The Worst Moment: The Growing Difficulty Of Nation-States To Raise Taxes

Taxing times just when the Internet and globalization are disrupting them.

In the previous series of articles, corresponding to Chapter 1 of my forthcoming book, we saw all the factors that are making the Internet and globalization disrupt nation-states.

With this article, we start a 4-part series in which I'll try to demonstrate that this disruption is coming at the worst possible time for them.

Let's start where it hurts: the ability to raise taxes.

Nation-states are in a difficult situation today, as the conditions that made them powerful and wealthy in the 19th and 20th centuries are crumbling, even as governments continue to make the classic promises of the 20th century without their 21st century means being able to pay for them, and their populations really realizing it, as we shall see.

Nation-states find it increasingly difficult to tax individuals and companies

Let's compare, for example, the percentage of taxes in the highest income tax bracket, between 1950 (year of the apogee of the centralized, industrial nation-state) and 20171 for 4 G7 countries:

And here's the same information in table form:

As you can see, these 4 major countries tax their wealthiest populations (those in the top income tax bracket) much less in 2017 than in 1950.

Why is that? Because the airplane, the telephone, and now the Internet have made these people much more mobile, and rates that are too high make them flee to more welcoming countries.

And that those who remain are much less motivated to work and bring value to the company.

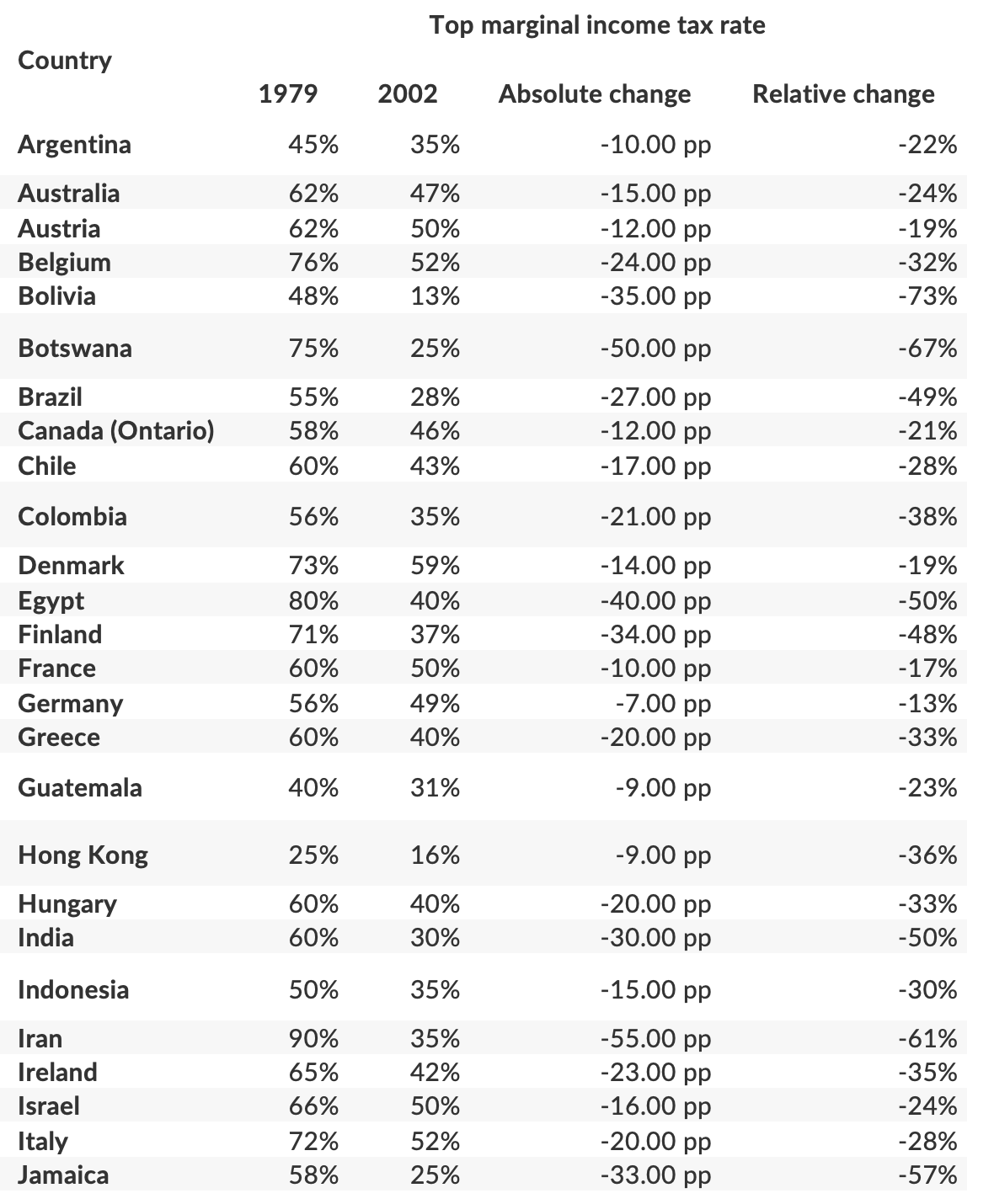

And if you think this data has been carefully chosen to support that view, here's the same data for 49 countries between 1979 and 20022 :

You can look: of all these countries, not a single one has not reduced its top marginal income tax rate.

Not one.

And yet, in 2002, the Internet had barely begun to disrupt society as a whole. But the trend had already begun in this highest tax bracket, as the most affluent population was the most mobile.

Today, the Internet makes this mobility accessible to any member of the middle class who works remotely. How do you think this will affect nation-states' ability to raise taxes?

Corporate taxes

And it's the same with corporate taxes: between 1980 and 2021, the average corporate tax rate worldwide fell from 40.11% to 23.54%, a 41% drop in 41 years3 .

