charts that explain the digital transatlantic relationship”, Mark Scott, Politico, 2021

"The Best Venture Capital Domiciles", Decile Group, VC Lab

"Microsoft hit by record EU fine", CNN, 2004

Graeme Wearden, "Windows XP-lite 'not value for money'", Silicon magazine, 2005

"The Browser Choice Screen for Europe: What to Expect, When to Expect It", Microsoft, 2010

Safari was then replaced by Maxthon. If you've never heard of this browser, that's normal, but it overtook Safari in popularity when Apple discontinued Safari for Windows.

Source: Statcounter Global Stats

Hiten Shah, "From 0 to 70% Market Share: How Google Chrome Ate the Internet", Nira.