A Ticking Time Bomb for Nation-States

Population Trends and Economic Peril

Note : After the 14-part series in which we looked at how nation-states are being disrupted by the Internet and globalization, here is the 4-part series on on why now is the worst time for them, of which this article is the 2nd :

At a time when nation-states are finding it increasingly difficult to control their tax levels, another problem is looming on the horizon: let's take a look at some data to see for ourselves.

Here is the evolution of the number of children per woman, from 1950 to 2021, for the world, Europe and the 3 largest English-speaking Western countries1 :

The number of children per woman fell :

From 3.45 in 1950 to 1.46 in 2021 in Canada, a drop of 58%.

From 2.24 in 1950 to 1.56 in 2021 in the United Kingdom, a drop of 30%.

From 2.93 in 1950 to 1.66 in 2021 in the United States, a drop of 43%.

From 2.70 in 1950 to 1.48 in 2021 in Europe, a drop of 45%.

And every other country in the world has also experienced this downward trend, without exception: the number of children per woman worldwide has fallen from 4.86 in 1950 to 2.32 in 2021, a drop of 52%.

Knowing that for a population to remain at the same level (without immigration), it needs to have 2.1 children per woman.

At the same time as the number of children per woman was falling, another indicator was rising: life expectancy at birth.

I stopped the data in 2019, because COVID temporarily distorts the results.

Here is the same data in table form2 :

The average age of the population is also rising:

And the same data in tabular form:

Fewer children, but people are living longer and the average population is therefore getting older: these trends have a direct impact on another important figure - the number of retirees in relation to the number of working people.

On this graph3 , you can see the evolution of the percentage of people over 64 (and therefore assumed to be retired), in relation to the working population (aged 15 to 64).

The higher this figure rises, the more each working person has to pay for a large number of pensioners: with a ratio of 10%, there is one pensioner for every 10 working people; with a ratio of 50%, there is one pensioner for every 2 working people - with all that this implies for the social contributions weighing on working people.

Here's the same data in tabular form:

In 1950 in the United States, for example, the ratio of retired people to the working population averaged just over 12%, or almost 8 working people for every retired person.

And in 2021, this figure will be around 25% retirees, i.e. around 4 working people for 1 retiree: each American working person in 2021 will therefore have to support twice as many retirees as in 1950.

And this figure, of course, is only getting worse: take a look at the curves in the diagram above, and those for the population of the continents below.

As you can see, on every continent apart from Africa, this curve is rising steeply: there are fewer and fewer working people per pensioner, and the trend is accelerating.

This exacerbates the competition between jurisdictions discussed in a previous article: the battle will not only be to attract talent, but also to attract young talent, or even young people at all.

Emigration of even a small percentage of a country's working population will greatly accentuate the problem of an ageing population and the number of retirees per working person.

This ratio also has a direct effect on the dynamism of economies and the ability of governments to raise taxes: fewer people working in an economy means less value generated, less growth, and less tax revenue.

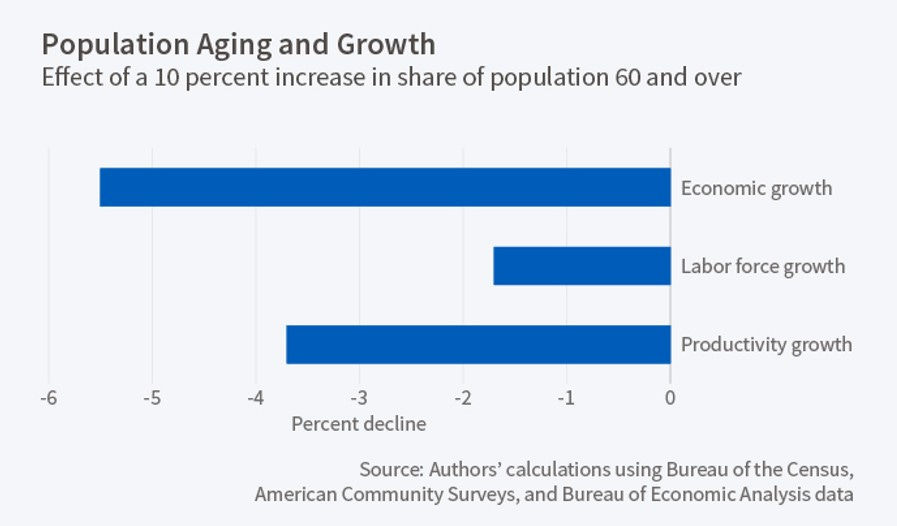

Researches4 shows that for every 10% increase in the proportion of the population aged 60 or over, we can expect economic growth to fall by just over 5% a year, labor force growth by just over 1%, and productivity growth by almost 4%.5