If we look at the weighted average (an average that takes into account the economic weight of each country rather than just the "dumb" average), it's even worse: from 46.52% in 1980 to 25.44% in 2021, a reduction of 45% over the 41 years studied4 .

Most analysts who talk to you about this global phenomenon affecting both companies and individuals will focus on this or that president or government who decided on this or that cut, detailing the reasons for it, or explaining that it's the fault of evil multinationals and greedy individuals who artificially lower their taxes by moving offshore.

But these analysts, by looking too closely at the details, miss the big picture: if these companies and individuals can do this today, it's because we're gradually moving from a society made up of industrial, centralized and immobile companies, to one made up of digital, agile companies, some of which no longer even need a fixed physical location.

What's more, electronic money exchanges make it very easy for capital to cross borders, allowing it to be placed in welcoming jurisdictions that will tax it little or not at all.

Take a look at this diagram, which shows the percentage of foreign-generated revenues of US multinationals that are "issued" from tax havens:

The orange curve represents the activity actually generated from the jurisdictions in question, while blue represents the percentage of profits considered to be artificially displaced5.

Nation-states have been trying to combat these "paper" transfers, notably since the 2010s6 , with little result so far7 , and if they succeed, they will probably just encourage multinationals to relocate many jobs to tax havens, in order to have a real presence in these countries, and ensure that there are no more "paper" transfers but the generation of a real economy.

This is because we are moving from a society made up of immobile individuals and companies who could only with great difficulty leave their country and even their region, to a society of mobile individuals who are less and less mono-country, and some of whom no longer even need a fixed physical location.

Millions of people and businesses are gradually freeing themselves from the tyranny of location.

This trend is inevitable, and has been undermining the foundations of nation-states for decades. And, as we shall see in later articles (and in the book), attempts at international cooperation to halt this phenomenon will not have a major impact on it.

