Same People. Same Culture. 3,000% Difference in Wealth. What Really Happened?

What Happens When You A/B Test an Entire Country?

Note : This article is the 1st in a series on how the internet and globalization are disrupting nation-states—and what new governance models may emerge. Here are the first articles in this series:

Throughout this Substack, we have seen how nation states are being disrupted by the internet and globalization, and how their attempts to curb this disruption are causing them to lose legitimacy and effectiveness, while imposing enormous costs on society.

And we have seen that this is happening at the worst possible moment in their history.

Since the beginning of this second part, I have offered you individual solutions to help you succeed. But we are social animals, and we also need effective social models to live together in the best possible way.

The printing press enabled the rise of modern nation-states—built on royal absolutism and powered by gunpowder : what new forms of society will emerge from the Internet and cryptography, based on the unprecedented mobility made possible by modern means of transportation?

Let’s take a look at some of the possibilities.

Scientifically experimenting with models of governance

In marketing, a simple method to find out whether one email subject line or sales page works better than another is to do an A/B test.

What does this test involve? It’s simple: showing two variations of the same page, advertisement, email, etc. to a given audience and measuring which version performs better.

It’s a simple, scientifically established methodology for identifying which elements perform best1 .

Now, imagine if we could do this with political and economic systems—in short, systems of governance: we present a percentage of the population of a given country with governance model A and the remaining percentage with governance model B, then, a few decades later, we come back to measure which governance model has brought the most prosperity.

That would be great, wouldn’t it?

Well, the good news is that tests of this kind have already taken place in history... although generally not intentionally.

Let’s look at some historical examples of these governance experiments

I’m focusing on GDP per capita, although other metrics are possible. But generally, the higher a country’s GDP per capita, the richer it is, and the higher the quality of its infrastructure, education, healthcare, etc.

Conversely, the lower a country’s GDP per capita, the shorter its life expectancy, the more difficult its jobs, and the more limited its access to basic services such as running water and electricity throughout the day, as well as entertainment, etc.

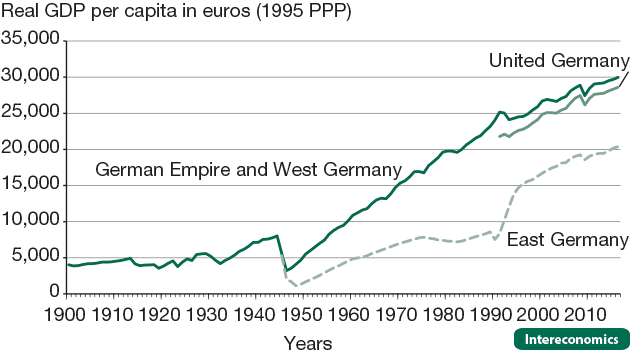

Germany

Germany was divided between West Germany (occupied and later liberated by the Americans) and East Germany (under Soviet rule) between 1945 and 1989.

Per capita GDP of West Germany in 1950: $4,2812

East Germany’s GDP per capita in 1950: $2,102

Per capita GDP of West Germany in 1989: $18,016, an increase of 321%

East Germany’s GDP per capita in 1989: $8,422, an increase of 301%3

It is also interesting to examine what happened after reunification4 :

East Germany’s GDP per capita jumped in the eight years after reunification, before returning to a similar growth rate as before, albeit at a higher level.