How to avoid a collapse of the pension system

The four main ways to avoid a collapse of the pension system (and a significant economic downturn) are therefore :

More children

Opening the immigration floodgates

Raising the retirement age

Raising taxes

On the subject of having more children, you can check out the curves I've shared above to see if this is a trend or not (spoiler alert: it's not a trend at all).

Opening the floodgates to immigration is an option, but one that poses numerous problems of integration for the new arrivals, and also a problem of competition: when everyone wants to attract immigrants, and Africa is the only continent with positive natural growth, what will the other countries do?

Who will be the winners and losers?

As for raising taxes, that's always a possibility, but 1) social contributions have risen sharply in recent decades as we saw in the last article, and 2) it goes against the general trend, that we also saw in the last article, in which governments find it difficult to raise taxes in an increasingly competitive world where jurisdictions are fighting to attract you.

And every tax increase also reduces the money available in the population for other things, which slows economic growth.

That leaves raising the retirement age: how do the countries concerned manage this?

Unfortunately, these data6 do not have a global average - fortunately, there is a European average - and start in 1970, but they are nonetheless very interesting.

I've added France and Belgium, as I'm writing my book in French, my mother tongue, and focused my initial research on French-speaking countries. The difference between the behavior of these two countries and that of other countries, particularly English-speaking countries, was sufficiently striking for me to say a few words about it below.

Here is the table:

As you can see, people are retiring earlier on average in 2018 than in 1970, even though there are far fewer working people per pensioner, and we live longer today than we did then...

In any case, this conclusion is true for most countries, but not for the USA, where apparently the population is pragmatic enough (and hard-working enough!) to understand that retiring early is no longer possible under these conditions, and who are retiring at roughly the same age as in 1970.

But even this is not enough: as we saw above, the number of retired people each working person has to support doubled in the United States between 1950 and 2021... and yet people are retiring at the same age!

I agree that we've had productivity gains thanks to technology since then, but still...

For the other countries it’s even worse : although the retirement age has begun to rise since the early 2000s, as the curves in the diagram show, the reforms remain insufficient.

Let's see how this affects social spending in the states concerned:

These data7 include all social spending - not just pensions - but give a good overview of their general evolution.

We have thus gone from an average of just under 9% social spending as a proportion of GDP in 1960, to just under 24% in 2016: a more than tripling of the burden on these states.

And what room for manoeuvre do governments have, given that this time bomb is arriving just as the Internet is disrupting their fundamentals?

As we'll see in the next article, the debt ratio of most states is so high that it's very, very narrow.

Stay tuned ! And in the meantime :

The other 3 articles in this series:

"World Population Prospects 2022, 27th edition", UNO

Life Expectancy, 1950-2019, Our World in Data

"World Population Prospects 2022", UN, via Our World in Data

"The Effect of Population Aging on Economic Growth, the Labor Force, and Productivity," Nicole Maestas, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016

"Population Aging and Economic Growth", National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016

"OECD Database on Average Effective Retirement Age" via Our World in Data

"OECD Social Expenditure Database (SOCX)", via Our World in Data

You’re forgetting another possible resource: letting youngsters work.

A century ago, a 15 year old person was ready to work, marry and become a useful citizen. In Western countries today, he or she is supposed to study for another decade before they can enter the labour market. Their energy, vitality and good ideas are wasted inside astonishingly old fashioned educational institutions. They learn to memorize details that can easily be found by the search engine of their phone, and to fake knowledge by presenting essays written by AI. What if they learned a trade while working, as they did in previous centuries?