A curious phenomenon

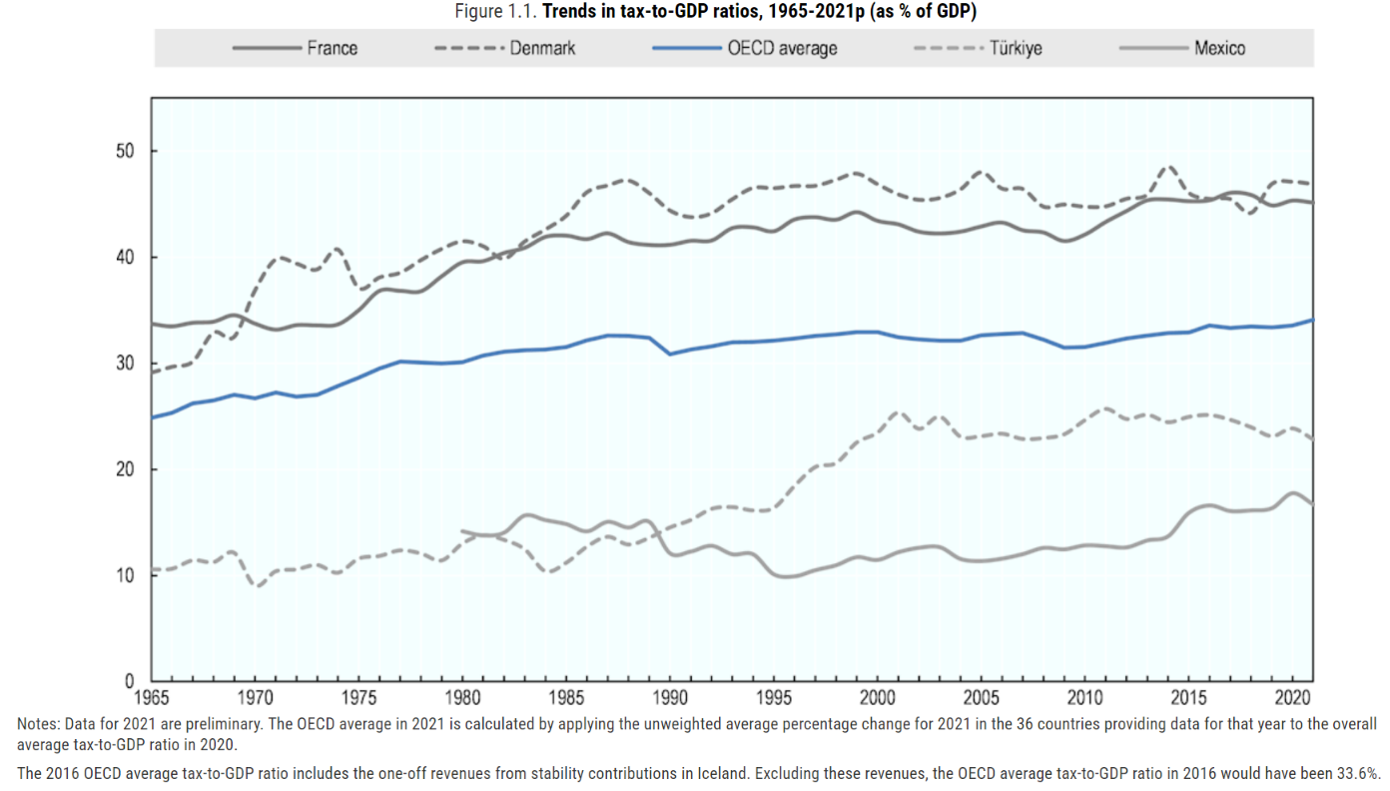

However, an interesting phenomenon has occurred: while corporate and income tax rates have fallen steadily, the weight of total compulsory levies in OECD countries has increased in relation to the countries' GDP, rising from 24.9% in 1965 to 34.1% in 20218 :

How is this possible?

A better fight against tax fraud?

This would seem to be unsubstantiated, as the fight against tax fraud does not earn states much money in relation to their total tax revenues.

For example, here are the figures for France9 :

So we can see that in the case of France, the average tax bill is just over 3% higher.

It should be noted that these revenues (actually received) are different from the amounts claimed by the tax authorities, which are generally twice as high! Yes, on average, the French tax authorities recover just under half the sums they claim.

For the United States, the IRS indicated in 2022 that it had claimed the sum of $30.2 billion10 , for US tax revenues of $5,008 billion in the same year11 .

The IRS doesn't disclose how much it actually collects, so let's make two assumptions: if it collects around 50% of the sums it claims, like the French tax authorities, the additional revenue generated by the IRS in 2022 is therefore 0.3% of US revenue.

If it manages to recover all of this (let's be optimistic), it represents 0.6% of US tax revenues.

Many countries are not as transparent as France about the sums they recover following tax disputes, but make more vague estimates, such as Great Britain, which estimates a tax gap of 4.8% between taxes that should have been recovered and those actually received12 , which is still not very high.

In short, a straw: as we can see, even if the fight against the effectiveness of tax fraud has doubled since 1980, this is not the reason for the increase in taxes collected13 .

What's more, several tax departments are complaining about their growing difficulties in collecting taxes, such as the US IRS, which in 2022 complained that the tax gap (the gap between taxes collected and those that should have been collected if everyone honestly declared their income) had been calculated at $496 billion a year for the 2014-2016 period, up $58 billion a year on the 2011-2013 period, and estimated at $540 billion a year for the 2017-2019 period, up by $44 billion a year14 .

Clearly, this is not the reason why the amount of taxes levied has increased, while the tax rate has been halved.