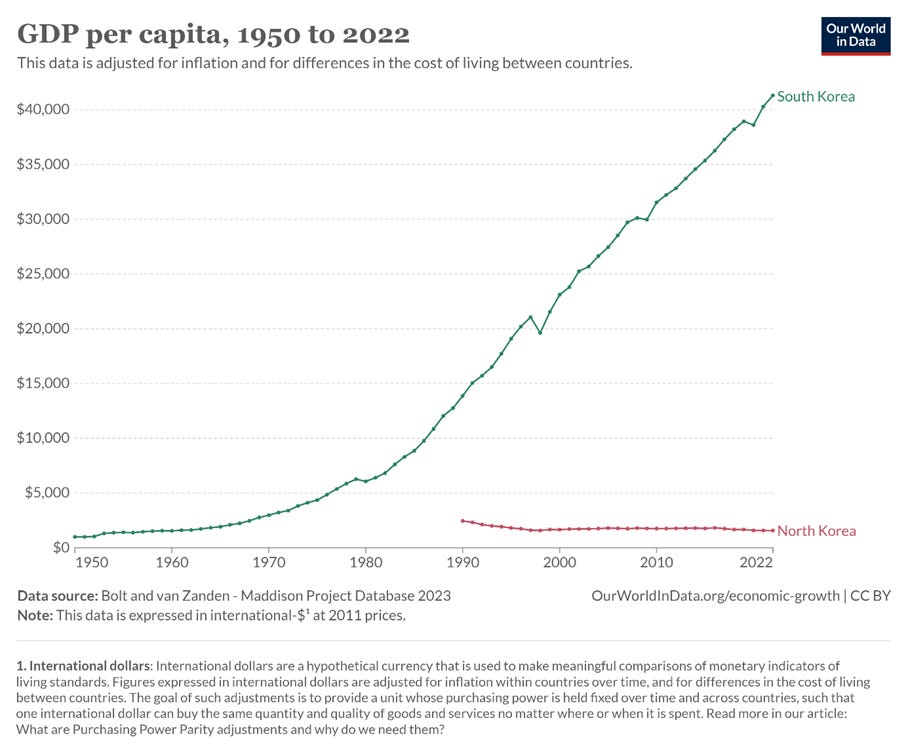

Korea

Korea was divided into North Korea and South Korea following the Korean War in 1953.

South Korea’s GDP per capita in 1953: $1,4695

North Korea’s GDP per capita in 1953: $1,469

South Korea’s GDP per capita in 2022: $41,3216 , an increase of 2713%

North Korea’s GDP per capita in 2022: $1,569, an increase of 6.81% (!)

This chart only began in 1990 for North Korea, but its real GDP per capita actually started at the same level as South Korea in 19507 .

Taiwan

Separated from China following the Chinese Civil War in 1950. Let’s also compare with Hong Kong, a British colony with Chinese culture until its return to China in 1997, then a Chinese territory governed according to the “one country, two systems” principle for good measure.

Taiwan’s GDP per capita in 1950: $1,4608

Hong Kong’s GDP per capita in 1950: $4,082

China’s GDP per capita in 1950: $799

Taiwan’s GDP per capita in 2022: $53,143, an increase of 3,540%

Hong Kong GDP per capita in 2022: $48,289, an increase of 1,083%

China’s GDP per capita in 2022: $19,238, an increase of 2,308%

Note how Hong Kong’s growth came to a screeching halt after the 2019 riots and the ensuing Chinese crackdown.

We will comment on China’s curve a little further down.

Singapore

Expelled from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, two years after joining, following a unanimous vote in parliament, making it the only country in the world to have become independent against its will.

Singapore’s GDP per capita in 1965: $3,9919

Malaysia’s GDP per capita in 1965: $2,876

Singapore’s GDP per capita in 2022: $80,320, an increase of 1,913%

Malaysia’s GDP per capita in 2022: $26,629, an increase of 826%

What do we learn from looking at these A/B tests?

We see countries that share the same history, culture, and language10 , and which were primarily divided by war (and independence against its will for Singapore).

And we also see major differences in wealth after a few decades. So what made the difference?

Many factors can be eliminated, or at least reduced, due to the relatively similar starting conditions.

Admittedly, there are geographical differences and starting conditions that sometimes diverge somewhat in economic terms, as can be seen in the initial GDP per capita.

But ultimately, what really made the difference were the systems of governance. In each case, one political and economic system clearly demonstrated its superiority over the “rival” system.

There is no doubt, for example, that if the North Korean government had administered the territory of South Korea, and vice versa, there would be a similar but reversed disparity between the two Koreas today: North Korea would be much richer than South Korea.

The wealth of data generated

Tests of this kind are extremely informative, as attentive observers can simply study the system that works better than the other and try to replicate it.