The answer

This diagram15 , gives us the answer, showing the evolution of effective (not theoretical) tax rates on labor, capital and business profits worldwide:

Clearly, the tax rate on labor has risen (sharply) - including social security contributions - while those on capital and business profits have fallen.

This shows one of the effects of the disruption of nation-states by the Internet and globalization: as states find it increasingly difficult to tax mobile companies and individuals, they increasingly tax the generally immobile, single-country middle class, which has not yet integrated the new paradigm of mobility into its way of operating.

And social security contributions must also rise to offset the growing costs of an ageing population, as we shall soon see in the next article.

As well as VAT

VAT has been gradually introduced in various countries, and its share of global public finances has continued to soar, accounting for just 2.21% of OECD tax revenues in 1965, and 20.18% in 2020.

The average rate rose from 15.6% in 1975 to 19.2% in 2022:

The appearance and subsequent increase in VAT also explains the rise in compulsory deductions, affecting above all those who stay behind.

Increase in corporate income tax revenue as a % of GDP

Similarly, this diagram shows that the share of corporate income tax in the economy has risen from 2.4% in 1981 to 3.5% in 2021 in 22 OECD countries (and corporate income tax revenues as a share of total revenues have also tended to increase since the 1980s):

How is this possible?

Beyond the diagram presented above, various 16 studies17 show18 that the drop in the average corporate tax rate is 1) real (it's not just the "official" rate that has fallen, but the effective rate at which companies are taxed) and 2) has a real impact on the taxes that governments can raise (one study estimates a 15% loss of profits for EU countries, and a 10% loss for the USA due to tax competition between countries ).19

So there are several possible reasons for this apparent contradiction:

The Laffer curve

It's an economic theory which says, roughly speaking, that the more a government taxes its population and businesses, the less they'll want to contribute to the economy, both because they'll be less inclined to work (what's the point if the state takes a large part of what they earn?) and because they'll have less money to invest and save (which reduces the amount of money they can invest, and that the banks can invest).

According to this explanation, lowering taxes has actually benefited countries, enabling them to stimulate their economies20 .

It also seems likely that, when companies are taxed less, they generate more profits, which they reinvest in part, thereby increasing profits over time and generating more tax revenue for the State.

Greater profitability for companies

The average profitability of companies is increasing over time, thanks in particular to technological factors such as plant robotization, computerization and digitization.

For example, a traditional publisher has to plan a completely different budget for a book depending on whether it sells 1, 1,000, 10,000 or 100,000 copies: printing, storage, distribution and returns management costs are completely different.

An e-book publisher, whether it sells 1, 1,000, 10,000 or 100,000 copies, has an identical storage, distribution and returns management budget: zero, or close to it.

Its gross margin is absolutely enormous compared to a traditional publisher, and this is true for many digital companies, including those that have replaced more traditional businesses: Netflix has a bigger gross margin than the VHS and DVD movie rental company Blockbuster Video, which at its peak in 2004 had to pay the salaries of 84,300 people and rent or buy 9,094 stores, for sales of $6.1 billion21 (equivalent to $9.4 billion in 2022 dollars) - whereas Netflix in 2022 had to pay the salaries of 12,800 people for sales of $31.6 billion22 .

This graph already gives a good idea of what happens when a company digitizes its services, or when a natively digital company replaces a traditional, pre-Internet company...

But this graph is even more telling: the value generated per employee is exploding.

If we look at gross margin, which allows us to compare profitability directly, we're at $3.6 billion for Blockbuster in 2004 (equivalent to $5.6 billion in 2022) and $12.44 billion for Netflix in 2022.

In the end

The fall in corporate and income tax rates is therefore a direct result of tax competition between nation-states, exacerbated by globalization and the Internet, and it's fair to say that tax rates are increasingly dictated by external rather than internal conditions.

The fact that corporate tax revenues have risen as a proportion of GDP reflects the increasingly important role played by business and the private sector in the economy, which also shows that the private sector is becoming more powerful than the public sector.

Finally, the increase in the weight of compulsory levies, even as effective income and corporate tax rates rise, is due to the fact that sales taxes, such as VAT, and social security contributions are soaring, because these are "invisible" taxes that most people don't see, and which disproportionately affect the single-country, immobile middle class, who generally don't even realize what's happening to them.

And most nation-states have to increase social security contributions, which brings me to my next article, on the demographic time bomb that's just around the corner.

And before you go read this article:

Next articles of this series :

The most recent data available in this source: "World Inequality Report 2018", Alvaredo, F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (Eds.)...