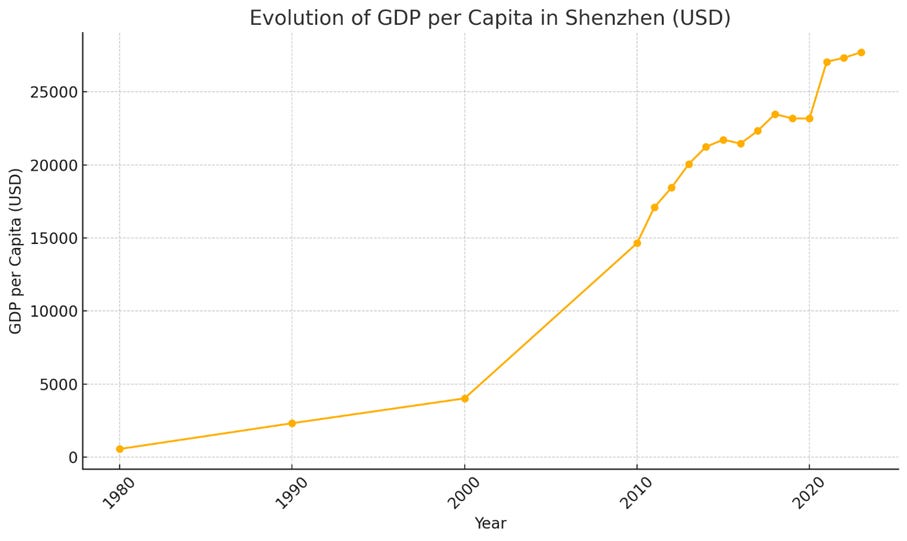

For example, it was after observing the success of Hong Kong that the Chinese government decided to set up a test economic zone in Shenzhen in the early 1980s11 .

The results were immediate12 :

Given Shenzhen’s considerable success, the Chinese government decided to liberalize its economy from the middle of the decade onwards, and especially from the early 1990s onwards13 .

Look again at the Chinese growth curve and note how, while it stagnated or grew slowly until that period, it began to rise sharply from the early 1990s onwards.

Without this experiment, which was then extended to the rest of the country, the current wealth gap between China on the one hand and Taiwan and Hong Kong on the other would be even more pronounced than it is today.

It has therefore been demonstrated that certain countries can take advantage of these tests to develop much faster than before.

However, these tests pose two major problems:

They were carried out against the will of the population in each case.

Such experiments have been too few and far between.

Now imagine that we could experiment with systems of governance, but without war, without revolution, without forcing a minority of people who do not want to be subjected to the tyranny of the majority.

And imagine that we could conduct not just a few tests here and there, but hundreds, thousands of tests.

A utopia?

Not at all. It already exists. But before explaining this new model of society, we must first talk about...

Coming soon

In the next article, we’ll take a look at how Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Romer proposed the concept of charter cities — experimental zones designed to test new governance models and help developing countries escape poverty.

Stay tuned! In the meantime, feel free to follow Disruptive Horizons on X/Twitter & Linkedin, and join the tribe of Intelligent Rebels by subscribing to the newsletter :

And here is the first articles in this series :

See Chapter 12 of The Way of the Intelligent Rebel for more details.

In 1990 dollars

“The two Germanies: Planning and capitalism - GDP per capita, 1950 to 1989,” Our World in Data

The diagram is taken from “The Eastern German Growth Trap: Structural Limits to Convergence?”, Ulrich Blum, Intereconomics, 2019.

“Institutions Matter: Real Per Capita GDP in North and South Korea,” Mark J. Perry, 2011. The figures given in this article have been adjusted to 2011 dollars.

“Bolt and van Zanden - Maddison Project Database 2023,” via Our World in Data.

See footnote 5 - “Institutions Matter: Real Per Capita GDP in North and South Korea,” op. cit.

See footnote 5 - Ibid. Figures are given in 2011 international dollars.

See footnote 5 - Ibid. Figures are given in 2011 international dollars.

For Singapore and Malaysia, it is a little more complicated, as Singapore has four official languages, including Malay, the language of Malaysia, which is also the national and historical language of the city-state. But English is the real lingua franca.

“China’s Special Economic Zones: Their Development and Prospects,” Clyde D. Stoltenberg, Far Eastern Survey, 1984.

This graph was constructed using data from “Shenzhen Statistical Yearbook,” 2024.

“A Political Economy of China’s Economic Transition in China’s Great Transformation,” Naughton, Barry, 2008

Such a good intro. If only charter cities were real! I’d love to see many metropolitan areas become charter cities and see what happens!

Couldn't agree more; the imperative to scientifically experiment with social models has never been more evident, especially considering how rapidly digital tools are resaping our collective structures.