Alan Reynolds. "Marginal Tax Rates." The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. 2008. Library of Economics and Liberty.

"Corporate Tax Rates around the World, 2021", Sean Bray, Tax Foundation

The big drop in the blue curve in 2017 is due to the change in the US federal corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%: given their weight in the global economy, this is immediately apparent in the weighted average curve!

"Global Tax Evasion Report 2024", EU Tax Observatory, 2023

With, in particular, BEPS, "Base Erosion And Profit Shifting", and the OECD's global agreement on the minimum tax for multinationals (pillars 1 & 2).

"Global Tax Evasion Report 2024, quoted above

"Revenue Statistics 2022: The Impact of COVID-19 on OECD Tax Revenues - Tax revenue trends 1965-2021".

"Les recettes fiscales de l'État", Cour des Comptes annual report for each year, and "Impôts: les contrôles fiscaux ont fait entrer 11 milliards dans les caisses de l'Etat en 2021", Isabelle Couet, les Echos, for revenue from tax audits.

IRS Data Book, 2022, "Compliance Presence" section

"How much revenue has the U.S. government collected this year?", U.S. Treasury website, 2023

"HMRC Annual Report and Accounts, 2022 to 2023". In short, this estimate isn't worth much, and the UK taxman doesn't disclose 1) the sums claimed each year from taxpayers, and 2) the sums actually recovered.

Of course, an effective fight against fraud would also have a deterrent effect that would reduce the volume of fraud, and some research ("Why Can Modern Governments Tax So Much? An Agency Model of Firms as Fiscal Intermediaries", Kleven, Kreiner, & Saez, 2016, London School of Economics ) shows that the larger a company is, the less likely it is to commit fraud - because it needs to keep accurate internal accounts to manage its operations, and the risk that an employee might reveal information leading the administration to discover fraud increases with the number of employees. But company size tends to decrease with new technologies, not increase (see the example in this article), and the dissuasive effect is difficult to measure, and may just as well contribute to more people moving abroad to greener pastures, fanning the flames of tax competition.

From "Globalization And Factor Income Taxation", Pierre Bachas, Matthew Fisher-Post, Anders Jensen, Gabriel Zucman, 2023

"The Missing Profits Of Nations", Thomas R. Tørsløv, National Bureau Of Economic Research, Cambridge, 2020

"Effective tax rates of multinational corporations: Country-level estimates", Javier Garcia-Bernardo, Petr Jansky', Thomas Tørsløv, Department of Methodology & Statistics, Utrecht University, 2023

"Globalization And Factor Income Taxation", Pierre Bachas, Matthew Fisher-Post, Anders Jensen, Gabriel Zucman, 2023

"The Missing Profits Of Nations", quoted above (See footnote 16)

"The OECD Plan To Raise Taxes Is Based on Faulty Data", Adam N. Michel, Cato Institute, 2023

Great article, thanks for taking the time to dig the sources and analyze them!

I'm sure governments are aware of the situation... Hence the "global minimum corporate tax rate" proposal... ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_minimum_corporate_tax_rate )

Here's an update from 2 days ago: "As of 1 December 2023, 33 countries have either introduced draft legislation or adopted final legislation transposing Pillar Two’s model rules into their national laws. An additional 17 jurisdictions intend to implement Pillar Two, although they have not proposed legislation to do so." https://taxfoundation.org/blog/global-tax-agreement/

And they are now calls for a "global billionaire tax" as well: https://www.icij.org/investigations/paradise-papers/a-global-billionaire-tax-could-generate-250-billion-annually-researchers-say

Great article!

I definitely feel the Laffer curve warming my butt whenever I decide to do some over hours. You get more responsibilities, more nominal pay but the ROI is always against you. Try to get that promotion to see what happens!

Then people come up with all sorts of crazy terms for that: Quiet Quitting. Or that Chinese one, Laying Flat. It's just not worth it to be a wagy: you work, get taxed to your bones, and have the privilege of working harder to be taxed even harder.

That's when entrepreneurship also becomes much more attractive: you save on taxes, have no upper limit to how much you can earn, save yourself from the office politics.

The first point I think is not necessarily complete unless you expose also what were the different income levels that got you to each one. Additionally, one pernicious taxation that is not there is inflation. But that's for another day.

The Tyranny of place is becoming no more (The Sovereign Individual's book mentions this concept of mobility, take a look https://amzn.to/3tdAjUx)

Looking forward to your book! The Way of the Intelligence Rebel is already on my shelf to give my kids when they come of age.